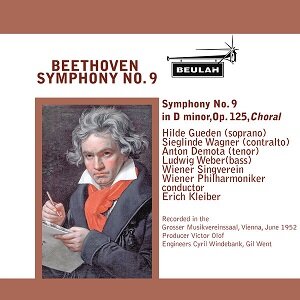

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Symphony No.9 in D minor Op125 ‘Choral’

Hilde Gueden (soprano) Sieglinde Wagner (contralto) Anton Dermota (tenor) Ludwig Weber (bass) Wiener Singverein

Wiener Phiharmoniker/Erich Kleiber

rec. June 1952, Grosser Musikvereinssaal, Vienna

Reviewed as a digital download from a press preview

Beulah 1PDR83 [66]

One of the great what ifs of conducting concerns what might have happened if Erich Kleiber had lived on to the ripe old age of a Klemperer or a Karajan. His post-war recordings give a tantalising glimpse of a career that would certainly have rivalled those two big names. This new restoration by Beulah affords us such a perspective on what might have been and the view it provides is of a very modern performance indeed.

Right from the first bars, it is clear that Kleiber’s is a tough, uncompromising vision of the opening movement. Whilst Kleiber still takes a minute longer than my preferred period choice in this movement, Pablo Heras-Casado, this is very brisk for the era. He certainly believes in pushing the Vienna Philharmonic very hard – probably much harder than they were used to this work. Kleiber is brutal and unbending in the way he drives the music on. It is very exciting and the mellowness of the sonorities of the VPO save it from sounding too severe. It is abundantly clear that that most recalcitrant of ensembles really wanted to play for him. Kleiber’s brusqueness leaves no room for mystery – the opening rather than emerging out of a haze of cosmic dust is clear and precise. The coda is similarly clear eyed and works up to tremendous resolution.

Having cracked the whip in the first movement, Kleiber can afford to let things relax a little. Kleiber is very keen to stress that this is in triple time which he achieves with a fractionally slower tempo. Kleiber doesn’t have any big interpretative points to make. He is mostly interested in ensuring that textures are clear and dynamic and that the music is articulated cleanly and with suitable energy. I told you this was a performance very much ahead of its time! Even the trio, if nowhere near the gabble that ensues if the metronome marking is followed accurately as it seemingly must be these days, is much brisker than would have been usual for 1952.

In the slow movement movement, whilst on the quick side compared to Furtwängler, and comparable to Karajan in his first Berlin cycle, Kleiber is slower than Toscanini and a whopping 4 minutes slower than Pablo Heras-Casado who might now hold the land speed record for this movement. Toscanini at least makes sense of his fast speed – something, for all his efforts Heras-Casado just can’t do. Kleiber, with a characteristic minimum of fuss chooses a sensible adagio molto speed and in doing so gives himself plenty of room for a nicely flowing alternating andante moderato. Once again, the VPO are on their best behaviour for Kleiber and play with great beauty in a way again surprisingly free of mannerisms. Only in the big climax toward the end of the movement did I long for some of Furtwängler’s visionary magic. Furtwängler was always outrageously slow but who cares when he can take the listener to the stars? If Kleiber was temperamentally incapable of such indulgence, his is a version of great nobility of spirit and his shaping of Beethoven’s long melodies reflects an expert opera conductor and coacher of singers.

This makes the Achilles heel of this recording – the choral singing – all the more unfortunate. Decca have assembled a very starry roster of solo singers but have got rather lumbered with Karajan’s favourite choir. The politest thing that can be said about them is that they are as soft focused as they ever were for das Wunder Karajan. Presumably aware of the severe limitations of his chorus, Kleiber chooses some uncharacteristically conservative tempi. I don’t believe for a second based on the opening two movements alone, that Kleiber would have chosen such modest speeds if he had access to a better choir. As it is, it is a serious blot on an otherwise exceptionally fine Choral Symphony.

Things get off to a rousing start with Kleiber shaping the big tune with aplomb and building the excitement leading to the entry of the voices excitingly. Things unfortunately get a little more staid with the arrival of the chorus. Kleiber rules them with a rod of iron but they are too often frankly all over the place with sloppy ensemble and clearly a significant number of the sopranos who can’t or can’t be bothered to sing Beethoven’s taxing top notes. I won’t go on further as things don’t improve as the music gets more demanding.

Turning to the soloists, Weber is predictably superb and the ladies acquit themselves respectably. Anton Dermota, who only a few years before had delivered a Tamino for the ages for Karajan, sounds like a singer in decline with the irresistible sweetness of his voice now sounding pinched and effortful.

Beulah have done a sterling job of brightening the sound compared to the most recent Decca reissue which, particularly in the opening movement, gives the sound real punch. I’m unsure whether clearer sound does the Wiener Singverein any favours but the orchestra sound glorious.

An imperfect recording then but an important one given that Kleiber’s death robbed us of hearing more of his Beethoven. If he had lived longer, I’m sure he would have gone on to produce a stereo remake with a better choir. As it is, Kleiber’s conception is deeply compelling and few conductors have got as much out of the Vienna Philharmonic.

David McDade

Availability: qobuz