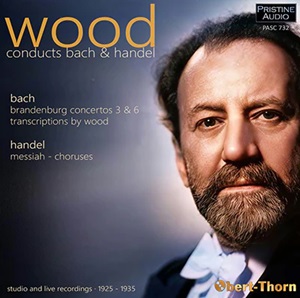

Wood conducts Bach and Handel

Brandenburg Concertos Nos 3 and 6

Suite No. 6 (arr. Wood)

Transcriptions by Wood

Handel Messiah choruses

Orchestras and chorus/Sir Henry Wood

rec. 1925-1935, London, UK

Pristine Audio PASC 732 [76]

Sir Henry Wood, as even those who have no interest whatever in historical recordings would know, was one of the most important British performing musicians of the 20th century. His advocacy of all sorts of music, especially the British and avant garde music of his time, and his foundation of the annual Promenade concerts which still bear his name, have assured him of a recognition among modern concert goers which very few performers who have been dead for eighty years can boast. It is therefore sad that in his time he was regarded by many as not much more than a musical workhorse – incredibly valuable, but not of any great inherent quality or interest. This was reflected by the record companies. He recorded quite prolifically for Columbia from 1915, conducting many first recordings of standard repertoire pieces (though often cut, sometimes savagely), until the advent of electrical recording in 1925. At this point many bigger-name maestros who had been reluctant to record by the acoustic process became available, and Wood was unceremoniously pushed to one side by 1928. He made some recordings (a number of which are on this CD) in the early to mid ’30s, but it was only when he was taken up by Decca in 1935 that he recorded major works again. But this was a short-lived return, lasting only until 1937, and he returned to Columbia for two last recordings: the Serenade for Music composed by Vaughan Williams in 1938 for the 50th anniversary of Wood’s conducting debut, and in 1939 for his own Fantasia on British Sea Songs which was – and still, to some extent, is – a Proms favourite.

The recordings on this CD span the decade of his recording decline, and, to my ears, demonstrate the unfairness of it. The performances here are undoubtedly not what we expect to hear in this repertoire today, but that merely demonstrates the change in musical fashion, not the exposing of the evils of previous performance practices.

We begin with the two Brandenburg Concertos which are for strings only. The first movement of No. 3 will probably surprise those who expect all early recordings of baroque music to be slow and heavy handed. Although the number of strings involved is several times what we would now expect, the tempo is sprightly and the articulation crisp, with inner voices picked out in an interesting way at times (e.g. at one minute into the first movement). There is a delightful ebb and flow of dynamics with little of the sort of slowing down at cadences which Furtwängler uses in his almost contemporaneous recording with the BPO. The variety of articulation, from almost spiccato to long-breathed legato is a very pleasing. There is also, rather surprisingly, barely a hint of portamento in either of the concertos. The transition between the two movements is merely two sustained chords and the same sprightly atmosphere is maintained throughout the second movement. I enjoyed this performance very much, and the early Abbey Road recording is excellent for its day.

In the sixth concerto, the tempo is again not at all slow, though the feeling is much more trenchant, with a more consistently sustained legato, but this does not in any vitiate the fine momentum. I particularly like the crescendo-decrescendo arc of the phrasing of the main theme. The second movement is marked “Adagio, ma non troppo”, and we might expect a very slow performance, but the tempo is quite swift, though unsurprisingly the articulation is legato throughout. To my ears, it never sags because of the constantly imaginative dynamic variety. Rubato is present but by no stretch is it excessive. The third movement is a very muscular, outdoors performance, the rapid scale passages alternating between different strings groups reminding me of playground high jinks. There is, given the comparatively slight use of rubato, a surprisingly protracted allargando at 2.54 into the movement, which I don’t find particularly convincing. Both of the Brandenburgs are a country mile from what we expect today, but I find them very satisfying on their own terms.

The Suite No. 6 is the only acoustic recording on this CD. I find this title rather confusing – did Wood make five earlier Bach suite arrangements? Was it intended as a sort of addendum to Bach’s four (which would mean there must be a Wood fifth)? The title clearly came from the original 78s, whose labels call it “Suite No. 6 for Full Orchestra”. It had the great misfortune of being recorded only a couple of months before electrical recording was initiated by Columbia, so had less than two years in the catalogue, being deleted in the Great Cull of acoustic recordings in February 1928. I’m very grateful to Pristine for identifying all the pieces which Wood used in this suite. I have had the 78s for a long time, and had always intended to try to do so, but had never got round to it. The plunge in recording quality between the Brandenburgs and the suite is almost shocking, and demonstrates again that the change from acoustic to electric recording was the greatest single advance in recorded sound; none of the subsequent advances made remotely the same difference to the basic quality of the sound. Wood’s orchestrations never had the imagination and refinement of Beecham’s Handel or the flair and panache of Stokowski’s Bach arrangements, and those to be found on this CD are enjoyable, but a little crude. The playing of the New Queen’s Hall Orchestra is very fine, the woodwind especially have real flair, and again there is almost no string portamento. The suite is enjoyable, but it doesn’t approach the glorious re-imagining of Beecham’s Love in Bath Handel ballet.

The electrical performances of the Gavotte , Air and Preludio which follow the Suite are expressive and agile with plenty of variety of articulation, though cadences, especially final ones, tend to be heavier than in the other recordings on this CD. Unsurprisingly, there is an amount of portamento to be heard in the “Air on the G String” to be found nowhere else here. It is a good performance, but cannot stand comparison with the contemporaneous Furtwängler/BPO one. The Prelude goes with tremendous vigour and élan, and the strings of the QHA are excellent. The Toccata and Fugue also has plenty of vim, but it is cruder than Stokowski’s orchestration. In the final one of the introductory flourishes there is even what sounds like the clang of an anvil, which is more Hollywood than even Stoki would have countenanced. The glockenspiel also hits you right between the eyes on a couple of occasions, though that is probably more the fault of the recording balance than Wood’s use of t. The overall quality of this recording is actually very good indeed for a Decca recording of 1935; this was long, long before Decca had a reputation for outstanding sound quality.

The final five items consist of the first complete reissue of all the published recordings taken live at the 1926 Crystal Palace Handel Festival. That these were recorded was a tremendous piece of both luck and chutzpah. The luck comes in because the Triennial Festival had taken place since 1862, and this was the last time it was held. Electrical recording was adopted by Columbia just over a year before the 1926 festival, so the stars came into alignment by the purest chance. The chutzpah is self-evident: using a brand new technology to record forces of this immensity (a choir and orchestra numbering 3500) in an acoustic as intractable as that of the Crystal Palace with no opportunity to make test recordings with a full audience present would give a recording engineer nightmares even today. The fact that the turntable engineers had no visual contact with the musicians added to the problems and explains why “And the glory of the Lord” has its first note clipped and the last notes of “Behold the Lamb of God” are missing. This last omission may have been caused by a wish to avoid applause after a particularly contemplative chorus; one of the surprising things shown by these recording is that every single item was apparently applauded. Possibly as a result of the problems with this recording, Columbia pretty well gave up on live recordings, whereas HMV made a considerable number right up until 1929. However, they similarly had a low scoring rate of issuable recordings and gave up until 1936, when a large number of live recordings were made at Covent Garden, though these had an even poorer number of issued sides.

I feel very ambivalent about these sides. While it is wonderful to be able to experience, in however limited a way, one of the great musical events of the late 19th century, it cannot be argued that the performances are remotely satisfactory. Forty years before this performance, George Bernard Shaw was railing against their absurdity, and he let fly with both barrels in 1893, calling them “laughably dull, stupid, and anti-Handelian… these choral monstrosities”, and it is difficult to disagree with this as a reaction to these performances. The root of the problem, of course, is precisely the thing that most people at the time specifically went to the performances to experience: the sheer size of them. But this meant that no tempo could be faster than a leisurely andante, dynamic variety was almost impossible to impose, and ensemble could never be more than approximate. No conductor, not even one as experienced as Wood in performing wonders with minimal rehearsal, could truly conduct such forces; all he could do was direct the traffic and pray that there were no fatal accidents. These sides are a fascinating historical survival, but no real musical pleasure can be gleaned from them.

The quality of Mark Obert-Thorn’s transfers is as excellent as always. He brings the sound forward and into perspective, removing almost all the surface noise without dimming the high frequencies.

It would be easy to dismiss these recordings as entirely past their sell-by date, as mere curiosities of musico-archaeological interest, but I would disagree with this entirely. The more I think about it, the more convinced I am that there is no such thing as progress in the scientific sense in terms of performance style. Each generation performs in a style which speaks to its own audience – and this is entirely as it should be. Only the sort of fool who thinks that every performer in the past was little more than a naïve fool, waiting to be shown how it should be done by the present generation, would simply dismiss these performances – not thinking, of course, that another fool seventy years hence would dismiss their idols in just the same way. Unless you are arc-welded to the precepts of today’s HIP practitioners, give this CD a try; you may find much more to enjoy that you expect.

Paul Steinson

Previous review: Jonathan Woolf (February 2025)

Availability: Pristine Classical

Contents

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 in G, BWV 1048

British Symphony Orchestra/Sir Henry J. Wood

Recorded 16 June 1932 in Abbey Road Studio No. 1, London ∙ Matrices: CAX 6439-2 & 6440-1 First issued on Columbia LX 173

Brandenburg Concerto No. 6 in B flat, BWV 1051

Symphony Orchestra/Sir Henry J. Wood

Recorded 12 June 1930 in Central Hall, Westminster ∙ Matrices: WAX 5617-2, 5618-2, 5619-1 & 5620-1 ∙ First issued on Columbia LX 41/2

(arr. Wood) Suite No. 6 for Orchestra

Prelude (Prelude No. 3 in C sharp from Well-Tempered Clavier Book I, BWV 848)

Lament (Capriccio on the departure of a beloved brother, BWV 992)

Scherzo (Scherzo from Partita No. 3 in A minor, BWV 827)

Gavotte & Musette (Gavottes I & II from English Suite No. 6 in D minor, BWV 811)

Andante mistico (Prelude No. 22 in B flat minor, BWV 867)

Finale (Preludio from Partita for Violin solo No. 3 in E, BWV 1006)

New Queen’s Hall Orchestra/Sir Henry J. Wood

Recorded 5 February 1925 in the Clerkenwell Road Studios, London ∙ Matrices: AX 909-2, 910-2, 911-1 & 912-1 ∙ First issued on Columbia L 1684/5

(arr. Wood) Gavotte (from Partita No. 3 in E, BWV 1006)

British Symphony Orchestra/Sir Henry J. Wood

Recorded 16 June 1932 in Abbey Road Studio No. 1, London ∙ Matrix: CAX 6442-2 ∙ First issued on Columbia LX 173

(arr. Wilhelmj-Wood) Air on the G String (from Suite No. 3 in D, BWV 1068)

British Symphony Orchestra/Sir Henry J. Wood

Recorded 16 June 1932 in Abbey Road Studio No. 1, London ∙ Matrix: CAX 6441-1 ∙ First issued on Columbia LX 173

(arr. Wood) Preludio (from Partita No. 3 in E, BWV 1006)

New Queen’s Hall Orchestra/Sir Henry J. Wood

Recorded 19 June 1929 in Central Hall, Westminster ∙ Matrix: WAX 5031-4 ∙ First issued on Columbia L 2335

(arr. Wood) Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV 565

Queen’s Hall Orchestra/Sir Henry J. Wood

Recorded 2 May 1935 in the Thames Street Studio, London ∙ Matrices: TA 1781-2 & 1782-3 ∙ First issued on Decca K 768

George Frideric Handel (1685-1759)

Messiah, HWV 56

No. 4, “And the glory of the Lord”

No. 22, “Behold the Lamb of God”

No. 28, “He trusted in God that he would deliver him”

No. 33, “Lift up your heads, O ye gates”

No. 41, “Let us break their bonds asunder”

Handel Festival Choir and Orchestra/Sir Henry J. Wood

Recorded 12 June 1926 in the Crystal Palace, London ∙ Matrices: WAX 1595 (Track 17), 1597 (18), 1599 (19); WA 3413/4 (20); and WAX 1600 (21), all Take 1 ∙ First issued on Columbia L 1768/9 (17-19, 21) & D 1550 (20)