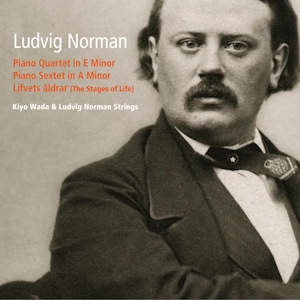

Ludwig Norman (1831-1885)

Piano Quartet in E minor, Op.10

“Lifvets åldrar” suite for piano, Op.51

Piano Sextet in A minor, Op.29

Kiyo Wada (piano)

Henrik Peterson (violin), Sofie Sunnerstam (violin), Nicholas Shardlow (viola), Klas Gagge (cello), Valur Pálsson (double bass)

rec. 2024, Grünewaldsalen, Stockholms Konserthus, Sweden

dB Productions dBCD217 [75]

BBC Radio Three’s “Through the Night” programme draws on recordings shared with and by other members of the European Broadcasting Union, as well as concerts and recordings from further afield. I first came across the music of the nineteenth century Swedish composer, Ludwig Norman, there and I suspect many other British enthusiasts of neglected music will also have done so. That said, only two or three of his works have actually appeared on the programme, most recently the String Quartet in C, Op.42 (his fifth?) – which struck me as being worth a hearing.

Despite having a musical career that included being a concert pianist, teacher and conductor (the one who introduced his friend Franz Berwald’s Fourth Symphony to the world) Norman managed, in a relatively short life, to produce a considerable body of work. His compositions include four symphonies, five other string quartets – the third unfortunately lost – plenty of other works for piano and strings and many pieces for piano. The fine booklet notes to the present CD indicate that “after his studies in Leipzig his starting point for inspiration was German romantic music”- especially Robert Schumann, whose A Major Piano Concerto he introduced to Stockholm, and Felix Mendelssohn. The music of Berwald was also a potential influence and Norman was studying his friend’s chamber music even whilst drafting his own Op.10. He was obviously regarded as an important figure in Swedish musical life, but a brief check indicates current recordings of only two of the symphonies, a small proportion of his chamber music and not much else, so why the neglect? There may be several reasons.

The Piano Quartet, Op.10, is probably a good example of Norman’s early output. As one might expect, the influence of Berwald isn’t far away but the startling originality of that composer’s symphonies and, to a lesser extent, chamber music is not to be found here or elsewhere in the small sample of Norman’s chamber music with which I am now familiar. Nick Barnard’s review of Norman’s Third Symphony similarly indicates that the music was “well crafted and attractive but….resolutely in the second tier”. What we do get here is a pleasant, three movement, Schumannesque work – with the outer movements in E major, a middle movement in C, and no slow movement but a slow introduction, in A minor, to the last movement. The piano writing is closely integrated with the strings and is not overtly virtuosic. Several hearings suggests that the texture within movements is rather unvaried – with few key, tempo or volume changes, standout moments, or particularly memorable melodies.

Although he was obviously a considerable pianist, Norman appears to have had no ambition to compose any virtuoso or experimental solo piano music. His suite “Lifvets åldrar” (The Stages of Life), Op.51 is a collection of six short character pieces – not unlike some of Grieg’s Lyric pieces – that probably reflect Norman’s reportedly “quiet and slow demeanour”. The suite was written around 1878, in the year before Norman was forced to give up opera conducting owing to his poor health.

The best is saved for last. The Sextet for piano, string quartet and double bass, Op.29 is in four movements and is rather more characterful – at least in places. It was composed in 1868-9 in the middle of what must have been the crisis that, in 1870, ended Norman’s marriage to the famed Moravian violinist, Wilma Neruda. No crisis is evident in the music but the first movement (Allegro patetico) has a memorable opening in the strings, echoed in the piano and followed with a lyrical second subject. The playing here is markedly more resolute – and to my mind, successful – than in a rival recording by the Uppsala Soloists with Bengt-Áke Lundin. The note writer points out “delicate arpeggio passages and acrobatic chord passages (that) seem to indicate Norman anticipated the future development of piano techniques for impressionism and modernism”. I certainly wouldn’t go that far but the piano writing is probably more varied and interesting here than in the earlier Piano Quartet. There follows an initially gentle slow(er) movement (Andantino grazioso) with a contrasting middle section.

So far, we have had none of the virtuosity that is to be found in Mendelssohn’s D major Sextet, Op.110, for the same forces, which is an early work despite its posthumous, late Opus number. However, in what is – for me – the stand-out movement, the Scherzo (Allegro molto vivace), we get a very Mendelssohnian scurrying figure in the strings, again echoed by the piano. This winds down to an unexpectedly quiet close. The Finale is marked Allegro con fuoco, although it rarely reflects the marking – at least in this performance. After the Scherzo, which would almost have made a perfectly satisfactory last movement but for its ending, this finale sounds a bit tacked on here and is busy rather than memorable. There are two misleading long pauses – suggestive of endings – but proceedings finally come to a halt after a substantial coda.

The recordings of all the works have an agreeably clear but warm acoustic, the balance is fine and the musicians’ efforts are all good and fluent – if possibly lacking a bit in light and shade.Although these are not premiere recordings, at least of the quartet and sextet, this disc is to be welcomed for airing works of a neglected composer. However,if the necessary enthusiasm is to be sustained to unearth much more of his music, I suspect that performances need a degree more sparkle and urgency than is provided here.

Bob Stevenson