Sir William Walton (1902-1983)

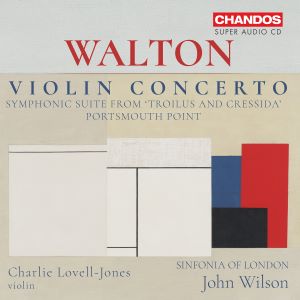

Violin Concerto (1936-1930, revised 1943)

Symphonic Suite from Troilus and Cressida (arr. Christopher Palmer, 1987)

Portsmouth Point (1924-1925)

Charlie Lovell-Jones (violin)

Sinfonia of London/John Wilson

rec. 2024, Church of St. Augustine, Kilburn, London

Chandos CHSA5360 SACD [64]

I am not too fond of William Walton’s Violin Concerto. Conscious of that, I decided to listen several times in an attempt to appreciate the work more. I knew from an initial dip that the sound on this new recording was exceptionally good.

The work has no slow movement as such but in several places the first movement makes the most of its principal melodic idea. I find it the most attractive: the other two movements contain, in my view, too much virtuosic jumping around with the violin plucking, scrubbing and scraping. Interestingly, the creation of the ferocious tarantella in the second movement was spurred by Walton being bitten by a tarantula.

I mentioned that I was determined to indulge in repeated listening. After the umpteenth playing of the first movement, as the music progressed, I found myself humming George Gershwin’s Summertime. In fact, the principal melody bears a distorted resemblance to the song’s tune. I say ‘distorted’ because Walton diverges significantly in the first bar or two. Yet the resemblance is there, and now I cannot erase it from my mind. Walton was undoubtedly influenced by jazz and American music, so maybe the observation is not so outlandish as it might seem.

I think it is unusual for a recording of a major-repertoire violin concerto to have the leader of the orchestra as soloist. I had been unfamiliar with Charlie Lovell-Jones, but was not surprised to read about his accomplishments, which include outstanding academic achievements in musicology. That, and the quality of the Wilson/Sinfonia Chandos productions, mean that unsurprisingly they surmount with apparent effortlessness the challenges of this Concerto. The balance between soloist and orchestra is spot on. The violin get just the right amount of emphasis in the mix, and the orchestra retain full impact.

For my taste, the principal attraction here is the Symphonic Suite from Troilus and Cressida, which Lady Walton commissioned from Christopher Palmer. The opera was not too successful due to fairly common preferences amongst trendy critics for progressive or avant-garde music. Things were not helped by initial performance problems due to the conductor’s lack of preparation. At least one critic, the hostile Peter Heyworth, described its essentially romantic idiom as ‘deeply embedded in the stagnant waters of the past’. The opera did get performances in San Francisco, New York and Milan. Walton later adapted it to enable Dame Janet Baker to sing Cressida’s part.

The four-movement suite follows the main events of the opera. It begins with The Trojans (Prelude and Seascape). Dark and gloomy at first, with low drumbeats and bassoons, it denotes the Trojans’ feeling of being cursed, and their prayer for aid to Pallas Athena. The grim mood lifts to a seascape of glittering waves. Troilus pleads with Aphrodite to bless him with the love of a mortal. Cressida appears, represented by oboe and strings. The end of Act 1 features amorous music for the pair. Palmer introduces it as the movement ends. The various sections of the orchestra get their chance to shine, helped by the superb recording.

The second movement, a Scherzo associated with Pandarus, is playful, skittish and good-tempered, with skirls, arabesques and roulades on the winds. Then a storm threatens and Pandarus accommodates Cressida and Troilus overnight. This forms the trio of the scherzo, corresponding to Cressida’s aria At the haunted end of the day. The movement ends with a reintroduction of the opening jaunty music associated with Pandarus.

Palmer intended the third movement, The Lovers, to bear the emotional burden of the suite. It builds to intensely rising tides of climax. Walton rather laconically described it as pornographic. This is not a smooth, strings-dominated climax as in the slow movement of Rachmaninov’s Second Symphony. In fact, it seems to me that the entire orchestra engages in a series of interlinked crescendos, with percussion to the fore. The superb recording makes the percussion very effective. There follows post-coital tenderness, described by a quietly lovely extended section, at the end of which the lovers depart.

In the final movement, the soulful voice of the cor anglais carries Cressida’s lament for her absent lover. Diomede arrives to the triumphant sound of trumpet fanfares, determined to claim Cressida for himself. This brief passage echoes the grandeur of Walton’s Coronation and Imperial pieces. Troilus, desperate to rescue Cressida, meets a tragic fate at the hands of her father. The cor anglais and strings weave the sorrowful strains of her plea. She longs for Troilus to look back at her from his eternal sleep. In despair, she takes her own life with his sword.

I thoroughly enjoyed Palmer’s arrangement of Walton’s late-Romantic music, which stands in stark contrast to the far more commercially successful productions of Benjamin Britten’s works. It appears that Britten and Peter Pears were somewhat dismissive of Troilus and Cressida, even if Pears took the role of Pandarus in the initial productions. By that time, however, the relationship between the two composers had already deteriorated.

The remaining work on this superbly engineered recording is the brief overture Portsmouth Point, which I find unmemorable and noisy. Yet it is obviously complex rhythmically, and shows off the orchestra’s virtuosity and Chandos’s spectacular sound.

The booklet presents the genesis of all the works and the usual biographical details.

Jim Westhead

Previous reviews: Philip Harrison (April 2025) ~ Nick Barnard (May 2025)

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free