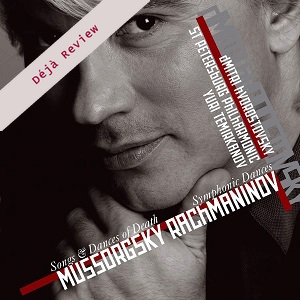

Déjà Review: this review was first published in July 2005 and the recording is still available. Dmitri Hvorostovsky passed away in 2017.

Modest Mussorgsky (1839-1881)

Songs and Dances of Death (1877, orch. 1962, Dmitri Shostakovich)

Sergey Rachmaninov (1873-1943)

Symphonic Dances (1941)

Dmitri Hvorostovsky (baritone)

St Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra/Yuri Temirkanov

rec. live, 24 August 2004, Royal Albert Hall, London

Warner Classics 2564 62050-2 [54]

Mussorgsky wrote the first three of these songs in 1875, the year after Boris Godunov was first performed, and The Field Marshal in 1877. According to Andrew Huth’s liner-notes he had plans for a longer song cycle, “perhaps as many as twelve”, but since death intervened, these four are all we have. And fascinating they are, dramatic and still sounding quite modern. We don’t know if the composer had any plans to orchestrate them, but his two friends and “faithful” partisans, Glazunov and Rimsky-Korsakov, provided an orchestration of the piano accompaniment soon after his premature death at the age of forty-two. As with other arrangements and revisions from his friends, they have had their detractors, so in 1962 Shostakovich made his own adaptation, which has won universal acclaim. There are others also. Kim Borg recorded the cycle for Supraphon in the 1960s with an arrangement “specially prepared for this recording”. It doesn’t say by whom; a guess is that it might be Borg himself who also was a skilled composer. The songs require a deep male voice with histrionic power and that is what Kim Borg had in abundance. His was also one of those warm, rounded bass baritones that could sing with melting beauty. Hvorostovsky reminds me of Borg, although his is a pure baritone. He has the beauty, roundness and timbre that is quite reminiscent of Borg’s. Hvorostovsky also recorded this cycle at the beginning of his career, in January 1993 for Philips with the Kirov Orchestra under Gergiev. That too involved the Shostakovich arrangement. A comparison shows that even then he was an eloquent interpreter. His voice was a little brighter, a little lighter; on the present recording it has naturally filled out, but not much. It is still that wonderfully sonorous instrument out of which pours a stream of golden tone. Interpretatively, the differences are not that big. If anything, he is more detailed, more lieder-like in his utterances in the early recording. He has always been good with the words, and he never misses an opportunity to inflect a phrase, to underline the emotion. In the more recent version he is still very keen with his words, but it is also a big-boned and grander performance. That might have something to do with the occasion. In 1993, he recorded in a studio in St Petersburg; in 2004 he was on stage, live, at a Proms concert in the Royal Albert Hall. It seems natural that you project your voice in relation to the venue. Add to this an enthusiastic audience, of which we hear very little until the last song is over, when there is a lot of “bravo”-ing. I can’t really say that I prefer one version to the other; they are both excellent. Any lover of these songs would be fully satisfied with either – or both. This is also a matter of couplings. The Philips disc has a recital of Russian baritone arias, most of them not often heard and so a valuable addition to any collection of Russian opera.

The present Warner disc gives us Rachmaninov’s Symphonic Dances, his last composition and to my mind one of his greatest. It was first performed on January 3, 1941 by Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra, who also are the dedicatees. In a letter to Ormandy in August 1940, Rachmaninov wrote about his new composition which was then finished. He was about to begin the orchestration. At this stage the title was “Fantastic Dances”, but I think it was wise to make the change; they are truly symphonic. The first and last movements are both three-part structures, while the middle movement is a waltz. At first Rachmaninov had intended to entitle the movements “Noon”, “Twilight” and “Midnight”, a thought he probably abandoned when he changed the title of the composition. This work is definitely on a par with his second symphony and this third piano concerto, and in all fairness it should be played and recorded just as often as the two earlier masterpieces. Maybe the original title would have been more tempting.

The first movement, after an energetic opening section, contains one of his noblest melodies, played first (at 3:25) by an alto saxophone. The instrument that was new to Rachmaninov, who even consulted his friend Robert Russell Bennett about how to use it. At 5:20 the strings take over the melody; this is the true Romantic Rachmaninov sound, but without the sentimentality of “Full moon and empty arms”. The waltz movement is almost Tchaikovskian in its surge, but has more macabre undertones. The finale is a real tour de force for a virtuoso orchestra with an especially triumphant ending. Played here by one of the great orchestras under a conductor who has been their principal since 1988, the composition is presented in the best possible light. The strings are warm and silken, the wind has bite and the climaxes are thrilling. Tempos are well judged and the waltz has that hard-to-describe lilt; something a good performance of a Strauss waltz should also have.

This is a highly recommendable version. “But?” I hear a reader saying, inquiring. Well, were it not for the existence of another recording, much older, there wouldn’t be a “but”. As it happens though, the piece was recorded almost thirty-five years ago by the dedicatees, Ormandy and The Philadelphians for CBS. This, in its turn, was thirty years after the first performance and by then there wouldn’t have been many players left from that occasion. Ormandy was still there and the tradition was obviously deeply rooted in the orchestra. They play the music at white heat, with a precision that is even greater than the Russians, with a string sound that is not necessarily warmer but leaner. The rhythms have even more spring and the finale whirls along like a lava stream, leaving this listener breathless. It is not so much a question of tempo, for the playing time of this last movement is just half a minute shorter with Ormandy – it is a matter of lightness. Again the recording venue is to blame, for the Royal Albert Hall creates a more fleshy sound with its enormous volume. Once again this is an example of the outstanding being the enemy of the very good, for Temirkanov’s version is indeed very good. Without the knowledge of the Ormandy, which I have had around since the 1970s, I wouldn’t have had any reservations at all.

As it is we have here two excellent performances, and anyone who wants this particular coupling need not hesitate.

Göran Forsling

Help us financially by purchasing from