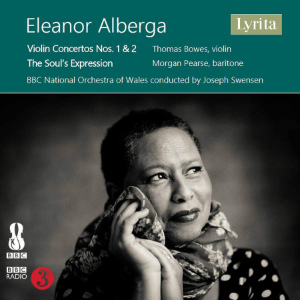

Eleanor Alberga (b. 1949)

Violin Concerto No. 1 (2001)

The Soul’s Expression for baritone and string orchestra (2017)

Violin Concerto No. 2 Narcissus – A Perfect Fool in one movement (2020)

Thomas Bowes (violin)

Morgan Pearse (baritone)

BBC National Orchestra of Wales/Joseph Swensen

rec. 2021, Cardiff, Wales.

Lyrita SRCD405 [75]

Eleanor Alberga, who was born in Kingston, Jamaica has centred her career in London. She was a student at the Royal Academy of Music – of which she is now a Fellow – and later progressed as a concert pianist – a course on which she was set from an early age. She also had a spell as pianist with London Contemporary Dance Theatre. Able now to focus on her heart’s desire as a composer, this disc is quite a landmark. Her other works include a trumpet concerto, piano solos, three string quartets and much else besides. Completed last year (2022), there is also a 30-minute symphony Strata, written for, and premiered by, orchestras in Bristol and Edinburgh.

The Soul’s Expression is for baritone and string orchestra (2017) and is blessed with Morgan Pearse’s steady voice. He carries the inflection of intelligent communication and puts across the meaning of words without compromising technique. He speaks to the listener’s mind as does Wilfred Brown in the famous EMI recording of Finzi’s so-movingDies Natalis. His voice evinces a sturdiness and unshakeable quality. He also acts the words and conveys that sense of fear teetering over into panic that you hear in Brian Rayner Cook’s classic broadcast of Havergal Brian’s’ Fifth Symphony Wine of Summer. There’s the same subtext in Edward Thomas’s words as ‘lofted’ by Pamela Harrison in the cycle for tenor and strings The Dark Forest. The selected poems in Alberga’s case are George Eliot’s Blue Wings and Roses and Emily Brontë’s The Sun Has Set. The cycle concludes with Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s The soul’s expression where Browning and Alberga have the listener in their “checkless griff”. This latter forces a descent into a chasm that is simultaneously fearful and inescapably reassuring.

The soloist for the violin concertos is Thomas Bowes. He plays most beautifully and with every sign and stamp of mastery. The Second Concerto Narcissus conveys a picaresque yet inward adventure. It does this in three tracks across just over twenty minutes. The inwardness – almost solipsistic – fits the self-reflecting Narcissus link. The music presents in a warm immersive tidal wash. There is a Prokofiev-like trudge about things in track 2. Our hero is determined but not a braggart. The alla Marcia effect we hear dimly resembles Bartók in the Concerto for Orchestra. Also, I could not help remembering a discovery I have made in the realms of film music: that is Jerry Goldsmith’s Islands in The Stream (Hemingway). Here the dream lulls, blandishes and disturbs. It serves as both a prelude to sleep and an invocation to action. In the last section, the music twists and turns and yelps with the violin taking on a dark and curdled texture unravelling into a disturbed silence.

The First Concerto is a big work (c36 minutes) in three movements. This opens in what amounts to a long tale that conjures a lambent ecstasy from the soloist. There is some tough writing here – the sort of wild caprice that we recall from the final section of the wild wood. The effect of the soloist in tumult is of a careering hay-wain on a mountain precipitous road that is just barely wide enough for the tottering wheels. The imminence of disaster seems to be the message. Bowes is almost subsumed in the heaving quicksilver lava; just like the groaning-moaning fake-dinosaur in Herrmann’s music for Journey to the Centre of the Earth. The second movement whispers in a platinum silver piano-pianissimo. Thoughts flow like mercury. The orchestra hums and chirrs in the background. The room subsides into silence as the composer confides her secrets. The finale exudes vigour and sprints away from silence amid slowly curling smoke, flying spume and spindrift. The orchestral piano takes a couple of steps forward and the movement ends in an almost Rimskian explosion at 7:10. The effect is of a wild whirl with none of the psychological complexities that thread through the start of the first movement.

Swensen is a fitting choice as conductor. Himself no mean violinist – he has recorded for Linn (review) and RCA – he can be relied upon to show sensitivity to Bowes – a fellow violinist – and does. On that front, the leader of the orchestra, Lesley Hatfield, has a long-time history as a soloist memorable for her Glazunov and RVW.

You can also rely on Paul Conway, much associated with Lyrita, to limn in the detail for music that will probably be new to most listeners. So it proves with this Alberga disc of works from the last ten years. His eight pages of notes dig and delve, reward and enthuse. The work of this composer falls into one of his major constituencies of interest. He writes about her with a solid base of information that is evident from core and context.

The words of all four poems used in the song cycle are set out very legibly in the booklet which is in English only. The sound is resplendent. The liner booklet plays its part in documenting recent history and tells us that the disc was recorded ‘Under UK COVID restrictions’.

A landmark in Alberga’s discography which, in large and as yet unfulfilled part, lies in the future.

Rob Barnett

Help us financially by purchasing from