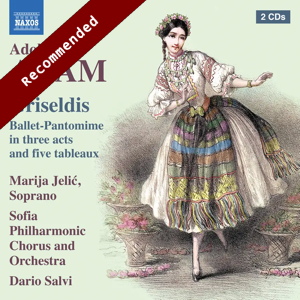

Adolphe Adam (1803-1856)

Griseldis, ou Les cinq sens (1848), Ballet-pantomime in three Acts and five Tableaux

Marija Jelić (soprano), Vesela Tritchkova (harp), Stefan Stefanov Vrachev (harmonium)

Sofia Philharmonic Chorus

Sofia Philharmonic Orchestra/Dario Salvi

rec. 2024, Bulgaria Hall, Sofia Philharmonic, Bulgaria

First recording

Naxos 8.574621-22 [2 CDs: 95]

You may have noticed that the two companies based at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, have recently adopted the new portmanteau title of The Royal Ballet and Opera. Its website quite correctly describes the renamed organisation as “bringing together two world-class performing companies”, even if it simultaneously overeggs the pudding by designating the whole thing as “a cultural powerhouse”. However, while opera and ballet companies are often linked for administrative purposes and even share theatres, we still, I think, tend to regard them as inhabiting separate silos. Many patrons still consider themselves as either ballet fans or opera fans. Who, after all, thinks of himself or herself as a cultural powerhouse fan?

No opera enthusiast, I suspect, goes to a performance of, let’s say, Andrea Chenier expecting that, as she awaits the tumbril that will take her to the guillotine, the much put-upon Maddalena di Coigny will throw herself energetically into a sequence of 32 fouettés en tournant, or that she and her beloved Andrea will suddenly launch into a romantic pas de deux. Similarly, a rapt audience watching Swan lake would no doubt be completely flabbergasted to see the prima ballerina stop dancing, advance to the front of the stage and burst into lyrical song. And yet, at the first performance of Adolphe Adam’s ballet Griseldis in February 1848, that, to the utter discombobulation of the Paris Opera patrons, was exactly what the celebrated dancer Carlotta Grisi did.

As it so happens, Madame Grisi was actually an accomplished singer who had occasionally been offered professional operatic roles, so we can probably assume that she made at least a reasonable job of it. That, however, is not the point, for, even if ballet and opera companies have long shared resources and theatres, the general assumption has been that ballet showcases dancing and that opera is for singing. Many balletomanes prefer that distinction to remain absolute and I am sure I cannot be the only member of the audience who finds it at the very least disconcerting whenever dancers sing, cry out or otherwise vocalise – as they so annoyingly do, for instance, in Carlos Acosta’s Royal Ballet and Birmingham Royal Ballet productions of Don Quixote.

If its leading dancer’s unexpected foray into song were its only claim to historical distinction, Adam’s Griseldis might now been recalled only as the answer to a likely question in a pub quiz. In fact, however, there is rather more to it than that.

Adam once remarked how composing ballet scores came to him much more easily than writing operas. It was not so much work, he claimed, as it was having fun (“On ne travaille plus, on s’amuse”). As several contemporary reviews were quick to point out, that sense of joie de vivre certainly permeates Griseldis, the 11th of the composer’s 14 ballets. “What lovely tunes! What zest! What coquetry! What vivacity!”, wrote one critic, “M. Adam is a magical musician; he too has the sixth sense, which is that of poetry. There is in Griseldis a provision of waltzes, polkas, and motifs to drive all the maestri of the genre to despair, and the whole so skilfully arranged, so perfectly appropriate to the situation, that one can say of the music of Griseldis, that it is a veritable score, and the worthy counterpart of Giselle. Honour therefore to Mr. Adolphe Adam! Half the success is his!”. Meanwhile, another reviewerresponded with equal enthusiasm, observing that “This composer, already known as a master of the genre, has truly outdone himself. There are in his score a host of waltzes, mazurkas, polkas, and quadrille motifs that all Europe will soon dance to.”[Quotations taken from Robert Ignatius Letellier and Nicholas Lester Fuller Adolphe Adam, master of the Romantic ballet, 1830-1856 [Newcastle upon Tyne, 2023], p. 609.]

In spite of the universal praise accorded to its music, Griseldis never became, however, a permanent part of ballet repertoire. Its plot isn’t necessarily the problem for it is no more inconsequential than that of virtually any other mid-19th century ballet. The central male character, Elfrid, heir to the throne of Bohemia, is an enervated and listless young man, somewhat reminiscent of his later counterpart depicted in Tchaikovsky’s Swan lake. In the course of a lengthy journey to Moldova, where he is to enter into an arranged marriage with the princess Griseldis, the prince repeatedly chances upon and dreams of a mysterious, unknown girl. Over the course of a series of romantic encounters she reawakens, in turn, Elfrid’s atrophied senses of sight, hearing, touch, smell and taste and, finally, insight. The revitalised prince arrives in Moldova determined to reject his fiancée Griseldis and to search instead for the strange girl he had met en route. In a predictably happy ending, he discovers that it was Griseldis herself who had appeared to him on his journey and had thereby introduced him to a happy new life.

The real problem with the 1848 staged production of Griseldis was that, in at least two important respects, it was somewhat unbalanced. In the first place, in spite of Elfrid’s centrality to the story and the fact that he was on stage for virtually the whole ballet, the choreographer Joseph Mazilier actually gave the dancer Lucien Petipa very little to do. As Ivor Guest points out (The ballet of the Second Empire [London, 1955], p. 37) he was only allocated a single pas and was subsequently much criticised for his (understandably) bored demeanour during the rest of the show. Secondly, some potentially spectacular episodes, including a hunt and a fête des jardinières, were not only poorly executed but were all concentrated together in the fourth tableau, leaving much of the rest of the production looking rather penny plain. It proved impossible to save the day even when, in something of a coup de théâtre, Ms Grisi rode a horse onto the stage (“A première danseuse on horseback!”, exclaimed one excitedly over-the-top commentator, “What temerity! What impudent daring!… Suppose that the noble animal that then carried the Opéra and its fortune had fallen or stumbled! God protect France!” [ibid., p. 35]). Ultimately, the outbreak of revolution in the French capital just a week into its run of performances proved to be the straw that broke the camel’s back. Griseldis disappeared off the stage and into the history books – though it sometimes failed to find a place even there, for it was included in neither Cyril W. Beaumont’s magisterial, if evidently misnamed, Complete book of ballets [London, 1937] nor any of its later supplementary volumes.

Getting on for a couple of centuries later, this new CD release gives us the opportunity to hear the music in isolation. Even if, sadly, we are thereby deprived of the delectable opportunity of seeing a prima ballerina kitted out for the 2.30 at Aintree, those aforementioned negative considerations that we might have had to consider if we had watched a danced performance of the ballet need no longer bother us. Faced simply with the score, we can assess it on its own, purely musical terms. Quite fortuitously, doing so has become a much easier – and more interesting – exercise than it might have been in the past because some relatively recent recordings of other Adam ballets now allow us to weigh up Griseldis not simply in isolation but in a somewhat broader context. Indeed, no less than seven of Adam’s 14 dance scores can now be easily accessed. Richard Bonynge has given us not only the best recorded performance of Giselle (Decca 478 3625), including several passages rarely if ever heard elsewhere, but also Le diable à quatre (Decca Eloquence 482 8603) and Le corsaire (Decca Eloquence 482 8605). Meanwhile, Andrew Mogrelia has introduced listeners to La jolie fille de Gand (Marco Polo 8.223772-73 or Naxos 8.574342-43) and La filleule des fees (Marco Polo 8.223734-35 or Naxos 8.574302-03). The latest conductor with a passion for bringing previously little-known Adam ballets to our attention is Dario Salvi. My colleague Raymond J. Walker welcomed his Orfa (Naxos 8.574478) to the catalogue just a couple of years ago and now Mr Salvi, who produced his own new edition of the Griseldis score in 2021, has recorded the latter with such evident enthusiasm that one can only hope that other releases may follow in due course.

Although the CD’s rear-cover blurb makes the bold claim that “Griseldis is one of Adam’s most important ballets”, its specific claims to greatness remain largely unelaborated in Robert Ignatius Letellier’s useful booklet note which instead emphasises the hitherto generally-overlooked broader significance of Adam’s ballet scores as a whole. The composer, it claims, “decisively influenced the development of the musical theatre of the 19th century, his work marking the first highpoint of the Romantic ballet. His 14 dance scores were… reflective of… [the] transformation to a new type of more substantial, symphonic and formally complex score that found its most familiar expression in the works of Léo Delibes, Ludwig Minkus, Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky and Alexander Glazunov”.

That proposition, it’s worth emphasising, marks an important change in how 19th century ballet history is perceived. It has traditionally been accepted that dance was in the musical doldrums until the advent of the transitional figure of Delibes, who was then followed by Tchaikovsky, a revolutionary who introduced “symphonic” elements and greater musical sophistication into ballet scores. Perhaps, as suggested here, the exhumation of such long-overlooked works as Griseldis, Orfa and others will see Adam re-evaluated in due course as an equally important and innovative figure? [Incidentally, it is also good to see the long-underestimated Ludwig Minkus now promoted to the major league – but that’s hardly surprising as we already know that Mr Letellier, who has written the definitive study of the composer’s work, is a staunch admirer.]

What, then, does Griseldis sound like? Well, the first thing to say is that it doesn’t, to my ears at least, sound anything much like Tchaikovsky or Glazunov. I can, however, detect a strong stylistic relationship with both Delibes and Minkus and, especially, with their early collaborative ballet La source. Auber – and especially his Marco Spada – also came to mind a few times, especially so in the first tableau’s pas de trois and the fourth tableau’s Après la valse: allegro. Professional musicologist Mr Letellier enthusiastically lists such striking features in the Griseldis score as “imaginative richness… vitality… [a] sure symphonic sense of structure, melodic fecundity and striking instrumentation…” As a general listener, I am in some doubt as to whether I would describe Adam’s score as “symphonic” in the same way that that word is applied to Tchaikovsky’s ballets. There is, nevertheless, a boldness, an ambition and a self-evident confidence in the deployment of orchestral resources that marks Griseldis out from the crowd. Aside from that, its most attractive features are those that were immediately spotted by those contemporary reviewers – consistent and attractive tunefulness and aptness for dance. Presented with the outline of the story in the accompanying booklet, it is quite easy to follow the way in which the music underpins and supports the on-stage action. Moreover, the strong rhythms, vivid colours and melodic precision of Adam’s score will allow anyone familiar with staged ballet performances to envisage imaginary choreography appropriate to that era. This is, then, really splendid stuff and an altogether delightful discovery. Interestingly enough, however, you may not appreciate Griseldis on your very first hearing. That’s because this turns out to be one of those occasionally-encountered recordings in which the performance’s colour and drama are both significantly enhanced by tweaking up the volume just a bit higher than usual on your CD player, whereupon everything makes much more impact, not just sonically but somehow, as if by magic, musically too.

The project of making the world premiere recording of Griseldis has, it seems, been something of a labour of love, not only for conductor Dario Salvi but also for his collaborators Mr Letellier, who, as already noted, is an authority on the composer, and Jean-Guillaume Bart who, as you will already know if you’ve clicked on the link above, choreographed the Paris Opéra-Ballet’s production of the aforementioned Delibes/Minkus La source.

Anyone who has followed Mr Salvi’s series of recordings on the Naxos label over the past few years will know that, even when recording his ongoing series of discs of Auber’s orchestral music, he has been known to chop and change orchestras. On this occasion he leads the Sofia Philharmonic and its musicians play the score with a degree of vigour and panache that suggests they were born to it (which they certainly weren’t, for no-one travelling, like the prince, from Bohemia to Moldova would make an unnecessarily long detour through Bulgaria). The Sofia PO Chorus has little to do – but does it, nevertheless, with commitment and skill. Meanwhile, the Serbian soprano Ms Jelić makes a positive impression. She gets to sing a rather moving little song, given an ethereal touch by its harmonium accompaniment, which is first heard in the second tableau. Adam brings the melody back in the final, fifth tableau, both in purely orchestral form in a romantic pas final: maestoso and twice more in an abbreviated vocal version as the ballet comes to its very end. He clearly – and rightly – thought it a good tune. Rather beautiful and touching in its simplicity and sentiment (“I am the secret voice, the voice that comes from heaven…”), it indeed brings to mind one of his most famous and beloved compositions, the Cantique de Noël.

The quality of the Naxos recording is clear and transparent throughout both discs, allowing us to hear plenty of the delightful inner felicities of Adam’s expert scoring.

It is, then, altogether a real pleasure to welcome this important and very enjoyable CD to the slowly but steadily growing number of performances of Adam’s ballets on disc. I strongly suspect that I will not be alone in reiterating with the greatest pleasure the words of that contemporary critic: “What lovely tunes! What zest! What coquetry! What vivacity!”

Rob Maynard

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.