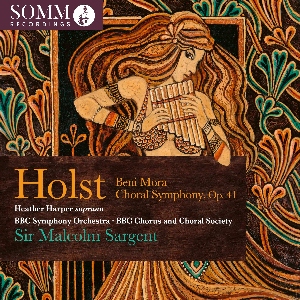

Gustav Holst (1874-1934)

Beni Mora Op. 29 No. 1 (1909-10)

Choral Symphony Op.41 (1923-24)

Heather Harper (soprano)

BBC Chorus and Choral Society

BBC Symphony Orchestra/Sir Malcolm Sargent

rec. August 1956, Kingsway Hall London (Beni Mora), 22 January 1964, Royal Festival Hall London (live broadcast)

Texts included

SOMM Recordings Ariadne 5040 [66]

In 2024 SOMM earned the gratitude of Holst devotees by issuing a fine two-disc tribute to Gustav Holst in his 150th anniversary year (review). The set allowed us to hear five conductors at work, one of whom was Sir Malcolm Sargent, who led a live 1945 performance, given in New York, of The Perfect Fool ballet. Now, they’ve followed that up with a pair of performances both of which are under the direction of Sir Malcolm. The present set has already been reviewed by my colleague Nick Barnard, who pointed out that both of these performances have appeared on CD before. However, I’ve not heard either recording before so I came fresh to them.

Beni Mora was recorded under studio conditions for HMV. In his valuable booklet essay, Simon Heffer points out, not in a critical fashion, that Sargent’s performance is on the swift side as compared with other recordings. It seemed to me that the performance was never unduly hasty. Sargent ensures that the First Dance has good life and plenty of colour. The Second Dance may seem on the brisk side but, after all, the tempo marking is Allegretto; I feel that Sargent’s tempo works very well. I admire the textural clarity of the performance. In the concluding ‘In the Street of the Ouled Nails’ I think the pace is well-judged. The piece revolves around an insidious little phrase that Holst heard in a street in Algiers, which is repeated, Simon Heffer tells us, 163 times. Effectively, the tune functions as a quasi-ostinato and such is the variety of Holst’s invention that the device never becomes wearisome. I thought this performance was exciting.

The Choral Symphony is an unusual work and though there have been, I think, three studio recordings of it, the symphony is rarely encountered in the concert hall. I think I understand why this should be. The symphony seems rather diffuse to me and I’m not sure that its cause is helped by the imagery, replete with Classical and literary allusions, of the poetry by John Keats which Holst selected. The work certainly has its moments but it seems to me to lack the blazing originality, focus and compression of The Hymn of Jesus (1917-19).

I first got to know the Choral Symphony through Sir Adrian Boult’s 1974 EMI performance, which was the work’s first recording. During my listening for this review, I deliberately refrained from making any comparisons, save for one; my reasoning was that Boult had the advantage of working under studio conditions whereas Sargent’s is a one-off, live performance with no chance of any patching; consequently, one would not be comparing apples with apples. I did, however, make one exception, as I said. The Symphony opens with a short Prelude, ‘Invocation to Pan’. For most of this the choir quietly sings the text in a unison monotone against a hushed orchestral accompaniment. That sounds as if it should be easy for the choir but, actually it’s quite hard to maintain pitch and ensemble and Sargent’s choir doesn’t quite pass the test, whereas Boult’s choir does; they are much more incisive. The reason I mention this is because I don’t think that Sargent helps his singers by adopting a fairly measured pace. Boult is more animated – he takes 2:55 for this section against Sargent’s 4:43 – and Boult’s speed works much better; I don’t believe he sacrifices any mystery by taking the music more swiftly than Sargent does. Thereafter, though, it seems to me that Sargent judges things pretty well.

After the Prelude there are four movements. The first opens with an orchestral passage dominated by a modal violin solo. As in the Prelude, Holst conveys a sense of mystery; Sargent and his orchestra fulfil this intention – the violinist plays beautifully. Sargent has the great asset of the young Heather Harper as his soprano soloist (she would have been 33 at the time of this concert). She sings the opening solo in an excellent fashion and, indeed, she’s on fine form throughout, singing with admirably clear tone and diction. After her solo comes an extended passage of lively music as the choir sings in praise of Bacchus; hereabouts, I think Sargent’s chorus is on much better form than was the case in the Prelude, investing the music with life. Sargent himself imparts energy into the music-making. In the slow movement, ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’, Holst’s music is very beautiful and has a lot of poetry in it. This performance is focused and, once again, Sargent is able to convey the mysterious nature of Holst’s music. In this movement Holst resists the temptation to involve the soprano soloist until she is called upon to deliver the closing phrase: ‘that is all / Ye know on earth and all ye need to know’. It’s perhaps surprising that in this movement Holst chose to give so few of Keats’s lines to his soprano but that makes her delayed entry all the more effective.

Two poems are set in the Scherzo – SOMM helpfully place each one on a separate track. This movement is sung entirely by the chorus. Sargent’s singers do well. They have an awful lot of text to sing and even though the movement is quite short – less than six minutes in duration – there’s little respite for them. The energy of their performance can’t be doubted. I wonder to what extent Holst was motivated to write this symphony by the example of his great friend Vaughan Williams’ A Sea Symphony. The two works are very different but the thought came to my mind because the finales of both symphonies are the longest and contain some of the most interesting, if discursive music in the respective works. Heather Harper’s unaccompanied solo at the start of this movement is ideally poised. Indeed, her contribution to the finale is highly impressive throughout; her singing of the delicately set stanza that begins ‘Next thy Tasso’s ardent numbers…’ is outstanding in its expressiveness. The chorus also rises to the challenges that Holst sets them. The movement plays for 18:55 and I think the greatest compliment I can pay to Sargent and his musicians is to say that it did not seem to last that long.

All in all, I think this is a very good account of the Choral Symphony. I have to be honest and say that the performance hasn’t quite assuaged my doubts about the piece itself. Earlier, I referenced Vaughan Willams’ A Sea Symphony. Comparing the two works, I feel that VW’s is the more successful, though I readily acknowledge that this may be because I know VW’s score infinitely better. I think, though, that there are other issues. For one thing, despite its rather vaunted imagery, the poetry by Walt Whitman which VW chose to set exerts a rather more direct appeal to the listener. Crucially, I think that the melodic material in A Sea Symphony is stronger and more memorable than is the case in Holst’s work. I think that choirs will find VW’s music more rewarding to sing and, if only for that reason, I think it’s unlikely that Holst’s Choral Symphony will be programmed in preference to his great friend’s choral symphony. It’s all the more important, therefore, that we have recordings of Holst’s piece available to us. A modern studio recording is always going to be a purchaser’s first choice, not least because those recordings can reveal more detail, especially in the orchestra, than a sixty-year-old radio recording can hope to do. However, Sargent offers a considerable performance, caught on the wing, and his version is an important contribution to the work’s discography.

Lani Spahr has done his usual fine job of audio restoration on these analogue recordings. The Beni Mora recording was made in stereo under commercial studio conditions; the sound has come up very well indeed. I don’t know what the source material was for the Choral Symphony recording, which is in mono. Inevitably, the sound is neither as clear nor as bright as is the case on the Beni Mora recording; that’s only to be expected. The voice of Heather Harper is relayed with great clarity. The choir can also be clearly heard but the bass end of the orchestra is somewhat indistinct in quiet passages. That said, Sargent’s interpretation is not compromised; one gets a very good appreciation of the performance. Simon Haffer’s booklet essay is informative and perceptive.

This is a very valuable archive issue, which is self-recommending to Holst enthusiasts.

John Quinn

Previous review: Nick Barnard (April 2025)

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free