Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

The Voyevoda, Op 78 (1890-1891)

La Tempête, Op 18 (1871, rev. 1888)

Overture and Polonaise from Cherevichi (1885)

Francesca da Rimini, Op 31 (1876)

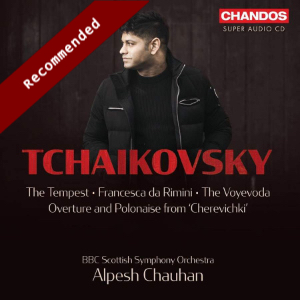

BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra / Alpesh Chauhan

rec. 2022, City Halls, Glasgow, Scotland

Chandos CHSA5300 SACD [78]

The Birmingham-born conductor, Alpesh Chauhan cut his teeth as Assistant Conductor of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra (2014-16). Towards the end of his time in that post I recall seeing him conduct Shostakovich’s Fifteenth Symphony in an excellent concert (review). Since then, his career has taken him to orchestral posts in Parma and Dusseldorf, and he has retained his Birmingham links as Music Director of Birmingham Opera Company. He’s also Associate Conductor of the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra and I think I’m right in saying that this disc is their recording debut together. Chauhan has chosen a most interesting programme of works by Tchaikovsky, placing the focus on some of the composer’s pieces which aren’t quite as frequently performed as they deserve to be.

Proceedings open with the last of Tchaikovsky’s programmatic orchestral works, The Voyevoda. This Symphonic Ballad was inspired by a poem, ‘The Ambush’ by the Polish poet, Adam Mickiewicz (1798 – 1855), which, David Nice tells us in his notes, Tchaikovsky read in a Russian translation by Pushkin. In brief, a local lord (or voyevoda) returns home from military service to find his wife dallying in the garden with a young man. The voyevoda, believing his wife to be unfaithful, orders his servant to shoot her. However, the servant shoots his master instead. Quite what happens after that is unclear because Tchaikovsky brings the work to a rather abrupt end after the voyevoda’s demise.

This Symphonic Ballad is not, I think, quite on a par with works such as Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet or Francesca da Rimini. However, it’s a far from negligible score and the orchestration is full of interest. Tchaikovsky makes good use of the harp and there’s also an important part for the celeste. I must confess I had thought that the instrument made its debut in The Nutcracker (1892) but David Nice points out that, having heard the instrument in Paris, Tchaikovsky was impatient to use it in his music and so used it first in The Voyevoda. In this performance Chauhan and the BBCSSO depict the voyevoda’s ride home excitingly; the performance is finely detailed, especially in quieter passages. The love music occupies the central position in which Tchaikovsky habitually placed it in the structure of pieces such as this. It’s briefer than in some of his comparable orchestral works but it still makes a good impression and it’s lavishly decorated. The death of the voyevoda (11:35) is graphically depicted but then, after a doom-laden episode for the low brass. Tchaikovsky ends the work rather abruptly. Chauhan and the BBCSSO make a strong case for The Voyevoda.

Next up is a much earlier piece, La Tempête, which originally dates from 1871; it was then revised in 1888. The piece, inspired by Shakespeare’s play, was composed shortly after the much more famous Romeo and Juliet Fantasy-Overture (1869, revised 1870 and 1880). La Tempête may not be quite as memorable as Romeo and Juliet but when heard in as fine a performance as the present one, it seems unfairly overshadowed. It opens with a highly imaginative and very atmospheric seascape which leads David Nice to pose the very fair question: where did that come from? There’s nothing, so far as I know, that’s comparable in Tchaikovsky’s previous output. Chauhan and his players depict the gently swelling seas very successfully. In the music that follows, which focuses on Prospero and his spells, we are treated to red-blooded playing. The love music for Ferdinand and Miranda moves from tender, innocent beginnings through to ardent passion. I really like the gossamer lightness of the playing in the brief episode that depicts Ariel. Towards the end, Tchaikovsky offers a full-bodied reprise of the love music, but then, in a stroke of genius, he resists the temptation to go for a crowd-pleasing, passionate Big Finish; instead, he pulls a compositional rabbit out of the hat and closes the piece with a return to the opening seascape. That’s a gesture I find very satisfying. The performance by Chauhan and the BBCSSO is compelling in every respect.

A little light relief is provided through the two excerpts from the Comic-fantastic Opera Cherevichi (‘The Slippers’). Though I use the term light relief, that’s relative to the high drama of the three main orchestral works; the music in these two operatic excerpts is high-quality. The Overture is both attractive and varied, Chauhan leads a sparkling performance in which attention to detail is very evident. The Polonaise, which in David Nice’s words, “represents the pomp of the imperial court”, is given a colourful and most enjoyable performance.

The programme ends with the Symphonic Fantasia after Dante, Francesca da Rimini. I’ve long thought that this is a terrific work and I wish we heard it more often in the concert hall. That we do not may be due to the challenges it presents to the orchestra, though you wouldn’t guess that from hearing the BBCSSO play it. Tchaikovsky took his inspiration from Canto V of Dante’s Divine Comedy: Chandos actually include the Italian text of the relevant passage, and an English translation, in their booklet.

There’s much to admire and relish about Chauhan’s performance, which Chandos helpfully divide into four tracks. The Andante lugubre opening is powerful and full of foreboding. Then the Allegro vivo section – and even more so its reprise at the end of the piece – is fiery and exciting. I’m a little thoughtful about the way that Chauhan plays the extensive central section – love music again! The main marking is Andante cantabile non troppo and I’m not entirely sure he takes sufficient notice of the ‘non troppo’ qualification. I compared his performance with the 1969 account from Barbirolli and the New Philharmonia (Dutton/Barbirolli Society CDSJB 1019) and the famous account recorded in 1958 by Stokowski with the pseudonymous Stadium Symphony Orchestra of New York (in reality, the New York Philharmonic, I believe). Both of these conductors start the section expansively, as does Chauhan, but after a while both of them modify the tempo, moving it on with greater flow. Chauhan is consistently steady and, it’s important to note that he thereby obeys Tchaikovsky’s injunction L’istesso tempo. Stokowski in particular presses forward – though not excessively – from 10:52 in his recording. Chauhan’s account of the episode is lovingly done and the playing of the BBCSSO is very persuasive. I just feel that a slightly more forward-moving tempo in this extended episode would have convinced me even more. As it is, his account of the work overall is a very fine one, even if it doesn’t quite surpass Stokowski’s performance, which is simply superb; Stoki’s way with the concluding Allegro vivo is absolutely electrifying, especially from 22:54.

One small subjective reservation about Francesca da Rimini – which other listeners may not share – doesn’t detract from the overall verdict that this is a terrific Tchaikovsky disc. Alpesh Chauhan clearly has a feel for this music and he conducts it really well; I’d love to hear him in either Hamlet or Manfred – or, even better, in both. The BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, guided by a succession of notable Chief Conductors – Osmo Vänskä, Ilon Volkov and Sir Donald Runnicles – has been attracting critical plaudits for a good number of years now and these performances demonstrate why. Collectively, they are on top form and I admired not just the skill they bring to these performances but also the degree of commitment.

The quality of the playing is shown in the best possible light by the outstanding Chandos sound. These recordings pack a real punch and the music-making registers with maximum impact. There’s also a wide dynamic range, which brings out the attention to detail which Chauhan and the players bring to the performances. The sound has great realism; sample, for instance, the way that during Francesca da Rimini the tam-tam is reported at a variety of dynamic levels, including one spectacular crash (track 10, 2:19). I applaud Chandos for dividing all three of the major works into a number of tracks; that’s most helpful. To complete the high standards of presentation, David Nice’s notes are valuable.

As I said, I believe this is the recording debut of Alpesh Chauhan and the BBCSSO. It’s an auspicious debut: more, please!

John Quinn

Previous review: Ralph Moore (July 2023)

Help us financially by purchasing from