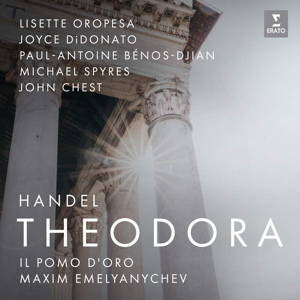

George Frideric Handel (1685-1759)

Theodora, HWV68 (1750)

Lisette Oropesa (Theodora) – soprano

Joyce DiDonato (Irene) – mezzo-soprano

Paul-Antoine Bénos-Djian (Didymus) – counter-tenor

Michael Spyres (Septimius) – tenor

John Chest (Valens) – baritone

Massimo Lombardi (Messenger) – tenor

Il Pomo d’Oro/Maxim Emelyanychev

rec. 2021, Alfried Krupp Saal, Philharmonie Essen

Libretto included

ERATO 5419717791 [3 CDs: 178]

Famously, Theodora was the least-performed of Handel’s oratorios during his lifetime. Its subject of virtue, and fidelity to Christian faith, was unusual subject matter for him but it was a product of his maturity, written when Handel was 64, and brought from him music of penetrating but often deliberately muted depth. It deserves a performance that matches its singularity of purpose and that unremitting sense of faith.

What it receives here is high drama and inconsistency: inconsistency of casting and of expressive tone. There’s no doubting the zest and commitment of Il Pomo d’Oro and their harpsichordist-director Maxim Emelyanychev, who have staked out a strong place in Baroque repertory on disc and in concert. Right from the Overture their restless playing – the bass line especially – points up the underlying tensions to come, and that are anticipated in this brief though combustible orchestral overture. However, the initial harpsichord and continuo flourish into the opening recit also suggests an extravagance that can sound self-regarding, and not musically focused. There is, in fact, and throughout, a punchy and almost belligerent orchestral tapestry that militates against the more spiritual and transcendent aspects of the work.

This is exemplified in the casting. The aptly named baritone John Chest takes the role of Valens. He’s an American from South Carolina but to my ears his accents and articulation are tight and rather Germanic. Compare and contrast his First Act standout aria ‘Racks, gibbets, sword and fire’ with that of Christopher Purves on a Handel arias disc for Hyperion: Purves has significantly more personality and tonal presence. As Didymus there is the counter-tenor Paul-Antoine Bénos-Djian, serviceable and with good control of divisions. His is a rather masculine sounding assumption, not inappropriately, but the voice itself is nothing special. Septimus is taken by Michael Spyres, who seems to be something of a flavour of the month. What a strange impression he leaves, though. His downward runs sound odd and his voice is inclined to tighten which means articulation and colour engage in a kind of vocal civil war – listen to ‘Descend, kind pity’. Elsewhere his coloratura is agile enough, but he tends to bark, disrupting the line in ‘Dread the fruits of Christian folly’ and he croons through the divisions of his Act III aria ‘From virtue springs each gen’rous deed’, skimming the line not hitting it with rhythmic accuracy; beefily superficial, stylistically inappropriate.

The most consistent and best singing comes from the two women, though with reservations. Theodora is Lisette Oropesa and she sings with directness and without some of the frailties and eccentricities that afflict some of her fellow cast members. Irene is sung by Joyce DiDonato, who uses her skill to colour and fire her aria ‘Bane of virtue’ with necessary anger. Irene has some of the best music and ‘As with rosy steps the morn’ is amongst the most moving, and affecting, of them all, an aria I always associate with Lorraine Hunt Lieberson. Though she sings it well, DiDonato over-decorates in the da capo and can’t match Hunt Lieberson’s sheer nobility of utterance; no one can, really. And where she truly disappoints is in excess. Act III’s ‘Lord to thee each night and day’, whilst graced with fine coloratura, seems to me then to descend into soloistic preening. If this was encouraged by the conductor, it’s to be regretted.

The choir is well drilled though it reflects the erratic emotional temperature established by Emelyanychev. The final chorus of Act I, ‘Go gen’rous, pious youth’ is suitably measured but ‘He saw the lovely youth’ which ends Act II is, by contrast, incongruously fast. ‘How strange their ends’ is taken at a jog-trot tempo. The orchestra is colourful, the oboes in particular, but – and this reflects the director’s own preference – is inclined to be too interventionist.

That it’s well recorded can be taken as a given and there is a libretto with notes. However, this adds up to a recording significantly less than the sum of its parts and presents a partial view of Theodora. Youthful, impetuous and dramatic it may be, but stoicism, gravity and consolation are in shorter supply. For those qualities I’ll stick with Paul McCreesh on Archiv.

Jonathan Woolf

Help us financially by purchasing from