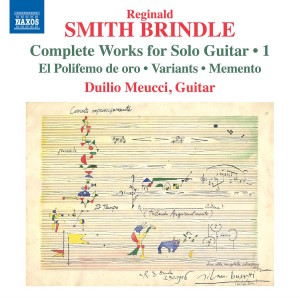

Reginald Smith Brindle (1917-2003)

Complete Works for Solo Guitar – Volume 1

Duilio Meucci (guitar)

rec. 2022, Newmarket, Canada

Naxos 8.574476 [69]

In his lifetime, Reginald Smith Brindle was not just a guitarist but a wide-ranging and quite successful British composer – his large-scale orchestral work Creation Epic was even performed at the 1964 BBC Proms. His first instrument was in fact the organ, and he seemed to have been a more capable organist than guitarist, but in the post-war years, like many others, he became keenly interested in the classical guitar and is nowadays chiefly remembered as a composer for that instrument; as he played it, he also wrote well for it and was lucky to have found himself in the right place at the right time: very early on, he somehow befriended a teenage prodigy from Battersea who was fast making a name for himself – none other than Julian Bream. For many years, Julian Bream’s 1967 recording of El Polifemo De Oro was most people’s introduction to Smith Brindle’s music, and although there have been other fine recordings of his guitar works and a few other chamber works in the decades since, there are still no commercial recordings of his organ and orchestral works, both of which were at least as significant a part of his oeuvre as his guitar works.

Smith Brindle wrote Nocturne for Bream in 1946, when Bream was only thirteen but by all accounts already a fine guitarist. It is a slow and expressive work with jazz-like harmonies, characteristic of Smith Brindle’s early works, which often sound as if they were composed by improvising on the fretboard. The resulting music is interesting but less substantial and well-designed than his later works. This also applies to the Etruscan Preludes (1949); nevertheless, both works are attractive and show a developing musical imagination. The five short Etruscan Preludes contain plenty of interesting harmonic ideas, in particular, and make a satisfying and varied set.

Smith Brindle went through three main musical stages: an early tonal period which includes the above two works, a middle serial period, and then, like many of his contemporaries, a third and final phase which was a synthesis between the two, and therefore a partial return to tonality. During the middle serial period, he stopped writing for guitar, mostly because he could interest neither publishers nor performers in his 1956 four-movement work El Polifemo De Oro, one of the earliest serial works. Bream did not record the work until a decade later, and in the meantime Smith Brindle had become disillusioned with the instrument.

It is a shame, as Polifemo is strikingly better than what came before; unlike his earlier pieces, it is the work of a composer first and guitarist second. A recognisable Brindle style is still there, but much more focused and intense. It remains one of his most visceral and colourful guitar works, with such melodic and rhythmic vitality – qualities which Duilio Meucci brings out with great skill, reminding us why this piece has endured in the repertoire. Meucci plays the 1981 revised version, which according to Smith Brindle’s autobiography was written, in the manner of some of Stravinsky’s revised works, so that he could avoid copyright issues and publish it with another publisher. In the opinion of the composer and others, the revised version is in some ways inferior to the original – perhaps in one of the future volumes Meucci will record the original version?

Most of the other works are not quite as extroverted as Polifemo. Being a guitarist, Smith Brindle understood the guitar’s potential when it comes to intimate and melancholy music. He also recognised that it thrives as a melodic instrument, and he had an ear for melodic lines that at times reminds me of his teacher, the great twentieth-century Italian composer Luigi Dallapiccola. Even Smith Brindle’s harmonies can be rather like melodies clustered vertically. Memento (1973) might be his best guitar work, and exemplifies these virtues. It is in two movements: one an agitated quasi-improvisation, the other slow and intense. The second movement has the feel of a tombeau, with its repeated motif of four semiquavers and its frequent use of descending harmonies.

Almost as good is Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night (1974) – again, Brindle does melancholy very well. Variants on Two Themes of J.S. Bach (1970) is the third stand-out work, and quite different from the others. Parts of it remind me of Benjamin Britten’s Nocturnal – it shares its darkness but not to the same extent its drama. Smith Brindle’s Variants uses a more formal style, perhaps, one that nods back to the Baroque, though the harmonies are never less than modern – and unlike Britten’s Nocturnal, we never hear the themes in their original form. None of these three works is often performed or recorded – in fact, this is the premiere recording of Variants. Meucci gives as convincing and interesting a performance as you could hope for, superior to the few other available recordings – it’s worth getting the album just for these three works.

I’m less sure about what one might call the ‘percussion pieces’ – Three Inventions (1977) and Four Poems of García Lorca (1975) – which I admit I enjoy more as a player than a listener. Three Inventions are essentially concert studies from his three-volume set of guitar music titled Guitarcosmos (inspired by Bartok’s Mikrokosmos). The first invention is aleatory music, the second solely explores percussive effects on the guitar, and the third, which is by far the most beautiful of the three (and the only one without percussive effects), is a very spare homage to John Cage. This is the first time Three Inventions has been professionally recorded. Four Poems is full of rasgueado, drum rolls, tambora, and other ways of striking the instrument. In between, we get alluringly spare musical lines. This all makes for a wide musical landscape, but to my ears it seems, after the second or third listen, a rather empty one. I prefer Smith Brindle when he is more purely musical.

Duilio Meucci’s playing is excellent throughout, and the album has the clear, resonant recorded sound that one expects from Naxos. I look forward to the second volume, which will presumably include the five sonatas Smith Brindle wrote. Maybe we can also hope that the album will help encourage other instrumentalists to take up Smith Brindle’s music, especially as now seems to be the moment for new recordings championing the cause of neglected twentieth-century British composers, from William Baines to Elisabeth Lutyens.

Steven Watson

Previous review: Rob Barnett (June 2023)

Help us financially by purchasing from