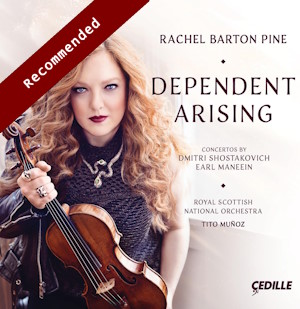

Dependent Arising

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Violin Concerto No 1 in A minor, Op 77 (1948)

Earl Maneein (b.1976)

Dependent Arising – Concerto for Violin and Orchestra (2017)

Rachel Barton Pine (violin)

Royal Scottish National Orchestra / Tito Muñoz

rec. 2022, Scotland’s Studio, Glasgow, UK

Cedille CDR90000223 [68]

Rachel Barton Pine is one of the few violinists whose new recordings I actively seek. This is because my experience shows that she allies supreme technical command to deeply insightful and intelligent musicianship. Along the way, her long term relationship with the label Cedille, nearing thirty years, has allowed her to build a discography full of unusual couplings and intriguing discoveries – even for the most avid collector. So it proves again here where Barton Pine takes arguably the greatest violin concerto of the 20th Century – Shostakovich’s Violin Concerto No 1 in A minor, Op 77 – and couples it with a work by a composer I have never heard of previously; Earl Maneein’s Dependent Arising – Concerto for Violin and Orchestra. With a work of the towering stature of the Shostakovich, other performers stick with more “logical” couplings such as Shostakovich’s second concerto or those by Britten, Khachaturian, Prokofiev, Barber, even Glazunov and Tchaikovsky to name a few. Only Violinist Eldbjørg Hemsing on BIS (a version I have not heard) opts for an equally unfamiliar work – in her case Hjalmar Borgström’s concerto from around 1914. So Barton Pine is challenging the listener with a bang up-to-date contemporary concerto which draws on her passion since childhood for Heavy Metal music. Consider for a moment that the Shostakovich written in the mid 1940’s remains the most recent ‘classical’ violin concerto to have entered the active repertoire of every virtuoso violinist – whether that is a comment on modern compositions or modern audiences I do not know. There have been many very fine violin works written since the Shostakovich, but none have achieved its ubiquity.

The listener is further challenged by the placement of the Shostakovich first on the disc giving the Maneein the unenviable position of “follow that…” Especially so given the circumstance that the Shostakovich receives an absolutely tremendous performance here, fully cementing its status of greatness. Barton Pine’s technical prowess is a given but what I admire so much here is her control of the big musical paragraphs. Rightly I think this work has been described as a “symphony-concerto” and certainly the opening numbed, emotionally bereft Nocturne occupies a similar expressive landscape to other symphonic works by Shostakovich of that period. However, there is a danger for players focussing on the considerable technical demands of sustained tone to rather lose sight of the musical direction or else rely on a ‘safe’ median dynamic. Barton Pine draws the listener inexorably through this twilight zone. In this she is significantly helped by the alert and sensitive playing of the Royal Scottish National Orchestra under the impressive baton of Tito Muñoz. The Cedille recording [producer James Ginsburg and engineer Hedd Morfett-Jones] is excellent too. From the very opening bars – and throughout the work – the remarkable individual brilliance of Shostakovich’s orchestration is richly apparent. Although recorded in standard CD format to my ear this is a demonstration-worthy recording of this concerto. Of course, the RSNO – or SNO as it then was – was the accompanying orchestra for the enduringly fine recording of the two Shostakovich violin concerti by Lydia Mordkovitch under Neeme Jarvi for Chandos. It is a measure of those performance’s stature, now thirty four years old, that they are still a bench mark. Another bench mark for both Shostakovich violin concerti must always be performances by David Oistrakh and any admirer of this composer’s music must know one of his performance’s. So high praise again to this new performance to be able to place it alongside those seminal performances.

After the moonscapes of the opening Nocturne, the nightmares continue in one of Shostakovich’s demonic Scherzi. Interesting to compare Barton Pine here with another favourite player – the magnificent James Ehnes – whose performance I reviewed a decade ago here. By stopwatch alone they are near identical – 6:23 – and both are technically superb so any critique of playing at this level seems almost petty, but Barton Pine somehow brings an additional sense of danger and threat whereas Ehnes is capricious. Other players have found that element of mania – Oistrakh in a BBC Classics live performance with Rozhdestvensky and the Philharmonia trading the last drop of technical polish for sheer rollercoaster excitement is a case in point. Other players – Mordkovitch with Jarvi or Sergey Dogadin with Alexander Sladkovsky conducting the Tatarstan National Symphony Orchestra on Melodiya (a genuinely excellent survey of all six concerti) opt for an earthier style which is also effective. But to my ear, Barton Pine seems ideal – the perfect blend of rapier-like virtuosity whilst also exploring the motivation behind the notes. Indeed, that sense of the best of both musical and technical worlds can be applied to the entire performance. The third movement is the powerful Passacaglia which again is notable in this new performance by the certain inexorable control of Barton Pine drawing the listener onwards with each repetition of the bass line towards the cathartic cadenza that links this movement to the closing Burlesque. One of the many demonstrations of Shostakovich’s especial genius was the way he so successfully combined the various roles of the cadenza in his concerti; virtuoso display, structural significance and emotional weight. The cadenza in his Cello Concerto No.1 fulfils a very similar role to the one in this violin concerto but I would suggest that this is his greatest achievement in the field. It represents a musical and technical culmination of what has come before with the technical display – which is ferocious – wholly at the service of the musical argument. Barton Pine crowns an already hugely impressive performance of the concerto to this point with an imperious and compelling performance of the cadenza.

In turn this leads without a break into a thrilling closing Burlesque. This is the movement which Oistrakh requested should start with an orchestral tutti, just to give him a chance to wipe his brow and catch his breath after the coruscating cadenza. Again, important to stress that there are many genuinely excellent performances in the catalogue but I do find Barton Pine wholly convincing, combining the best performing choices of bravura display with a kind of Cossack-dance energy. Muñoz and the ever excellent RSNO are likewise on the top of their game, all of which results in a performance worthy of standing alongside the most famous and best.

Composer Earl Maneein was born the year after Shostakovich died. His background is more as a performer/songwriter and he is the lead violinist for the guitar-less metalcore band Resolution15. He wrote a solo violin metal-inspired work for Barton Pine in 2014. Tito Muñoz was in the audience and from that performance sprung the idea of a full-blown metal-influenced concerto for same artists which was premiered by the Phoenix SO in April 2017. There is a brief rehearsal clip of that performance that can be viewed here that will give the listener a pretty good idea of the soundscape of the work. On a slight tangent, worth mentioning here the excellent liner note (a recurring feature of these Cedille releases) which includes a personal note by Rachel Barton Pine – articulate and insightful as ever, and the main extended English-only liner by Maneein where he writes about both concerti. Maneein’s liner is conversationally written and he avoids any kind of dry academic analysis but instead writes with an enthusiastic informality. Along the way the reader learns that Maneein is a conservatoire-trained violinist himself and indeed played the Shostakovich in competition – a competition he rather disarmingly admits to not winning! But what this does show is that he is a skilled and knowledgeable musician who just happens to prefer working in the rock/metal field rather than the traditional classical.

The benefit for the work he has produced is that this is not the kind of soft/pastiche rock orchestral work that too often blights attempts at cross-over. Do not listen to this work expecting an easy listen. This is a substantial 31:33 three-movement work that is a demanding, not easily accessible listen with a massively hard solo violin part that Barton Pine tears into with all her characteristic dynamism and high skill. The work’s title Dependent Arising draws on Maneein’s Buddhist faith, where there is a concept; “that all things arise in dependence upon other things. Nothing in the entire universe.. happens independently.” In the liner Maneein articulates passionately the aspects of his faith that he then finds a musical expression for. These are also bound up with his own experiences in life and as a performing musician which results in a work that is clearly deeply personal. The problem for a ‘new’ listener who shares few if any of those experiences or indeed any familiarity with the style of musical gesture (ie thrash metal) utilised is to find a aural pathway into the musical language used and/or the emotions that this language generates.

On one level I find myself massively impressed by the actual technical performance of all involved here but on another – even after several dedicated listens – I do not engage emotionally with this music at all. By his own admission, Maneein is not experienced with writing for a large orchestra and frankly that is what it sounds like. The result is too often large slabs of fairly undifferentiated orchestral texture where there is a distinct suspicion that material could have been swapped from – say – brass to wind groups with little or no impact except for a timbral shift. Maneein self-deprecatingly acknowledges the help given to him by both soloist, conductor and composer friend Raphael Fusco (“functioning as a de facto composition teacher”) during the work’s creation. Maneein displays a violin player’s understanding of the instrument by including a series of cadenza-like passages for solo instrument which sound brutally hard for lesser mortals than Barton Pine. Lack of familiarity again means that for the listener the “why” of these cadenzas’ placement and role is not immediately obvious. Compared to Shostakovich’s laser precision in the orchestration this new work does sound chaotically cluttered. Now of course, it can legitimately be argued that walls of epic sound are an important part of the heavy metal experience and I can imagine that this might well be a gateway into the world of Classical Music for Metal fans more than the other way around.

What is undoubtedly clear is the complete dedication and belief of the performers which means that even for an as-yet-unconvinced listener such as myself, you can be certain that the work is being presented in its best possible light. The playing of the RSNO is alert and incisive and the Cedille engineering allows as much detail to register as the over-scored writing allows. The engineers also manage a clever aural sleight-of-hand whereby Barton Pine’s violin is immersed in but not swamped by the orchestral writing. As I wrote at the start of this review, Rachel Barton Pine is a musician and violinist whom I implicitly trust and respect. She clearly knows this work far better than I ever will, so I will continue to listen to this work beyond my reviewing remit. A Shostakovich concerto for the ages, perhaps the Maneein will prove to be given time, perhaps not.

Nick Barnard

Help us financially by purchasing from