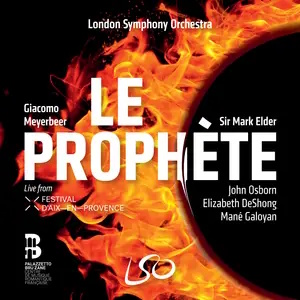

Giacomo Meyerbeer (1791-1864)

Le prophète, grand opera in five acts (1849)

Jean de Leyde – John Osborn (tenor)

Fidès – Elizabeth DeShong (mezzo)

Berthe – Mané Galoyan (soprano)

Le Comte Oberthal – Edwin Crossley-Mercer (bass baritone)

Zacharie, Anabaptist – James Platt (bass)

Mathisen, Anabaptist – Guilhem Worms (bass baritone)

Jonas, Anabaptist – Valerio Contaldo (tenor)

Lyon Opera Chorus, Maîtrise des Bouches-du-Rhône

London Symphony Orchestra, Mediterranean Youth Orchestra/Sir Mark Elder

rec. live, 15 July, 2023, Grand Théâtre de Provence, Arles, France (Festival d’Aix-en-Provence)

Libretto with English translation included

LSO Live LSO0894 SACD [3 discs: 166]

Giacomo Meyerbeer’s Le prophète is a rarity (what impresarios used to dub a “novelty”), and has been thought of as such since the late 1800s. When G.B. Shaw reviewed a revival of the opera in 1890, he joked about critics having to shamefacedly purchase libretti in order to follow the plot. He wrote “I had never seen the opera except on paper.” (Shaw’s Music, II:112) Accomplished musicians such as Saint-Saens believed Le prophète to be of high quality, and the French public seem to have adored the score, or at least respected it, to the point that Reynaldo Hahn wrote “People of my father’s generation would rather have doubted the solar system than the supremacy of Le prophète over all other operas.” (Quoted in Letellier, The Operas of Giacomo Meyerbeer). Singers as diverse as Enrico Caruso, Marilyn Horne, and Placido Domingo lobbied opera houses to perform the opera as vehicles for their talent, so why has the opera largely disappeared from the scene?

Historically, critics tended to blame the score, citing an alleged lack of melody-writing ability on the part of Meyerbeer; even those who enjoyed the opera tended to credit him more as a craftsman than as an artist, a moment-to-moment composer bent on impressing the audience via the ingenuity of his writing. Critics also found fault with the “absurdities” of the plot, or attacked the staging or singing. To be fair to opera companies who have struggled to field a strong vocal team in this music, the piece is not an easy one to cast. The lead role must be sung by a tenor who can both blast and sing sweetly when it is called for, and the contralto who sings the role of the tenor’s mother must be an honest-to-God contralto (or at least a mezzo with some serious low notes). Casting is the least of a producer’s problems when trying to get the opera onstage, however; there is a large chorus, offstage banda, a long ballet sequence typically involving roller skates, massive settings such as a cathedral and castle, and of course special effects such as a populated skating rink and an exploding banquet hall in the final moments of the opera. This combination of demands both musical and technical in nature has led to chaotic performances that don’t place the opera in the best possible light.

To give a single example: an anonymous critic for the New York Tribune was enraged by the Metropolitan Opera’s slapdash production in 1900. “[It] was marred throughout by inconceivably bad stage management and occasionally rendered ridiculous: There was scarcely a moment when the listener could feel that a disaster of some sort was not impending except when Mme. [Ernestine] Schumann-Heink was singing…” He reserved particular scorn for the staging of the Act III comic scena featuring the Anabaptists Zacharie and Jonas, who are supposed to strike a flame to light the lamp that will reveal the true identity of the disguised Count Oberthal: “What was the use of Meyerbeer’s writing a sensational trio, punctuated with the clash of flint and steel, if instead of the tinder bursting into flame as a result of the exertions of one of the sixteenth century Anabaptists, he should illuminate the features of Oberthal with a Swedish safety match at the end? A locofoco two hundred and seventy-five years ago!” (New York Tribune, January 11, 1900) Although there have been successful productions of the opera in the United States and Europe in the years since that fateful match strike, the opera has not caught on.

Luckily for listeners interested in a (kind-of) complete Le prophète, Mark Elder and his merry band of Meyerbeerians do their best to sell the opera in this live performance from the Festival Aix-en-Provence, and for the most part, they succeed. The chorus, prepared by Benedict Kearns, is beautifully balanced throughout the opera, and they follow the score’s many details to the letter. The stirring “Aux armes!” choral section from the first act features an inserted high C from the women of the chorus, who hold nothing back. Powerful orchestral interjections are emphasized by the tight ensemble Elder draws from the players. There are many characterful contributions from individual players in Meyerbeer’s many orchestral solos. At the very outset of the opera, the dialogue between the pit and offstage clarinets of the Act 1 prelude is sensitively shaped, one presumes by guest principal James Burke and clarinetist Chris Richards. The long (some might say distended) ballet sequence in Act III is given a solid performance by the orchestra, but it never gets the pulse racing. The cumulative effect of the various dances ending with final Galop should make the listener rocket out of his chair with enthusiasm, but Elder keeps his forces under tight control, giving the performance a feeling of neatness rather than galvanizing energy. Although this recording may not be the last word in crackling excitement, Elder’s attention to detail is commendable; listen to the shaping of the introduction to Fidès’s aria “Donnez pour une pauvre âme.” The strings and low winds are all on the same page with their phrasing, the winds matching the bowing of the strings, and all carry out the small, sighing crescendi and decrescendi in perfect unison.

The soloists are uniformly strong. In the punishing role of Jean, John Osborn sings with assurance and panache. Although his timbre is attractive and he never sounds overmatched, he is not a heroic tenor along the lines of a César Vezzani, Antonio Paoli, Alberto Alvarez, or more recently, James McCracken or Guy Chauvet. Is this a problem? Osborn, who is much more of a bel cantist than the previously-mentioned crowd, summons plenty of sound for the big moments, neatly carries out Meyerbeer’s occasionally stratospheric registral demands, and his lighter voice can more naturally color the visionary passages that sound bizarre in McCracken’s performance when he switches from chest to head voice. “Roi du ciel” has an interesting swagger to it, very different from the more effortful versions offered by heavier voices.

Elizabeth DeShong’s Fidès is marvelous. Her low B-naturals in the previously-mentioned “Donnez pour une pauvre âme” aria in Act IV sound like a natural part of the phrase, rather than a problematic chore, and she handles the optional coloratura with ease. The resigned melancholy that permeates the role never dissolves into self-pity. Mané Galoyan absolutely nails the role of Berthe, giving the first completely satisfying portrayal of the role on a commercial recording. (Renata Scotto’s assumption of the role from the 1970s is exciting, but the voice is already sounding frayed, and the music doesn’t suit her voice.) From a dramatic standpoint, Galoyan convincingly encompasses both the bucolic music of the opening act, and the increasingly hysterical music of the latter part of the opera. Her death scene, sung to the accompaniment of a beautifully-played cello solo, is touching and very well sung. This scene is a wonderful example of Meyerbeer’s acute stage instincts; it’s a mystery why it is missing from the old edition of the score, but I’m glad that this production incorporated it.

When seen in performance, there is a danger of the three Anabaptists giving off a Three Stooges vibe and becoming figures of fun (watch the 2017 production from Toulouse for a taste of this – the trio starts out very well, but lose their threatening nature very quickly). Based on the audio evidence, the Aix-en-Provence performers managed to avoid becoming stand-ins for Larry, Moe, and Curly, letting loose with torrents of sinister tones.

Mark Elder uses the 2011 critical edition of the score based on Meyerbeer’s autograph manuscript. The score offers alternate arias for Jean and Berthe, as well as an intriguing soft introduction for two clarinets in the famous Coronation March that makes the massive buildup more thrilling. I wish they had used Berthe’s “standard” Act 1 aria, “Mon coeur s’élance et palpite,” which is frankly more of a showpiece than the “Voici l’heure ou sans alarmes” aria, which is pretty but forgettable. (Hat tip to the lovely cello soli, however!) There are numerous nips and tucks to the score, presumably to save time, but some of the cuts are inexplicable. The “bouffe” trio mentioned above, for example, is missing, and many of the small cuts do nothing to strengthen the passages from which they are removed. To be fair to Maestro Elder, he is following a long and illustrious tradition in peppering this opera with cuts. I own a copy of the vocal/piano score that once belonged to the Chicago Civic Opera, which performed the opera in the 1924 season with now-forgotten American tenor Charles Marshall as Jean, Louise Homer as his long-suffering mother, and Alexander Kipnis as Zacharie. The conductor, Roberto Moranzoni, slashed the opera to pieces. The “bouffe” trio is missing here too, as is Berthe’s opening aria; huge cuts disfigure Jean’s aria “Roi du ciel,” and the difficult passage in thirds in the Jean/Fides Act IV duet is dropped. Almost all of the choral contributions in the final scene are gone, the denizens of the banquet hall dispatched with celerity.

For the connoisseurs (aka opera nerds) interested in such things; there are many other small differences between the modern and old editions. In Jean’s Act III prayer, “Dieu puissant,” the brief cadenza (“à ton peuple égaré…”) possesses no markings of any kind in the new critical edition. In the Chicago score, a “Nouvelle Edition” similar to Brandus edition from 1865, several crescendos are indicated for this cadenza, with a subito piano, marked “très doux” on the high A natural. At the end of the prayer, the second cadenza (“la grâce va s’étendre sur vous” is marked more closely in both scores, but another high A natural is again marked “très doux” in the old score, and the held note that gets the singer out of the cadenza contains a messa di voce, or an old-school crescendo/decrescendo effect once beloved of bel canto singers. French vocal/piano scores of the 1800s seem to have many small indications that do not appear in the full scores; I’ve never seen any research on the topic, but my understanding is that the vocal scores were marked by someone who noted requests of the composer or conductor at the premieres, and then added these to the eventually published scores. (The vocal/piano score for Massenet’s Manon is absolutely littered with small instructions to the singers in terms of articulations and dynamics that do not appear in the full score, for example.)

For those who wish to hear competing versions of the opera, the competition is scarce. The only other recording of the 2011 critical edition is a 2017 CD set conducted by Giuliano Carella. My colleague Mike Parr (review here) prefers the Carella recording to the Elder/LSO, mostly on the basis of the fresher vocal estate of Osborn, the conducting of Carella, and the more natural acoustics. I agree with Mr. Parr’s assessment re Osborn, but I find the other casting on the 2017 recording to be a major deficit. The 2017 Berthe, Lynette Tapia, is a representative of what was once a common soprano “type,” with a bright, schoolgirlish tone that becomes piercing in the upper register. The Fidès is also weak, as noted by Mr. Parr, and I find the Anabaptist trio too lightweight for their roles. The 1977 commercial recording featuring a contrastingly heavyweight Met cast offers more meaty singing, but the performance suffers from Henry Lewis’s generalized conducting, and some listeners will find James McCracken’s famous use of head voice to be disconcerting. (At the time, some claimed it was otherworldly, but to my ears it sounds like a hooty, aging mezzo, not at all in line with the heroic, stirring sounds that otherwise emanate from his mouth.) Much better is a 1979 Met live recording likely taped on a handheld recorder featuring a cannon-voiced Guy Chauvet and the fearless Rita Shane as Jean and Berthe, with an exceptionally energetic Charles Mackerras in the pit. This is the best recording of the ballet music; Mackerras kicks the music into high gear in the final Galop, giving the brass permission to go for the gusto, and the audience goes wild, as it should. You also get the benefit of Marilyn Horne’s magical Fidès. Individual arias from the opera were recorded during the 78rpm era; the best of these is a “Roi du ciel” by a viscerally exciting Cesar Vezzani, whose masculine and focused tone makes one desperately wish for a complete recording.

Richard Masters

Previous reviews: Michael Cookson (September 2024) ~ Mike Parr (August 2024)

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free