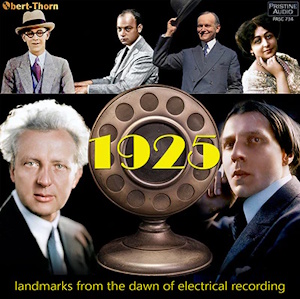

1925: Landmarks from the Dawn of Electrical Recording

rec. 1920-1925

Pristine Audio PASC734 [2 CDs: 140]

This pair of CDs celebrates the 100th anniversary of the single most revolutionary technical change in the history of recorded sound. There have, of course, been many other advances since then – the LP, stereo, the CD – but though this last, with its move to digital recording, could make a claim to be as revolutionary in purely technical terms, none of them made an equivalent leap in basic, observable sound quality. These CDs trace the adoption of the new technology from its first surviving, experimental example to a number of recordings made in the first few months after its adoption by the two most important recording companies of the time. A fair amount of the content is not what one would immediately expect from a Pristine product, but it is hardly a surprise that popular music and historic events should of necessity be included if the survey were to be remotely comprehensive. In this review, I will concentrate on the classical pieces, but also consider some of the others.

The first and last items are examples of the historic events which electrical recording allowed to be captured in ways impossible by the acoustic method. The ceremony of the reburying of the Unknown Soldier in his tomb in Westminster Abbey on 11 November 1920 is widely accepted as the first electrical recording to be issued. Such an event could not have been recorded acoustically in any satisfactory sort of way, but it must also be admitted that the sound quality does not really sound anything like an electrical recording. Both high and low frequencies are as absent as they would have been on an acoustic recording, but the record is nevertheless a moving echo of the event. The next track, which moves us forward three years, does convey something tangibly better than anything recorded acoustically. I have never heard of any attempt even being made to record a large organ acoustically, but in 1923 Jesse Crawford’s performance on the organ of the Chicago Theater is remarkably realistic. Electrical recording’s experimental, hit and miss nature at this stage is demonstrated by the next track of a small dance band with singer, recorded a month later by the same engineer, but being distinctly poorer in sound quality.

The first track of any real musical interest follows a year after the previous track. This is of the Ukrainian pianist Mischa Levitzki in Chopin’s Waltz in E minor, Op. posth. recorded for Victor. After the organ, the piano was the single instrument most difficult to record convincingly by the old process. Levitzky’s recording is a marked improvement on anything before, and though the tone is still rather clangy, both bass and treble have a realism hitherto unknown. It must be said, though, that Victor were not at their best with the piano. Their piano recordings actually seemed to get worse in the late 30s and early 40s, being dreadfully thin and metallic, sounding like no piano known to man. Contemporary European recordings by almost any company were markedly more realistic. This performance is a distinctly serious, almost manic, affair with little of the insouciant grace to be found in Cortot or the cool sophistication of Lipatti. The fortissimo passages are almost banged, and the final bars verge on hysteria. I found this unusually psychological approach an interesting and convincing alternative.

Six months later, the earliest vocal recordings by an important classical artist were being made. The increase in fidelity is very slight for the individual human voice, so there is no revelation here, especially with a singer like de Luca, who was a great artist but whose voice was comparatively slight. The “Stornello” by Cimaro is rather undistinguished little song, but is charmingly sung, though the loosening of de Luca’s vibrato is to be heard even at this date (he continued singing for almost another quarter century).

After a couple more popular items, there is double-sided “miniature concert” by a number of Victor’s standard American artists. This is essentially a sample record, with eight different artists/groups giving excerpts from popular repertoire, linked by a narrator. I found the piano contributions by Frank Banta, and the remarkable saxophone virtuosity of Rudy Wiedoeft the most enjoyable (and thanks to the narrator I now know how to pronounce his name: Weedoft). The narrator’s “We’ll see you on the other side” at the end of the first part had a spiritualist connotation which tickled me greatly.

The next classical artist is the contralto Margarete Matzenauer. We are given two of the earliest-recorded classical vocal sides issued by Victor. Matzenauer was born in Timișoara in what was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (it is now in Romania) in 1881. She made her Met debut in 1911, singing for nineteen seasons with them, and remained in the US until she died in 1963. She has never been a singer who has made much of an impression on me, being another of those rather staid contraltos like Louise Kirkby-Lunn and Louise Homer whose records make everything they sing sound as though it’s from Elijah. This works quite well in “Ah! mon fils” (Meyerbeer’s Prophète), and Fidès’ sadness is well conveyed, though the top B flat is rather a scream and the vibrato somewhat loose. In the lively Mexican song “Pregúntales á las estrellas”, however, she is well out of her comfort zone, lacking any verbal colouring or Latin rhythmic snap. Why on earth did she record a song so unsuited to her vocal personality?

On the day after Matzenauer, one of the great pianists of the 20th century visited the Victor studios for his first electrical session. The two sides by Alfred Cortot transferred here are exquisite. I particularly liked his own transcription of Schubert’s “Litanei”, where the melody is given a wonderful depth of sonority in its first iteration, then with much more overt passion an octave higher on its second. The Second Impromptu is also full of character, contrast and interest, and the piano tone is remarkably good. Two days after Cortot, one of Victor’s house conductors, Josef Pasternack, recorded Bizet’s Petite Suite, two movements of which are transferred here. This recording is also remarkably good (it apparently remained in the catalogue until the 1950s) and both movements have a splendid verve, momentum and crispness of attack. Pasternack was clearly more than a mere stick-waver.

The second CD contains more extensive pieces, though begins with a short pot-boiler in the form of the Prelude to Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana (omitting Turiddu’s Siciliana). This is interesting for at least two reasons: first, that it must be the first electrical recording of the orchestra of the New York Metropolitan, and secondly that it is a Brunswick recording using their short-lived “light ray” system. The orchestra’s playing, under Gennaro Papi, is flexible and convincing, if nothing remarkable. The “light ray” recording system was something of a disaster, producing recordings that were strident and congested, and it is no surprise that it was ditched in 1927. This must have been particularly annoying for the German Grammophon company, which had also adopted it. They had made a considerable number of recordings with important artists (including complete works conducted by Richard Strauss), and ended up having to re-record many of them in 1928/9. The present one, which is an undemanding piece in recording terms, comes over rather well – which does make me wonder how much help Mark Obert-Thorn’s transfer has given it.

The next track transfers one of the most famous recordings of this early period, Saint-Saëns’ Danse macabre, the first electrical recording by Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra. This was the demonstration record for displaying what the new system could do, and still sounds remarkably good. The violinist, Thaddeus Rich, who was leader of the orchestra from 1906 to 1926, plays the solo part splendidly, and the performance is as full of character as one would expect from this combination of performers.

By far the most extensive piece on these CDs comes next in the form of the first electrical recording of a complete symphony, Tchaikovsky’s 4th. I was particularly interested to hear this as it is conducted by Sir Landon Ronald, a man now almost completely forgotten, but who was an important musical presence in the UK at this period. I have him on many records conducting (or playing) the accompaniments, but not a single purely orchestral work. This performance is really quite good, though at no point does it approach Mengelberg’s recording of three years later. Unsurprisingly, the recording sessions were clearly still made on the old recording rooms designed for acoustic recording, as the acoustic is absolutely dead. The opening brass fanfares don’t really have the dramatic flair or sense that something momentous is about to happen which they ideally need. At about 3.00 to 6.15 into the first movement the excitement increases, but at times the music just plods. There is little of the rhetorical flourish that the horn call at 7.00 needs. The more obviously dramatic parts are quite well done, but at other times the performance is dogged rather than exciting. As Mark Obert-Thorn mentions in his note, they were still using a tuba to boost the string bass line (something essential on an acoustic recording), and this is both very obvious and very irritating in the sections at 4.40 to 6.00 and 12.00 to 13.15 minutes in the first movement, where it plods along in the most lugubrious manner. I can’t actually hear any double bass sound at all here. The second movement is a little flat-footed, though Ronald uses quite a lot of rubato, but there is a nice momentum to the middle section. There is a great deal of string portamento – only a few years later it would have been much less. 1925 was pretty well the last year before the leaner, modern orchestral style really began to take hold; sadly, by 1935 portamento had almost entirely disappeared from orchestral string playing. The style of the new BBCSO (founded 1930) and LPO (founded 1932) are very different from the RAHO (which was disbanded in 1928) – a real musical changing of the guard. The third movement is the most satisfactory. Though the pizzicato ensemble does not match any good modern orchestra, the Royal Albert Hall Orchestra is lively and characterful, and the woodwind (especially the piccolo) in the middle section are very fine. The final movement is also quite exciting, and the recording is astonishingly good for a hundred years old.

The final tracks will undoubtedly be of more interest to American listeners than British as they consist of twenty-two minutes of the inauguration of Calvin Coolidge as president. The quality of the recording is exceptionally good, with almost every word clear and comprehensible. Although I doubt that even American buyers will listen to it more than a couple of times, Coolidge makes some noteworthy points – “the physical configuration of the earth has separated us from all of the old world, but the common brotherhood of man, the highest law of our being, has united us by inseparable bonds with all humanity.” Later on he says, “Our private citizens have advanced large sums of money to assist in the necessary financing and relief of the old world. We have not failed, nor shall we fail, to respond whenever necessary to mitigate human suffering and assist in the rehabilitation of distressed nations.”

This is an interesting and largely enjoyable set giving an excellent panorama of the first few years of electrical recording. The transfers are first rate and the presentation is much more comprehensive than is usual with Pristine.

Paul Steinson

Previous review: Jonathan Woolf (February 2025)

Availability: Pristine ClassicalContents

CD1

1. MONK Abide with me (2:50)

2. DYKES Recessional (3:34)

Choir, Congregation and Band of H. M. Grenadier Guards

Recorded 11 November 1920 in Westminster Abbey, London ∙ Matrices: unknown ∙ First issued on unnumbered Columbia “Memorial Record”

3. JONES & KAHN The one I love belongs to somebody else (3:17)

Jesse Crawford, organ

Recorded c. December, 1923 in the Chicago Theater, Chicago ∙ Matrix: 447 ∙ First issued on Autograph (no catalog number)

4. BERLIN All alone (2:52)

Dell Lampe Orchestra from the Trianon Ballroom/Al Dodson, vocal chorus

Recorded c. November, 1924, Chicago ∙ Matrix: 658 ∙ First issued on Autograph 604

5. CHOPIN Waltz No. 14 in E minor, Op. Posth. (2:51)

Mischa Levitzki, piano

Recorded 19 November 1924, New York ∙ Matrix: 6466-1 ∙ Columbia (unpublished on 78 rpm)

6. CIMARA Stornello (Son come i chicchi) (3:03)

Giuseppe De Luca, baritone/Orchestra conducted by Rosario Bourdon

Recorded 17 February 1925, Camden, New Jersey ∙ Matrix: WER-3719 ∙ Victor (unpublished on 78 rpm)

7. SMYTHE & GILLHAM You may be lonesome (2:55)

8. STANLEY, HARRIS & DARCEY I had someone else before I had you* (3:17)

Art Gillham, piano and vocal

Recorded 25 February 1925 in New York ∙ Matrices: 140125-7 & *140394-2 ∙ First issued on Columbia 328-D

9. THE EIGHT POPULAR VICTOR ARTISTS A miniature concert (9:29)

Opening Chorus; “Strut Miss Lizzie” – Frank Banta, piano; “Love’s old sweet song” – Sterling Trio; “Friend Cohen” – Monroe Silver, speaker; “When you and I were young, Maggie” – Henry Burr, tenor; “Casey Jones” – Billy Murray, tenor and Chorus; “Sweet Genevieve” – Albert Campbell, tenor and Henry Burr, tenor; “Saxophobia” – Rudy Wiedoeft, saxophone; “Gypsy Love Song” – Frank Croxton, bass; “Carry me back to old Virginny” – Peerless Quartet; “Massa’s in de cold, cold ground” – Chorus

Recorded 26 February 1925 in Camden, New Jersey ∙ Matrices: CVE 31874-3 and 31875-4 ∙ First issued on Victor 35753

10. GILPIN Joan of Arkansas – Medley (3:15)

Mask and Wig Glee Chorus; Orchestra conducted by Nathaniel Shilkret

Recorded 16 March 1925 in Camden, New Jersey ∙ Matrix: BVE 32160-2 ∙ First issued on Victor 19626

11. GILPIN Joan of Arkansas – Buenos Aires (3:37)

Arthur Hall, tenor; Bernard Baker, cornet solo; International Novelty Orchestra conducted by Nathaniel Shilkret

Recorded 20 March 1925 in Camden, New Jersey ∙ Matrix: BVE 32170-2 ∙ First issued on Victor 19626

12. MEYERBEER Le prophète – Ah, mon fils! (4:36)

13. MEXICAN FOLK SONG Pregúntales á las estrellas* (3:23)

Margarete Matzenauer, contralto; Orchestra conducted by Rosario Bourdon

Recorded 18 March 1925 in Camden, New Jersey ∙ Matrices: CVE 31632-3 and *BVE 31629-4 ∙ First issued on Victor 6531 and *1080

14. SCHUBERT (arr. Cortot) Litany (3:29)

15. CHOPIN Impromptu No. 2 in F sharp major, Op. 36* (4:41)

Alfred Cortot, piano

Recorded 21 March 1925 in Camden, New Jersey ∙ Matrices: CE 22512-11 and *31689-5 ∙ First issued on Victor 6502

BIZET Petite suite (from Jeux d’enfants)

16. 1st Mvt.: Marche (2:09)

17. 3rd Mvt.: Impromptu (1:03)

Victor Concert Orchestra conducted by Josef Pasternack

Recorded 23 March 1925 in Camden, New Jersey ∙ Matrix: BE 32179-3 ∙ First issued on Victor 19730

18. METCALFE (arr. Andrews) John Peel (2:53)

19. WADE Adeste fideles* (2:43)

Associated Glee Clubs of America

Recorded 31 March 1925 in the Metropolitan Opera House, New York ∙ Matrices: W98163-1 and *W98166-1 ∙ First issued on Columbia 50013-D

CD 2

1. MASCAGNI Cavalleria rusticana – Prelude (4:45)

Metropolitan Opera Orchestra conducted by Gennaro Papi

Recorded 8 April 1925 in Room No. 3, 799 Seventh Avenue, New York ∙ Matrix: XE 15472 or 15473 ∙ First issued on Brunswick 50067

2. SAINT-SAËNS Danse macabre, Op. 40 (7:19)

Thaddeus Rich, solo violin

The Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Leopold Stokowski

Recorded 29 April 1925 in Camden, New Jersey ∙ Matrices: CVE 27929-2 & 27930-2 ∙ First issued on Victor 6505

TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No. 4 in F minor, Op. 36

3. 1st Mvt.: Andante sostenuto (17:38)

4. 2nd Mvt.: Andantino in modo di canzona (7:51)

5. 3rd Mvt.: Scherzo: Pizzicato ostinato (5:22)

6. 4th Mvt.: Allegro con fuoco (8:45)

Royal Albert Hall Orchestra conducted by Sir Landon Ronald

Recorded 20, 21 & 27 July 1925 in Hayes, Middlesex ∙ Matrices: Cc 6374-2, 6375-3, 6376-3, 6377-2, 6378-2, 6379-2, 6381-1, 6410-1, 6380-5 & 6382-2 ∙ First issued on HMV 1037/41

Inauguration of Calvin Coolidge as President of the United States

7. Oath of Office (given by Chief Justice William Howard Taft) (0:57)

8. “My Countrymen . . .” (2:04)

9. “It will be well not to be too much disturbed . . .” (3:28)

10. “Our private citizens have advanced large sums of money . . .” (3:33)

11. “There is no salvation in a narrow and bigoted partisanship” (3:25)

12. “. . . they ought not to be burdened . . .” (3:34)

13. “Under a despotism the law may be imposed . . .” (3:24)

14. “. . . built on blood and force” (0:51)

15. Ruffles and Flourishes/Hail to the Chief (U.S. Marine Band) (1:11)

Calvin Coolidge, speaker

Recorded 4 March 1925 in Washington, D.C. ∙ Matrices: 51175/81 ∙ Columbia (unpublished on 78 rpm)