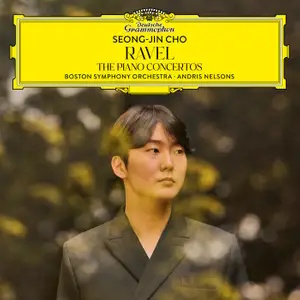

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937)

Concerto for piano and orchestra in G Major M83 (1931)

Concerto for the left hand for piano and orchestra in D Major M82 (1930)

Seong-Jin Cho (piano)

Boston Symphony Orchestra/Andris Nelsons

rec. 2023/24, Symphony Hall, Boston, USA

Deutsche Grammophon 4866820 [41]

Quite often it happens that I have a disc for review and before I’ve finished appraising it, we publish a review by a colleague. In such cases I do my very best to put their views out of my mind so that I approach the disc as independently as I can. On this occasion, though, a comment which Dominic Hartley made in his recent review of this present disc stuck with me. Dominic referred to “an unquestioned assumption by a lot of record companies that the Ravel concertos are generally best heard in the company of each other.” He went on to ask a very pertinent question: “what if you just want to put on a record and see where that takes you? Hearing either concerto with something different can be a revelatory experience.” I think there’s a lot in what Dominic says. He cites the pairing of the G major concerto with Prokofiev’s Third concerto on the superb 1984 DG disc by Marta Argerich and the LSO with Claudio Abbado. Other examples that spring to my mind are the classic 1957 recording of the same concerto by Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, on which the coupling was Rachmaninov’s Fourth concerto (review). More recently, Steven Osborne recorded both concertos for Hyperion and added Falla’s Noches en los jardines de España (review). The question is pertinent, not just on account of Dominic’s very fair musical point but also when one considers the playing time of this new disc. Quite frankly, forty-one minutes is distinctly short measure for a full-priced CD these days. I suppose, though, that DG have boxed themselves into a bit of a corner because Seong-Jin Cho has also recorded for them the solo piano music of Ravel and I understand that everything from that survey, including these two concertos, is being released as a three-disc set; I presume that will have limited DG’s ability to add to the contents of this disc.

I’ve not previously encountered the South Korean pianist Seong-Jin Cho but he’s clearly a formidably talented player. In both these concertos he exhibits virtuosity and brilliance in abundance. He also has the benefit of performing with Andris Nelsons and the Boston Symphony. I’ve experienced Nelsons as a concerto accompanist on a number of previous occasions, both on disc and also live in his days with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra; he’s usually excellent in this role and in these two concerto performances the contribution of the BSO is marvellous in all respects. As an example of the BSO’s excellence, try that magical orchestral passage, led off by the harp, in the first movement of the G major concerto (tr 1, 4:43-6:03). Here, the scoring shows Ravel at his most imaginative; the BSO play the episode wonderfully.

In the first movement of the G major concerto, the BSO matches Cho’s precision and brilliance; between them, the musicians and engineers achieve a fine degree of clarity. I admired Cho’s playing, which is, by turns, agile or poetic. A touchstone for me in any performance in this concerto is the miraculous passage (here, tr 1, from 6:31) where Ravel asks his pianist to play the melody in trills. The effect should be seamless, as both Michelangeli and Argerich achieve; Cho brings off the passage very well, though I’m not sure he quite matches Michelangeli in these bars. The great Italian’s recording is now nearly 70 years old and, frankly, it’s beginning to show its age but Michelangeli is so captivating in this concerto – especially in the poetic passages – that one tends to forget any limitations in the recording per se. Marta Argerich’s delivery of the trill passage is also very special, as is the way that she and Abbado deliver the music that leads up to it.

The second movement opens with an extended piano solo. Cho plays the music with grave beauty. I like his performance but the music seems to flow more naturally in Argerich’s hands; she combines grace and poetry in an ideal fashion. The movement culminates in a truly memorable passage where the cor anglais takes up the melody with which the pianist introduced the movement, against which the piano provides a stream of delicate filigree decoration. Cho and Nelsons do this very well (tr 2, 6:29 – 8:30), though there were one or two occasions when Cho’s playing came into the foreground more than I expected, slightly overwhelming the cor anglais tune. The BSO’s cor anglais player does a fine job – it would have been nice if he/she had been credited in the booklet. I have to say, though, that there’s even more refinement in the Argerich performance; she decorates the melody with consummate delicacy and the LSO’s cor anglais player is ideal (was it Christine Pendrill, I wonder?). Michelangeli offers what I might term ‘patrician poetry’ in this movement. However, here’s an example of the limitations of the EMI sound by comparison with more modern versions; as recorded, the sound of Michelangeli’s piano is not as pleasing and there’s something of a ‘twang’ on certain notes. That said, in his version the passage with the cor anglais is delivered with a lovely simplicity.

The finale could scarcely offer a greater contrast with the serene slow movement; here, Ravel allows everyone to have riotous fun. Both Cho and the members of the BSO take up the opportunity with alacrity – the orchestra has a ball! Cho’s athletic virtuosity is mightily impressive. The notes remind us of Ravel’s celebrated view that a concerto should be “light-hearted and brilliant”; that’s certainly the case here. This dashing and dazzling finale is over almost before you know it. I greatly enjoyed this scintillating performance of the movement, though for the record I should say that the Argerich/Abbado partnership is no less unbuttoned.

Overall, I think this new Cho/Nelsons version has a great deal going for it, but it doesn’t displace in my affections either Argerich or Michelangeli – or, for that matter, Steven Osborne

The Ravel remark that I’ve just quoted wasn’t quite complete. In full, he said: “The music of a concerto should, in my opinion, be light-hearted and brilliant, and not aim at profundity or at dramatic effects”. The Left-hand Concerto stands, arguably, as the direct antithesis to that view and it’s astonishing that Ravel’s two concertos were composed in such close proximity to each other. The Left-hand Concerto was commissioned by the Austrian pianist Paul Wittgenstein. He had lost his right arm during World War I but, with defiant determination, had rebuilt his career as a one-handed artist, commissioning works from a number of eminent composers so that he could construct a new repertoire for himself.

Ravel’s concerto is cast in a single movement but there are three distinct sections and, very helpfully, DG put each section on a separate track; no other recording in my collection does that and whilst it may be a small point, I think DG deserve plaudits. The opening section – by far the longest – begins in sepulchral, mysterious darkness, working towards the piano’s first entry through a continuous but gradual crescendo. Nelsons and the BSO build this crescendo magnificently right up to the dramatic entry of the soloist (tr 4, 2.40). Cho makes a commanding start and when I compared him with Michel Beroff on a 1987 DG recording with Abbado and the LSO it seemed to me that Cho is much better at this grand, rhetorical side of things – and his recording packs more of a punch. This first section mixes darkness and struggle and I wonder whether Ravel was paying his respects to Wittgenstein, recognising what the pianist had had to overcome. Having acknowledged that Cho is very convincing in the big, rhetorical opening I should also say that towards the end of the section there’s a lyrical, musing piano solo and I find him just as convincing there.

The central section is built on jaunty, martial music. This gives Cho many opportunities to display flashes of brilliance. The orchestral side of things is equally exciting and there are also a number of excellent solos from BSO principals – the bassoon and trombone solos are particularly impressive. There follows a return to the grandeur that we experienced at times in the first section, after which the soloist delivers an extended and very challenging cadenza (tr 6, 1:07 – 4:20). Frankly, as I listened to this, I wondered how anyone can play it with just one hand but, of course, Cho is fully equipped to do so and he makes the cadenza a gripping experience for the listener.

As I said, I found a lot to admire in Cho’s account of the G major concerto, though for me the “market leaders” continue to be Argerich and Michelangeli with Steven Osborne not far behind. In the Left-hand Concerto I felt less need to make comparisons; I think Cho is very successful indeed in this work.

The recorded sound is extremely good. The piano sound is rich and firm but also crystal clear. The orchestra is recorded with great presence and the overall sound of soloist and orchestra has great impact. Jed Distler contributes a very useful booklet essay. I think, though, it says a lot about DG’s artist-led approach that the opening paragraph of the essay concentrates on the fact that 2025 is the 10th anniversary of Seong-Jin Cho’s victory in the 2015 Warsaw Chopin Competition and a summary of his career trajectory since then. It’s only in paragraph two that poor old Ravel gets a look-in and we’re reminded that 2025 is his 150th anniversary year.

John Quinn

Previous review: Dominic Hartley (April 2025)

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free