Déjà Review: this review was first published in July 2005 and the recording is still available.

Richard Wagner (1813-1883)

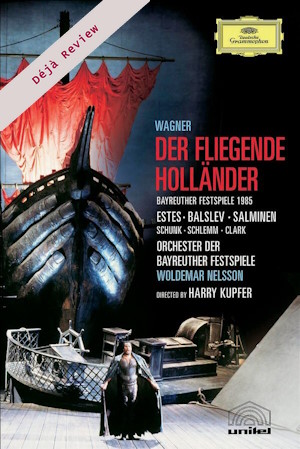

Der fliegende Holländer

Daland: Matti Salminen, Senta: Lisbeth Balslev, Erik: Robert Schunk, Mary: Amy Schlemm, Der Steuermann Dalands: Graham Clark, Der Holländer: Simon Estes

Chor der Bayreuther Festspiele/Robert Balatsch,

Orchester der Bayreuther Festspiele/Woldemar Nelsson

rec. 1985, Bayreuth

Director: Harry Kupfer

DVD-all regions; 5.1 DTS surround sound.

Deutsche Grammophon 073 4041 DVD [135]

When I was young, my father said: Don’t judge others before hearing them through, listen before interrupting. His advice applies so well to Wagnerian opera, with its potential for diverse interpretation. The greatest works of art have the power to speak beyond restricted parameters of space and time. We may have a preference for one style or another, but when we listen to a new production, it’s a good idea to listen to it for what it conveys on its own terms. Whether we like or dislike something isn’t ultimately the point, for we learn something along the way.

This Bayreuth production sets Der fliegende Holländer in Wagner’s own time. What it loses from the usual quaint folkloric setting it gains from a more direct connection to the social and moral issues that influenced the composer. It’s a cerebral production. The Weberian fantasy elements are downplayed, but the links to later Wagner are clearer. From the very start, Senta is in full focus. Lisbeth Balslev portrays her as a nineteenth century old maid, well past the first flush of youth and most decidedly neurotic, clutching the Holländer’s portrait and moving with trance-like stupor. It’s almost a relief to return to “reality” with Salminen’s hearty Daland and Clark’s particularly well characterised Steuermann. But Senta’s pinched, anxious features are still there – she’s on stage, above the action. Then in a spectacular tour de force of stage craft, the ghost ship sails head on into the stage. The bow opens, to show the Holländer, chained in its maw like Prometheus. Simon Estes is superb: the power of his voice and the magnetism of his body language are, frankly, erotic. He’s no pallid ghost, he exudes sensual energy. Senta’s obssession is clearly sexual. Is she a prototype Isolde, for whom repression connects love with punishment? It’s interesting to observe her reactions as she listens to her father offer her to the stranger, Wagner set their “dialogue” as an interesting cross-current, two contrasting monologues. Salminen and Estes both equally powerful, underline the inherent tension.

Bizarrely, the women in the Second Act are again dressed in formal bombazine, images of middle class propriety. Some of them aren’t even spinning, but drinking tea from porcelain cups. They sing cheerfully enough, but it emphasizes the fact that their chorus praises marriage as a business transaction – girls spin, men bring gold, and that’s how society works. So Senta is breaking two taboos, one with conventional society and the other with the devil himself, by offering herself to break his contract with the Holländer. No Wagnerian heroine chooses convention when she can do something of cosmic import. Defeating Satan is a greater challenge than marrying Erik, however worthily performed by Robert Schunk. No wonder Wagner was able to persuade comfortably married women to give up their lives for him. But there’s no mistaking what fascinates Senta here, for Estes projects an almost hypnotic sensuality. He is wonderful, singing with smouldering passion, almost carrying the opera by himself.

The crowd scenes Wagner was to perfect in Meistersinger, play an important part in Der fliegende Holländer, for they contrast the iconoclastic self absorption of the principals with the rest of the world, so to speak. Unlike some productions, the chorus scenes here have a carefully choreographed quality. Guests at the feast promenade in top hats, and bow. Even when the storm strikes, the sailors move in almost balletic turbulence. The singing is precise, if not altogether clear, but that only enhances the excellence of Clark’s interjections as Steuermann. In musical and textual terms, this is extremely effective. There’s even an allusion to Meistersinger at the end, when the shutters of the town windows suddenly snap shut. The orchestral playing is competent if unobtrusive, supporting the singing rather than stirring it on.

This is definitely a thought-provoking interpretation. I’m not sure that the portrayal of Senta as insane is one I’d want to follow too often, but it is valid in this context and certainly more interesting than productions which treat her as a brainless cypher who suddenly finds nobility in self-sacrifice. Nonetheless it is an intriguing proposition. It does illustrate, to borrow a phrase out of turn “Wahn, Wahn, überall Wahn”, Wagner’s most fundamental belief that the complexities of human nature are beyond simple classification. In this, he heralded the whole idea of psychodrama. This production thus connects this early opera with the others to follow. It won’t perhaps appeal to those who like a Flying Dutchman redolent of Der Freischütz, complete with dancing peasants. But those who like Wagner on an intellectual level will enjoy this.

Anne Ozorio

Help us financially by purchasing from