Piotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

Swan lake – ballet in four Acts (1875-1876)

Choreography by Marius Petipa, Lev Ivanov

Additional choreography by Liam Scarlett and Frederick Ashton

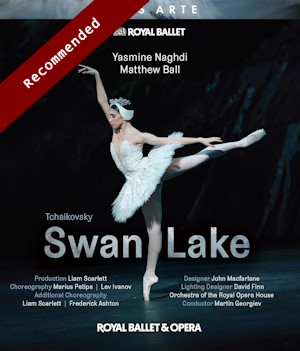

Odette/Odile – Yasmine Naghdi

Prince Siegfried – Matthew Ball

The Royal Ballet

Orchestra of the Royal Opera House/Martin Georgiev

rec. 2024, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London, UK

Opus Arte OABD7326D Blu-ray [151]

Each of Tchaikovsky’s full-length ballets occupies a distinct place in the world of classical dance. The sleeping beauty is generally acknowledged as posing the supreme artistic challenge for any company. The nutcracker, on the other hand,is the ever-reliable cash cow, with its Christmas-season full houses serving to subsidise other, less popular productions mounted during the rest of the year. Meanwhile, Swan lake enjoys a quasi-symbolic status as the public face of the whole art form, for the white-tutued members of the corps de ballet have come to epitomise the concept of classical dance to the man in the street who might well run a mile if offered a ticket to see the real thing.

Strikingly contrasted as they are, all three pieces firmly maintain their places as mainstays of the classical ballet repertoire and all feature regularly in the programmes of companies that aspire to establish or to maintain worldwide reputations.

Putting aside various modern re-imaginings of the piece – of which Jean-Christophe Maillot’s Lac (opus Arte DVD OA 1148 D) is probably the most artistically interesting and Matthew Bourne’s crowd-pleasing reworking the most commercially successful – the discerning collector of Swan lake on Blu-ray disc or DVD is quite spoiled for choice. While my own collection is by no means an exhaustive one, it currently includes eight different performances of the ballet on Blu-ray and a further ten on DVD. No doubt it will expand even further as more discs are released in the future.

As I have frequently pointed out, London’s Royal Ballet is, I think, unique in continuing to film and release many of its performances. As you’d certainly expect, those include brand new additions to the company’s repertoire as well as new productions of old favourites. However, perhaps surprisingly in these economically straitened times, they also include current productions that have been re-filmed so as to showcase new casts. Thus, while this new Blu-ray disc gives us the same production and design that featured on a previous 2019 Royal Ballet release (OA BD7256 D), it replaces the latter’s star dancers Marianela Nuñez and Vadim Muntagirov with Yasmine Naghdi and Matthew Ball. As well as those two releases, I will also consider, in passing, two other Royal Ballet Swan lake performances that many collectors may already own on Blu-ray. The first, filmed in 2009, is headlined by Marianela Nuñez and Thiago Soares and is available as part of a competitively-priced three-disc set Tchaikovsky – The classic ballets (OA BD7131). The second dates from 2015 and stars Natalia Osipova and Matthew Golding (OA BD7174 D).

Given the Royal Ballet’s enterprisingly wide-ranging repertoire and the quality of both its productions and the artists it attracts – just consider how many of each year’s Prix de Lausanne scholarship winners choose to pursue their careers in London – it is not surprising that many expert critics now consider it to be the world’s greatest dance company. As a consequence, there is, in all honesty, little to choose between the technical abilities of all the Covent Garden artists under consideration in the four Swan lakesalready mentioned. Each of the star combinations – Nuñez/Soares, Osipova/Golding, Nuñez/Muntagirov and Naghdi/Ball – are unquestionably world class. Any differences between them tend to result from individual dancers’ personalities and the way in which they approach and interpret their roles. Admirers of Ms Nuñez, for example, will certainly cherish her invariably displayed grace, elegance and self-evident good nature – all wonderfully deployed in her exquisite portrayal of the white swan Odette. Ms Osipova’s many fans, on the other hand, will no doubt appreciate the spontaneity, playful humour, risk-taking physicality and sheer charisma that she brings to the role of the malevolent black swan Odile. While the keenest balletomanes will no doubt spend many happy hours combing through the finest distinctions between the four pairs of dancers, the general collector ought to be quite happy with any of them.

In fact, the most striking dividing line between these four Covent Garden performances lies in the elements of production, design and choreography. In those respects, they fall into two distinct camps.

In the first are the 2009/Nuñez/Soares and 2015/Osipova/Golding versions. Both are based on a 1987 production by Anthony Dowell, featuring designs by Yolanda Sonnabend. Its choreography is attributed to Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov, with additional contributions from Frederick Ashton and David Bintley.

In the second are the 2019/Nuñez/Muntagirov and 2024/Naghdi/Ball performances. Both of those showcase a radically new production of Swan lake, produced by Liam Scarlett and designed by John Macfarlane, that had replaced the older Dowell production in 2018. New choreography had also been introduced that year, described at the time – and specifically confirmed in print on the back cover of the 2019 DVD – as being by Liam Scarlett, after Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov, with additional input by Frederick Ashton. That is certainly how critics and balletomanes have described this Swan lake ever since. However, an intriguing inconsistency has now arisen, for the rear cover of the 2024 performance credits the choreography to Petipa and Ivanov – with Scarlett now joining Ashton as merely a provider of “additional” choreography.

Opus Arte uses such small print and dark colours on the back of its releases that the newly revised attribution is easily missed – and the somewhat skimpier than usual booklet documentation offers no explanation whatsoever for the change. Moreover, I cannot see any immediately obvious choreographic differences between the 2019 and 2024 performances. An obvious line of speculation, in the absence of any other information, might be that the apparent downgrading of Mr Scarlett’s artistic role has been precipitated by the allegations of sexual misconduct that abruptly destroyed his career in 2019, just two years before his early death. If that is the case – and if the Royal Ballet’s choreographic history is now being rewritten on such a subjective basis – it is nothing less than disgraceful.

If unanticipated confusion now exists regarding Liam Scarlett’s role in the choreography of the new 2018 Swan lake, no-one yet, thank goodness, seems to be questioning his overall responsibility for the production as a whole. And what a beautifully conceived one it is! As I can confirm from my own visits to the Royal Opera House, when first revealed, some of its most striking features – the John Macfarlane-designed sets and costumes for Acts 1 and, especially, 3 – draw well-deserved gasps of admiration from audiences.

Other dance companies often place the first Act in little more than a generalised “outdoors” setting, with a bare stage, featuring next to nothing in the way of pieces of scenery, representing a field and a blue backdrop representing a clear sky. The 2024 Covent Garden production, on the other hand, incorporates an enormous amount of physical detail, both large and small, that immediately and successfully conveys the sheer opulence of the royal court and its courtiers and thereby dramatically enhances the storytelling. Dominating the stage, the massive gateway to the royal palace, through which characters make their entrances and exits, allows us subconsciously to infer that the prince is happiest as a cultural outsider. His mother the queen, on the other hand, emerges only momentarily into this “real” world before retreating back into the luxurious artificiality of palace life and her own comfort zone.

If the impressive palace gateway dominates the stage in the first Act, its Act 3 equivalent is a dais, topped by the royal throne and backed by a massive decorative wall of exquisitely-lit burnished gold, altogether one of the most impressive sets I’ve seen at the Royal Opera House. Just as striking is a massive staircase that descends to the rear of the stage and allows a large cast of home-grown courtiers, along with visiting Spaniards, Hungarians, Italians, Poles and assorted gold-digging princesses, to enter in dramatic and appropriately flashy fashion. In one really novel but effective feature, in the Act’s climactic final moments a flock of black swans also rushes onstage to add to the mayhem, though, with their birdy feet presumably unable to manage a flight of steps, they rather prefer, it seems, to swoop in from the wings.

Anyone familiar with Russian history and culture will be able to pick out plenty of obvious and not-so-obvious references in all this. The court itself might almost be a replica, at times, of that of the last tsar, Nicholas II, while the queen, dressed as if at the opulent height of Edwardian fashion, is something of a doppelganger for his misguided and ill-fated wife Tsarina Alexandra. The odd bit of anachronistic medievalism in the Act 3 courtiers’ costumes is easily explained in such a context, for the real-life Nicholas and Alexandra loved to stage palace functions at which everyone was required to dress up as their distant forebears. Admirers of Russian cinema will also spot more than a few particularly grotesque characters who look like they’ve stepped right out of an audition for a part in Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible or Alexander Nevsky. It’s gorgeously over the top, visually lush and all rather beautiful.

This production’s Acts 2 and 4 – the “white” Acts – are set in a starker, sparer landscape that appropriately discards all the artificiality and surface glitter of court life and takes us back to a world of simple, straightforward concepts. Both Love and Loyalty are to be found here, of course, but so is Evil – displayed absolutely overtly rather than in the subtler and (literally) disguised manner exhibited at the royal court. Reviewing this new release’s original cinema transmission, my colleague Jim Pritchard was less than impressed by the lakeside set that’s common to both Acts, observing that “all we see is a dingy backcloth and the suggestion of a jagged black rock”. The difference between Jim’s reaction and my own may have a simple technical explanation, such as that the experience of watching the production on a wide cinema screen gives a different overall impression from watching it on a domestic television set. I suspect, however, that our different opinions are simply subjective and that one man’s “dingy” is another man’s “darkly mysterious”. The white Acts’ sets certainly offer a massive contrast to the exquisite and well-lit level of detail that we see in Acts 1 and 3, but that’s surely a deliberate producer’s decision. Perhaps the differences are meant to suggest a Manichean physical and moral division between the two worlds of the superficial, heartless court and the lakeside, even if both are, in their own ways, characterised by degeneracy and fetid corruption.

I made reference earlier to the fact that the lead dancers in all four Royal Ballet versions under consideration are first class technicians and that there is almost nothing, in that particular respect, to choose between them. However, I also pointed out that they give their own distinctive performances. Yasmine Naghdi’s most striking feature in the role of Odette is, perhaps, a sense of ineffable sadness that’s so convincing that you’d surely swear that despondent dolour must be her natural default disposition. Her artistic versatility is made quite apparent, however, by a third Act portrayal of Odile that, as she revels in sheer over-the-top nastiness, is quite up there with that of Natalia Osipova or even the great Maya Plisetskaya. Ms Naghdi’s performance combines the highest quality dancing – I was particularly struck by the expressive fluidity of her arms – with the ability to act her role (or, in this particular case, roles) in a fully committed manner.

It’s worth pointing out, incidentally, that, as a company that’s notably strong in the presentation of full-length narrative works, the Royal Ballet appears to put more effort than most into coaching its dancers to be convincing actors. Thus, Matthew Ball, as the troubled prince, makes as strong an impression with his facial expressions as he does with his very impressive jumps and the sensitive and considerate way in which he partners Ms Naghdi. In one of this release’s extra features, Cast and creatives discuss Swan lake, Mr Ball explains that it’s important to him to find an individual and personal interpretation for any role and certainly, on this occasion, his take on the prince’s character differs significantly from that of his 2019 predecessor Vadim Muntagirov. Whereas the latter had portrayed the prince as rather shy, diffident and somewhat easily intimidated, Ball gives the same character a significantly more macho persona, so that, when confronted with Rothbart’s machinations, he appears just as likely to launch a hefty uppercut as to slink off abashed into a corner.

Other members of the company are also worth special mention. Taking the part of the prince’s friend and confidant Benno, Joonhyuk Jun exhibits both superb athleticism and sensitivity to his role and justifiably becomes, if curtain call applause is any guide, one of the audience’s favourites. Similarly, Leticia Dias and Annette Buvoli take full advantage of the way in which Liam Scarlett has beefed up the role of the prince’s sisters and manage to make rounded characters out of them. Scarlett has also expanded Rothbart’s role. No longer is he simply the waterside wizard who has bewitched a host of girls into a flock of swans. Instead he has also become the queen’s eminence grise – the tsarina’s Rasputin, if you like – who is determined to undermine the prince’s position at every opportunity and, ultimately, to seize the throne for himself. Unfortunately, as Jim Pritchard has also pointed out, the way in which Rothbart’s two manifestations cohere is never properly explained. I imagine that if Liam Scarlett had not died prematurely, that issue is one that he might have returned to address. In the meantime, it wouldn’t be a bad idea for Covent Garden to adopt Jim’s excellent suggestion that, at the moment of his Act 4 death, the point that swampy-Rothbart and courtier-Rothbart are actually one and the same person could be visually hammered home by some sort of on-stage transmogrification of one into the other (presumably quite a straightforward technical operation in that aforementioned dingy/darkly-mysterious lighting). In spite of the essentially flawed nature of the role as it currently exists, dancer Thomas Whitehead gives a most compelling performance.

I do hope, by the way, that in praising these artists I’m not about to bring their careers to a premature end. I write that because in the 2009/Nuñez/Soares, 2015/Osipova/Golding and 2019/Nuñez/Muntagirov performances the role of the queen (actually cast-listed more traditionally in the first two as merely a princess) had been taken by Elizabeth McGorian. No sooner had I given this great Royal Ballet grande dame a few sentences of well-deserved and overdue praise in a recent review than, lo and behold, the new 2024/Naghdi/Ball performance arrives with a new dancer replacing her as Swan lake queen. I can award no higher praise than to say that Christina Arestis is just as stately and regally aloof as her predecessor – and it will no doubt be merely a matter of time before, at the end of Act 3, she matches Ms McGorian’s perfectly timed and beautifully executed swoon to the floor as her court collapses in utter disarray all around her.

This performance boasts two other names I had not encountered previously. The British-Bulgarian conductor Martin Georgiev delivers a strongly dramatic performance of the score while always remaining sensitive to the practical requirements of the dancers on stage. As you would expect, the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House responds expertly and idiomatically to his leadership. The second new name is that of video director Peter Jones. That role has usually been taken in the past by the experienced Ross MacGibbon, but a little online research demonstrates that Mr Jones is an experienced fellow when it comes to filming ballet and opera productions, so I think we can assume that we are in equally safe hands. I certainly found nothing to criticise – and, indeed, much to enjoy – in his work on this occasion. As a welcome added bonus, I found no instances on this release where the dreaded phenomenon of motion blur was any sort of issue.

There are two extra features included on this disc, although, as usual with Royal Ballet/Opus Arte releases, they are very brief and miss the opportunity to add greater value by probing a little more deeply. Amanda Hall and the costume team create a tutu for Swan lake shows us just that – and what a detailed, intricate process that proves to be. The aforementioned Cast and creatives discuss Swan lake delivers, as you might expect, plenty of predictably bland platitudes. In one respect, though, it’s rather more intriguing, for several of the interviewees stress the importance of Liam Scarlett’s work – though that’s as the creator of the overall production rather than specifically as its choreographer.

I’m now beginning to think that I’ve missed some official Royal Ballet diktat that’s changed the way in which the late Mr Scarlett may be described. Even so, I’ll risk imprisonment in the cells of the old Bow Street Magistrates’ Court, just down the road from the Royal Opera House, and say that his achievement as both choreographer and producer makes this the most enjoyable version of Swan lake that’s currently available on Blu-ray and DVD. Moreover, thanks to the charismatic pairing of Naghdi and Ball, this version just displaces its 2019/Nuñez/Muntagirov predecessor as the performance you ought to acquire, especially if you want to appreciate why this ballet is, as it turns out, much more than simply the public face of the whole art form.

Rob Maynard

Other cast and production staff

Von Rothbart – Thomas Whitehead

The queen – Christina Arestis

Benno – Joonhyuk Jun

Prince Siegfried’s sisters – Leticia Dias and Annette Buvoli

Waltz and polonaise – Mica Bradbury, Chisato Katsura, Charlotte Tonkinson, Lara Turk, Luca Acri, David Donnelly, Téo Dubreuil, Benjamin Ella and Artists of the Royal Ballet

Cygnets – Mica Bradbury, Ashley Dean, Sae Maeda and Yu Hang

Two swans – Hannah Grennell and Olivia Cowley

Spanish princess – Yu Hang

Hungarian princess – Mica Bradbury

Italian princess – Sae Maeda

Polish princess – Chisato Katsura

Spanish dance – Nadia Mullova-Barley, David Donnelly, Benjamin Ella, Harrison Lee and Aiden O’Brien

Czárdás – Katharina Nikelski, Kevin Emerton, Sierra Glasheen, Viola Pantuso, Charlotte Tonkinson, Marianna Tsembenhoi, Daichi Ikarashi, Joshua Junker, James Large and Marco Masciari

Neapolitan dance – Isabella Gasparini and Leo Dixon

Mazurka – Julia Roscoe, Giacomo Rovero, Oliva Findlay, Madison Pritchard, Lukas B. Brændsrød and Téo Dubreuil

Artists of the Royal Ballet and students of the Royal Ballet School

Production by Liam Scarlett

Design by John Macfarlane

Lighting design by David Finn

Staging by Gary Avis, Laura Morera and Samantha Raine

Directed for the screen by Peter Jones

Technical details

1080i High Definition Blu-ray disc

Audio formats: LPCM 2.0 and 5.1 DTS-HD 96kHz Master Audio surround

All regions

Subtitles for extra features in English, French, German, Japanese and Korean

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free