Dmitry Shostakovich (1906 – 1975)

Symphony no. 8 in C minor, op. 65

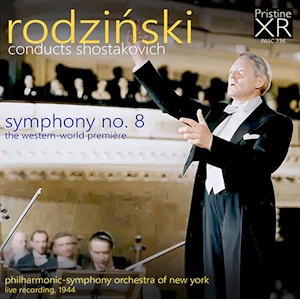

Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra of New York/Artur Rodziński

rec. April 1944, Carnegie Hall, New York

Pristine Audio PASC736 [66]

The final stages of World War II have been very much on our minds this week here in Great Britain as we commemorate VE Day, so this recording of the April 1944 American première of Shostakovich’s Eighth Symphony has, in addition to its historical importance, a certain poignancy.

The conductor Artur Rodziński was born in Croatia in 1892. His family was Polish, and he studied music in Lwów, Poland, where he began his conducting career. In 1925, Leopold Stokowski invited him to Philadelphia as his assistant, which he combined with teaching at the famed Curtis Institute. He was quickly recognised as a superb trainer of orchestras, and became conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic in 1927, followed by the Cleveland Orchestra in 1933.

His appointment as music director of the Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra of New York – or, as we know it better, the New York Philharmonic – took place in 1943, succeeding John Barbirolli, and he stayed with them until 1947. Those were somewhat turbulent years; Rodziński, who could be difficult and dictatorial, had major struggles with the management, and handed in his resignation in 1947, before going off to conduct the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. His concerts with the Philharmonic, however, had been widely regarded as brilliantly successful.

We shouldn’t underestimate the severe challenges of presenting this symphony, which had been premiered in Moscow only a few months earlier. The score of the previous symphony, the celebrated ‘Leningrad’, had famously been smuggled out of Russia on microfilm before being flown to America for its première. The story of No. 8 is less dramatic, but the Columbia Broadcasting System seems to have paid some $10,000 to the Russian publishers for permission to transmit the concert – a huge sum in those days.

Rodziński was an important interpreter of Shostakovich’s music. He had conducted the American premières of the opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District in 1935 and the Fifth Symphony in 1938. The two men knew each other, and the sleeve-notes here reproduce the text of Shostakovich’s warm message to the conductor and his players before the concert.

The recording sounds remarkably good; in his notes, Andrew Rose, who was responsible for the re-mastering from the 78 rpm discs for Pristine, points out how well the original sound was captured on those discs. The final results are most pleasing, and can be listened to without the difficulty sometimes experienced with recordings of this vintage.

But what of the performance itself? The symphony has five movements, with an enormous opening Adagio, nearly thirty minutes in duration.This is shaped and sustained superbly by Rodziński, with some strikingly beautiful solo playing, in particular the immensely demanding cor anglais solo towards the end, as well as the cruelly exposed final trumpet entry. The tension built up in the central climax is as shattering as it needs to be, with the percussion faithfully captured. Rodziński secures such tremendous contrasts of dynamic all the way through, my only disappointment being that the orchestral basses haven’t fared as well as one might hope in the balancing of the sound – but this is a small carp when compared to the overall impact.

That huge movement is followed by three shorter ones: the second is burlesque and march-like, the other much more threatening. This third movement, in fact, is one of the composer’s most memorable images; desperate running crotchets in the violas, while the woodwind and trumpets interpolate phrases that drop like grenades. This is possibly the movement that gains most from a modern recording; the sense of growing panic needs more presence in the orchestral sound. Nevertheless, Rodziński and his orchestra still manage to convey its sinister character.

The conflagration that concludes the third movement also marks the beginning of the fourth, a deeply enigmatic piece in which, basically, nothing happens. It is music metaphorically twiddling its thumbs, waiting for something to come along, for something to occur. A vacuum it may be, yet Shostakovich paradoxically contrives to fill that vacuum with some wonderful textures in strings and woodwind. Indeed, as the fifth movement begins, something does happen, in the shape of a pathetic little dance in the bassoons, which is gradually taken up by various other instruments. There is finally a building sense of purpose; but that purpose serves only to bring a return of the cataclysmic climax from the first movement. The music recoils in horror, then fades away quietly.

All of this is vividly realised in Rodziński’s reading, and by his players. This finale is among the most notoriously difficult things Shostakovich wrote, drifting across the bar lines, with seemingly random entries of instrumental parts often at cross-purposes, or only tangentially related. I have no idea how long Rodziński had in order to study this incredibly involved score, or how much rehearsal time had been devoted to the symphony; not as much as he would have liked, I suspect, in either case, but he and his orchestra do a magnificent job, and the results are still very much worth hearing today.

Gwyn Parry-Jones

Availability: Pristine Classical