by Charles A Hooey

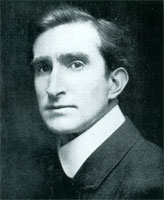

There once was an impresario known as Ernst, and another named Tom. They shared the same dream, had the same focus and both thought opera should become part of the British scene, perhaps even that citizens should hum arias now and then! No easy task, then or now. Each managed great things but they shared a common fault …they both lost money. That mattered little to Tom for he had a reserve, but to Ernst, this was a vital concern. In the end, as “Sir Thomas Beecham,” Tom became his country’s most hallowed musical force, while “Ernst Denhof” slipped into obscurity.

An immigrant from the Swiss-Austrian border area, Ernst came to live in Edinburgh in the early years of the last century. It is said that back home as a believer in music, he had organized a variety of events so, once he felt settled in his new post, he began harboring like thoughts. By 1910 he had a plan and how exciting it was! He had likely attended the historic presentation of Wagner’s Ring in English at Covent Garden in January 1908. Now he wanted to do the same in Edinburgh as the first offering outside of London, and if enough interest was shown, he would present it twice! It was a grandiose plan for certain, especially for a relative newcomer.

Most local newspapers thought he was daft! The TIMES took note on 8 March: “What makes a remarkable project still more remarkable is that it is due neither to the action of any organized body nor to the whim of a music-loving millionaire, but is entirely the outcome of the energy and enthusiasm of one man, Mr. Ernst Denhof, a local musician, whose first venture into the ordinarily thorny paths of operatic speculation this is. Unsupported by any guarantee, and unaided (or unhindered) by a committee, he has worked out all the details of the scheme himself…Briefly, the idea was to secure the services of all or most, of the singers who had taken part in the English Ring performances at Covent Garden, to engage the Scottish Orchestra and to entrust the musical direction to Mr. Michael Balling, who, on the recommendation of Dr. Richter, had conducted at the last Bayreuth Festival. Mr. Denhof, at the same time announced a number of provisional engagements, indicating the rates of subscriptions.”

Four days later, the Nation said much the same: “It looks, however, as if the impetus is to come not from London or Birmingham but from Edinburgh. We might have waited to doomsday before any of our ordinary operatic companies produced the `Ring of the Nibelung’ on a proper scale. It has been done during the past couple of weeks in Edinburgh, the motive force being Herr Ernst Denhof. He has, of course, had incredible difficulties to contend against. Some of them were inevitable; others might have been avoided if the venture had not aroused, as schemes of this kind always do, the jealousy of people who will do nothing themselves, but are always ready to throw cold water on the plans of more earnest and energetic men. Nor, if report speaks truly, has Herr Denhof had the support from the press of his own town any man engaged in so fine a work as this should have been able to count upon with confidence.”

To make his scheme more practical, Denhof managed to align himself with the Carl Rosa Company. Their people could be vassals in the Ring together with members of the Edinburgh Choral Union and choirs of both Messrs Kirkhope and Moonie. He could also present Carmen, Faust, Don Giovanni, Tannhäuser, Merry Wives of Windsor and Marriage of Figaro, interspersed amongst his Ring segments.

Denhof announced that veterans from the London Ring would form the heart of his cast, Amongst the notables: Agnes Nicholls would sing Brünnhilde and the mighty bass Robert Radford would sing Hunding and Fasolt. Through the good offices of the Berlin Opera, both members of the Maclennan family would appear: tenor Francis as Siegmund in Valkyrie and as Siegfried, and his wife, Florence Easton, would sing Freia, Sieglinde, the Woodbird in the first cycle and Gutrune. Edna Thornton was a rock solid Erda. Thomas Meux was Alberich, Sydney Russell, Mime and Frederick Austin sang Wotan and later The Wanderer. Michael Balling would conduct the orchestra of 82. Veteran E. C. Hedmondt would sing Loge and handle stage direction, and new scenery and costumes created in Germany would complete a mercurial package.

Both cycles emerged as artistic successes with the finances in the blue, slightly. Afterwards, in deep appreciation, Lord Dunedin, Lord Justice General for Scotland, on behalf of the subscribers, presented Michael Balling with a silver wreath and Mr. Denhof with a silver tray, saying, “Altogether, Mr. Denhof’s Ring fortnight in Edinburgh tempts one to dream pleasant dreams of the future of opera in this country.” The small surplus led Denhof to contemplate a tour of leading provincial cities in the coming autumn. It was a noble start!

Later that year, while Beecham remained in London wielding his baton, his Opera Comique Company rolled into Edinburgh for the week of 31 October, early in its seven month long tour to present a week of Tales of Hoffmann and Fledermaus performances. In The Evening News on 1 November, Beecham was acclaimed as “an active patron of British musical artists and composers. He is not a mercenary impresario, but a man who spends money on his opera schemes, by which the public benefits.” No doubt Ernst enjoyed Caroline Hatchard as Olympia in Tales of Hoffmann, recalling her work in his English Ring a few months earlier “as one of the charming Rhine Maidens,”

With Beecham’s forces soaking up most of the local entertainment budget, Denhof decided to shelve his plans and think of the spring of 1911. And indeed he was up and running with a three week tour that may have been of modest length, but certainly was immense in content. He set out to present a single cycle of the English Ring first in Leeds during the week of 28 March, in Manchester from 3 to 9 April and finally in Glasgow from 11 to 15 April. They were “firsts” in each case. The cast was a mixture of returnees and newcomers, the most notable absentee being the mellifluous Maclennan.

In Das Rhinegold, Frederic Austin was back as Wotan, as was Sydney Russell as Mime, Charles Knowles as Donner, Radford as Fasolt and Edna Thornton as Erda. Walter Hyde now became Loge, Charles Victor as Alberich in place of Meux. Toni Seiter sang Fricka replacing Marie Alexander. Fafner was Gaston Sargeant.

In The Valkyrie, Hyde now sang Siegmund, Radford powerful again as Hunding, Austin once more was Wotan, Florence Easton returned as Sieglinde, Toni Seiter continued as Fricka. Cecilie Gleeson-White sang Brünnhilde in Leeds but Agnes Nicholls assumed the role in the other cities.

Next John Coates appeared as Siegfried with Sydney Russell as Mime, Austin as The Wanderer, Charles Victor as Alberich, Gaston Sargeant as Fafner and Edna Thornton as Erda. As Brünnhilde, Mme. Gleeson-White sang in Leeds and Glasgow; Nicholls in Manchester.

Finally to complete The Ring, John Coates sang Siegfried in Twilight of the Gods, Florence Easton was Gutrune as before; Gleeson-White led off in Leeds as Brünnhilde but Nicholls sang in the other centres. Gunther sung in 1910 by Austin, was now interpreted by Charles Tilbury while Waltraute was repeated by Thornton. Hagen was Charles Knowles. They were a sturdy crew.

Denhof, now feeling his enterprise was maturing and beginning to turn the corner financially, he announced for 1912 his largest scheme to date. He would present The Mastersingers, The Flying Dutchman and Tristan und Isolde of Wagner, Gluck’s Orpheus, and as the pièce de resistance, Richard Strauss’s elaborate shocker, Elektra, first in Hull, then in Manchester, Liverpool, Leeds, Glasgow and Edinburgh.

On 26 February, the day he opened in Hull, the country was hit by a national coal strike. For the unlucky impresario, it was yet another blow, the cruelest so far.

A writer for The Daily Mail caught up to Denhof on opening night. “Generalissimo …You will verily deserve a jaunt in the Riviera after this struggle, I told this kindly, courteous impresario.”… “Ah! Yes, you do not know the rushes and strain of it! It is not over yet. I find Hull is willing, but tardy. Yes! Am I not right? They crowd the theatre after the first night or two – so? Eight hundred costumes or more have had to be procured for the Opera Festival in Hull this week. Ships are on the stage, tonight; a representation of Hell and Heaven another time; and bullocks, sheep, whippers, and snakes another!”

Setbacks be damned! He was committed. Vivid reports in Hull newspapers for the three Wagner operas and Elektra provide an inkling of what transpired.

In reviewing the Opening Night The Daily Mail wrote, “The massive masterpiece was given without `cuts’ of any kind, and with a triumphant wealth of detail not found outside Covent Garden on Gala nights…The dress circle was not quite half full, boxes were taken, the pit was moderately well filled, and the gallery showed no blank space whatsoever.” Frederic Austin was benign, sad and sympathy-compelling as Sachs… throughout the light bloom of Francis Maclennan’s characterization as Walther was a delight…Florence Easton a maidenly Eva, with fresh and ardent tone and dainty by-play… brilliant, flexible Maurice d’Oisly as David… but it was conductor Balling who was applauded for his magic.

Denhof had stinted not at all. A stickler for authenticity he brought to Hull diverse talents, such as designer and scenic artist, Herr Impekovem from Cologne, the chief authority in Germany for costumes and period, to paint the beautiful scenes in Denhof’s productions. To reinforce the chorus in Mastersingers in Leeds and Hull, Denhof hired members of the Leeds Choral Union, to achieve an “exceptionally powerful” result.

As The Flying Dutchman, Charles Knowles sang “the majestic but somber music with unmistakable power” while Maud Perceval Allen offered “all Senta’s music with a supreme sense of the dramatic. She never quailed from the cauldron of sound who arose bubbling and shrieking before her, at times. Her voice of power and tragic intensity dominated even Herr Balling’s forces.” Frederick Ranalow interpreted Daland’s affecting music.

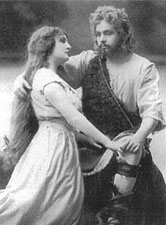

The next evening in Tristan and Isolda, “Madame Gleeson-White’s eminently intellectual qualities were noticeable, in her womanly Isolda…The duet, `Night of rapture rest upon us’ afforded Madame Gleeson-White and Mr. Maclennan a matchless opportunity. They made it seem the very delirium of love – an opium-dream, languorous and faint with sweetness.” Miss Toni Seiter, replacing Marie Brema, “was an expert and well-graced Brangana; though the carrying power of her voice was not on a par with its sweetness and neat production. The sinister Melot had a strong portraiture at the hands of Thomas Meux.”

On 28 February came the event for which everyone was thirsting, Strauss’s Elektra, sung for the first time in English. Munich-born Fritz Cortolezis, born in on the wings of Strauss’s recommendation, was at the podium. Florence Easton was ready in the title role. Marie Brema “was engaged also by wish of Strauss to sing Klytemnestra” but when her moment came, a severe cold kept her away. Doris Woodall sang.

“The Old Queen – not as given by Miss Doris Woodall – but as in the Germanized version, also is rather too clammy for our tastes – a revolting old sinner, with `sallow, bloated face.’ She is covered over and over with gems and `Talismans;’ her arms are full of armlets, her fingers bristle with rings. The lids of her eyes are larger than is natural, and it seems to cost her an unspeakable effort to keep from falling. ” There you have it – streaky and strong, the Teutonic foible for too heavy colouring. Miss Woodall did not wear the snakes, but (aided by the bells in the orchestra) rattled her metal charms instead. She forgot her `disease’ and was rather too active.

As this fury-haunted Queen, Miss Woodall was impressive in the required way, and reached a dramatic height when exclaiming through the window bars. `See how she defies me.’ Miss Woodall sang with just the right vitality of expression …and the similar outburst of anger and triumphant laughter were brilliantly treated.”

Florence Easton was virtually perfect in the name part. A born actress, no whit of baleful power was lost, though her voice was thin occasionally. Austin was “impressive” as Orestes, Edith Evans “a tender and likeable” Chrysothemnis and d’Oisly, “the wretched interloper Aegistheus, had little to do but that little is indelible in the memory.”

“Each time applause became more deafening. Five or ten minutes had to pass ere the onlookers awoke from the experience and filed out. We were glad to see the boxes occupied, the circle more than half full, the floor almost filled and the galleries quite so. No single person at the first production in English in Hull will ever erase the impression. We took a poll of the faces. And very few had an opinion expressed there! They were still in the throes of the excitement. They had come, some of them, to hear unspeakable things only audacious cacophonies, an epileptic fit in music, a fierce fancy by a Mad Mullah of Harmony with a touch of sadism in it! They left with the knowledge that for two hours it had been their privilege to listen to music complicated, indeed, and vehement sometimes beyond ordinary description, lurid, and passionate in colour. But it had also gorgeous suggestions, and some few lovely achievements in the lyric line!” After the final opera, Herr Denhof and his lieutenants were lauded for bringing “one of the most innovatory productions ever given in the Provinces.”

As the tour progressed, cast changes took place. In Manchester, Cecilie Gleeson-White stepped into the role of Elektra without any previous experience or stage rehearsal. Now recovered, “Madame Brema (as Brangana and Klytemnestra) shone again by reason of intense dramatic qualities; by sheer intellectual strength she dominated that wonderful first act of Tristan” Knowles added the role of Kurwenal while Julien Henry excelled as Beckmesser.

In some cases, initial curiosity failed to translate into packed houses later. In Manchester and Liverpool Elektra and Mastersingers drew quite well initially but less so when repeated. In Liverpool, Easton’s Elektra “was memorable in its histrionic as well as its vocal brilliance. Apart from the sensational features of this much-debated opera, its two performances failed to make a favourable impression.”

In Manchester The Musical Times reported on Orpheus, drawing attention to one of the country’s greatest international stars, a singer supreme at Covent Garden and at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. “Madame Kirkby Lunn’s lyrical powers were known to be very great, yet their true measure could not fully be realized until one had seen her in Gluck’s Orfeo.” There were visual delights too, “the solemnity of the scene by the tomb of Eurydice (Kate Anderson) surrounded by a grove of stately cypresses, the terror and mystery of Hades, and the bright, spring-like charm of Elysium, were most happily suggested.”

By the time they reached Leeds the impact of the miners strike was being felt, “With a restricted train service, and under the financial depression caused by so many businesses closing down, such an undertaking, which extends to some of the provincial towns, is bound to meet with less than it deserves. There were many vacant seats in the Leeds Theatre Royal last evening at the opening performance of The Mastersingers. Indeed the audience was by no means what it should have been even making allowances for the restricted area drawn upon.”

News from the financial area was not good. According to The Musical Times reporting on the Manchester segment in April 1912 said, “The high hopes formed of the future of opera during the recent `Denhof Operatic Festival’ conducted by (Michael) Balling and (Fritz) Cortolezis; the public support was much less than for The Ring dramas a year ago. Gloomy tidings reached us from Hull of a deficit of over 1000 pounds and the loss of the week’s run here cannot have been very much, if any, short of that figure…”

Now a lesser individual might have called it quits but not Herr Denhof. He was not discouraged and began to think of an even longer tour. Getting wind of these plans, Beecham decided to offer support by loaning a German conductor from his staff, Hans Schilling-Ziemssen, and conducting on occasion himself. Ernst, still flying high from his artistic achievements, was delighted by the offer and plunged ahead. After all, his robust Ring in Edinburgh for the first time in the provinces, Elektra the same in Hull, and Wagner and Strauss galore in Manchester, Leeds, Newcastle et al made for pretty heady stuff. With Beecham, he could expect to augment his laurels, or so he thought. He plunged ahead with planning and gladly assumed leadership of the tour during the autumn of 1913.

This was to be an auspicious event in every way. Twenty-seven principal singers supported by a chorus of a hundred, a ballet of twenty-four and an eighty-two piece orchestra, backed by ten management and staff. “To cover costs, Denhof had to rely on full houses everywhere,” which was certainly unrealistic and poor budget practice.

Playing to indifferent-sized audiences, they completed two weeks in Birmingham, trying vainly to achieve a debut mood. They moved on to Manchester and gave the first week of two, at which point Denhof realized he was in desperate straits. He was £4,000 in arrears! He decided to stop right there and move to disband the company. When he alerted Beecham, the latter’s reaction was predictable. Like the white knight on a charger or the US cavalry galloping to rescue beleaguered settlers, he raced to the scene. That very evening after the curtain descended on The Flying Dutchman, he addressed the troops, giving them every hope the enterprise would continue. A week would be needed to sort matters out; then they would re-open in Sheffield and continue till after a fortnight in Edinburgh. Beecham turned the reins over to his man of all miracles, Donald Baylis, and two accountants, and departed, leaving behind 240 much happier employees, and a disgruntled former colleague.

Before he left, Beecham launched a massive publicity campaign designed to goad the musical fraternity in Sheffield. Assaults in print upon the duty of the citizenry to art and the artist produced the desired effect. A full house and stony silence greeted Mr. Beecham when he arrived to conduct, and afterwards amidst oceans of applause, there arose cries of exultant derision, “Well, Tommy Beecham, are we musical?”

Feeling the gloom of personal failure, Ernst pondered what had gone wrong. Had he bitten off too much in his enthusiasm? With his earlier experience, why had he foundered in administration? He may well have asked himself why this situation had been allowed to happen at all.

Canny expert that he was now, Beecham would have detected the flaws in Denhof’s plan. After all, what kind of new show could expect to fill every seat every night, just to break even? Instead of throwing a hold on the proceedings to make changes, perhaps there was no time, he let it go ahead, thinking (and hoping) the veteran campaigner would pull it off. Ernst was left to sink or swim. When the tour foundered, Beecham was able to rise to the challenge and stage his remarkable revival, to his credit.

Even after he had gone, Ernst’s legacy was being appreciated in Leeds, “Productions were characterized by Mr. Denhof’s invariable thoroughness; his aim has always been not to consider how much he could dispense with, but how he could make his performances complete.” Alas, not necessarily a proven way to keep costs in line.

His great dreams dashed, Ernst returned to Edinburgh to spend the rest of his days as a teacher, his original occupation. In retrospect, one wonders if retaining his German name and using “Herr” instead of “Mr.” worked against him as in 1913 relations between Britain and Germany were deteriorating.

For the facts thanks to Dennis Foreman in Nottingham and Norman Staveley in Hull and to The Musical Times and other publications mentioned.

Published in For The Record, Autumn 2008