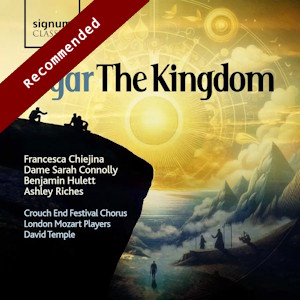

Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934)

The Kingdom, Op 51 (1906)

Francesca Chiejina (soprano – The Blessed Virgin); Dame Sarah Connolly (contralto – Mary Magdalene); Benjamin Hulett (tenor – St John); Ashley Riches (bass – St Peter)

Crouch End Festival Chorus

London Mozart Players / David Temple

rec. 2024, Alexandra Palace Theatre, London

Text included

Signum Classics SIGCD896 [2 CDs: 89]

The Crouch End Festival Chorus was founded in 1984 by David Temple and John Gregson; Temple has been its Music Director right from the start. I’ve experienced their work on several previous occasions, both live and especially on disc, most notably in two recordings of music by Parry: Prometheus Unbound (review) and, to an even more impressive degree, Judith (review). So, I’m well aware that this is a most accomplished choir. I was delighted, therefore, to receive for review this recording, which was made to celebrate the choir’s 40th anniversary. To mark such a milestone, they could have chosen to record one of the great staples of the choral/orchestral repertoire, such as Elijah, Creation or perhaps Elgar’s most popular work in the genre, The Dream of Gerontius. Hats off to David Temple and his choir for choosing an Elgar work which, though not neglected, is neither performed nor recorded with anything like the frequency of Gerontius. By a neat piece of symmetry, the first commercial recording of The Kingdom was made in 1968 to celebrate another anniversary; Sir Adrian Boult elected to record the oratorio to mark his 80th birthday. This new recording conducted by David Temple is, I believe, the work’s fifth recording; the Boult version was followed by performances conducted by Leonard Slatkin (in 1987 for RCA 7862-2-RC), by Richard Hickox (in 1989 for Chandos CHAN 8788/9) and, most recently, by Sir Mark Elder (review). Actually, Elder’s fine recording, which is the only one not made under studio conditions, isn’t all that recent; it was made in 2009.

It was through that Boult recording, which I first encountered in the early 1970s, that I came to know and love The Kingdom. I have never forgotten a statement that Sir Adrian made in the booklet which accompanied his recording: “I think there is a great deal in The Kingdom that is more than a match for Gerontius, and I feel that it is a much more balanced work and throughout maintains a stream of glorious music whereas Gerontius has its up and downs. Perhaps I was prejudiced by hearing a great friend of Elgar’s [Frank Schuster] (who was very kind to me in my young days) jump down the throat of a young man who made this criticism [that Gerontius was a finer achievement than Kingdom]: ‘My dear boy, beside The Kingdom, Gerontius is the work of a raw amateur’.” I think Schuster’s judgement went way too far but, having said that, I know what he meant. There are several reasons why one could argue that The Kingdom (1906) represents a significant advance on Gerontius (1900). For one thing, in Gerontius, Elgar set someone else’s words, albeit he drastically pruned Newman’s poem in order to fashion it into a workable libretto; in both The Kingdom and its predecessor oratorio, The Apostles, Elgar very successfully created his own text, drawing, to excellent effect, on a wide variety of Scriptural sources. Another factor is the choral writing. I’ve had the good fortune to sing in multiple performances of all three oratorios over the last four decades and I feel that Elgar’s writing for the chorus became better over the years, reaching a pinnacle in The Kingdom. Finally, there’s the question of the orchestration. Much of the scoring in Gerontius is superb, but by the time he came to write the successor oratorios, Elgar was at the height of his powers as an orchestral composer: the dazzling, virtuoso scoring of In the South (1904) came just after the composition of The Apostles (1903) and the great achievement of the First Symphony (1908) lay only a couple of years into the future after The Kingdom. One can make a case that the orchestration of The Apostles is in places even more inventive than what he achieved in The Kingdom, but it’s a close-run thing; as an example, the writing for the horns in The Kingdom often has a Straussian opulence and importance. As I said, I think Frank Schuster’s statement was far too sweeping but I do agree with Sir Adrian when he talks about the evenness of The Kingdom. None of this is to diminish Gerontius; it’s a masterpiece; but there are, I believe, many reasons to accord the other two oratorios at least as much esteem.

Common to all three of Elgar’s oratorios is his use of leitmotifs in the manner of Wagner. The device is very evident in Gerontius but it’s even more prominent in The Apostles and in The Kingdom. The score of the latter oratorio is peppered with thematic cross references to The Apostles; that’s no surprise, because the two works are inextricably linked. Indeed, in his absorbing booklet essay Jeremy Dibble quite rightly devotes a lot of space to The Apostles. That said, either of these oratorios can perfectly satisfy the listener when heard as a standalone work.

Since this recording celebrates the anniversary of the Crouch End Festival Chorus, it’s right and proper to consider their contribution first. I was very impressed. They’ve been balanced very successfully in relation to the orchestra and as a result their singing can be very clearly heard. Rightly, the chorus members are listed in the booklet; I haven’t counted the number of names precisely but I guess about 120 singers are involved. There’s a consistent firmness to their tone and the choir deserves special plaudits for the clarity of their diction. The soprano line has an attractive freshness to it – top notes are truly hit – while the basses provide a good, solid foundation. Following in my vocal score, it was evident that the choir is very disciplined and pays excellent attention to detail. There were a few instances where I thought their quiet singing was not sufficiently hushed. However, eventually I drew the conclusion that on those occasions they must have been told to mark up the dynamics a bit because elsewhere the dynamics, both loud and soft, were very well observed – on more than one occasion, I noted a definite difference between pp and ppp. I hope the other members of the CEFC will not take it amiss if, as a fellow member of the Tenors’ Union, I single out the Crouch End tenors for recognition. As is almost invariably the case in choirs nowadays, the tenor section is numerically the smallest – twenty-one singers are listed – but without ever over-singing these tenors make a splendid contribution. But, in truth, the whole choir gives a consistently fine performance throughout the work, worthily marking their 40th anniversary.

The four soloists acquit themselves very well. Dame Sarah Connolly is a notable presence in the role of Mary Magdalene. Many of her principal solo contributions take the form of passages of narration. In each of these she tells the story in a compelling fashion. The best example of all comes in the passage, just before the great soprano aria ‘The sun goeth down’, where she tells of the arrest of Peter and John; here, her narration is particularly gripping. Elgar gave his mezzo soloist one other important passage: the duet with the soprano soloist which forms the whole of the short Part II of the oratorio, ’At the Beautiful Gate’. This is exquisite, poised music, and in this performance the two solo voices are very well matched: Dame Sarah and Francesca Chiejina have rich timbres but that richness in no way compromises the clarity of their diction. I was highly impressed by Benjamin Hulett as St John. This is a role in which it can be hard to make an impression. To date, the exemplar has been Alexander Young on the Boult recording who emphasised the lyrical side of the role, singing with elegance. I’m afraid John Hudson on the Mark Elder recording is no match for Young, but Hulett most certainly is. In fact, I think Hulett even surpasses Young. The tenor’s biggest moment comes in Part IV with the solo ‘Unto you that fear His Name’ Young delivers this very well and with exemplary attention to dynamics. Hulett is even better, though. He offers open-throated, lyrical singing, both in this solo and elsewhere. I don’t know what age Young was when he made the recording but Hulett consistently impresses with youthful-sounding ardour and for the way he characterises his role. I would now rate him as the finest exponent of this role on disc.

For me, there are three touchstone moments in any performance of The Kingdom. One of these is the great soprano scena ‘The sun goeth down’ which concludes Part IV. This is a formidable challenge to the singer because Elgar requires still, rapt singing at the beginning and end but ecstatic rapture in the central passage. I don’t think I’ve previously encountered the Nigerian-American soprano Francesca Chiejina. I think she gives a very convincing account of the extended central section of the aria, rising successfully to its dramatic challenges, though in places the music is pressed forward a bit too urgently, I feel; that may be the conductor’s decision of course. I’m less convinced, however, by her delivery of the opening and closing pages; I’m afraid she doesn’t sing these parts of the aria quite softly enough; some atmosphere is lost. At this point I should say that Ruth Rogers, the leader of the London Mozart Players, plays the lovely violin solos with great poetry. Elsewhere in the oratorio Ms Chiejina sings very well indeed. On the Elder recording the soprano soloist is Claire Rutter, who makes a fine overall contribution. She does very well in ‘The sun goeth down’, for example making a bit more of the words at the outset than Ms Chiejina does. I also feel she’s more attentive to the dynamics. Her urgency in the central section is impressive while the poetic outer sections, where she combines beautifully with the Hallé’s leader, Lyn Fletcher, are touching. Ms Rutter’s performance of this aria is a fine achievement, all the more so since this is a live performance. All that said, Margaret Price’s rendition of ‘The sun goeth down’ on the Boult set remains peerless. The soprano’s opening phrases are marked molto espressivo and we get that more from Ms Price than from any other soprano I’ve heard; with her, the rapt ending of the aria is sheer poetry. In between, Price communicates the full range of emotions that Elgar wrote into this aria: at ‘The Gospel of the Kingdom’ her singing of this exultant passage is absolutely compelling. Her account of the aria is an outstanding piece of singing which crowns her memorable contribution to Boult’s recording. It’s worth saying, too, that on the Slatkin recording Yvonne Kenny gives a fine rendition of ‘The sun goeth down’, though I’m not wholly convinced by the way Slatkin conducts this episode.

My second touchstone moment is the extended solo for St Peter in Part III, beginning at ‘I have prayed for thee’. Boult’s soloist is John Shirley-Quirk and he is wonderfully eloquent in this passage as, indeed, he is throughout the oratorio. There’s complete conviction in every note and every word that Shirley-Quirk sings. He stamps his authority on this aria from the outset and gives an unforgettable performance. It’s been a little while since I listened to the Elder performance. There, St Peter is sung by Iain Paterson and I must admit I had forgotten just how good he is. He has a large voice – he is a noted Wagner singer and, for example, took the role of The Wanderer to excellent effect in Elder’s 2018 recording of Siegfried (review). He’s a consistently excellent St Peter and gives a commanding account of the solo in question. Furthermore, though his voice may be a large one, Paterson demonstrates lots of subtlety, both here and elsewhere in the work. Overall, his assumption of the role in general and his delivery of this lengthy solo in particular, is splendid. Ashley Riches more than holds his own against the formidable competition provided by his two rivals. Throughout the oratorio, I admired the care and imagination with which he invests the words. His voice is firm and evenly produced – the many top Fs in the part are effortlessly produced. I felt drawn in by his singing and the way he communicates. In this big solo he is completely convincing in his portrayal of Peter as a leader. I’ve heard Riches sing on a number of occasions, both live and on disc, and though I’ve always admired his performances I think this the best I’ve heard from him.

My third touchstone passage in The Kingdom is the ensemble ending of Part III, beginning at the point where Peter sings ‘Repent, and be baptised…’ These pages contain music that shows Elgar at his greatest and the music never fails to move me, whether I’m singing it or listening to it. This new performance is absolutely splendid; you feel that all the musicians are totally committed (not that there’s any lack of commitment elsewhere, I hasten to add). Elgar’s music really takes wing at ‘The First Fruits of his creatures’ (Cue 118 in the vocal score), at which point David Temple and his forces respond terrifically. The whole of this episode (from ‘Repent’) is brought off marvellously; in fact, I’d go so far as to say that the performance is touched by greatness in these pages.

I’ve concentrated, perhaps inevitably, on the singers but I should say something about the orchestral playing. The London Mozart Players make an excellent contribution and I was especially pleased by the finesse with which the more delicate passages – of which there are many – are delivered. The LMP string section is a bit smaller (10/8/6/7/3) than those of the full-sized symphony orchestras on the other recordings but I didn’t find this a drawback. One reason I’ve not included the Hickox recording in any comparisons is that the Chandos engineering, usually so impressive, is on this occasion somewhat misjudged and there are places where either the engineers or the conductor – or both – allow the London Symphony Orchestra to be too dominant; this doesn’t happen on this new recording. There is one slight oddity on the Signum recording: the bass drum is given greater prominence than on any other recording, but I quite enjoyed the opportunity to notice Elgar’s telling use of the instrument. The LMP take a very full part in the success of this performance and in the big moments there’s no lack of tonal weight.

David Temple has clearly prepared this performance assiduously. He has contributed a personal note about The Kingdom to the booklet. I didn’t read this until I’d finished all my listening and when I did, I was fascinated by one point he made. He comments that the only evidence we have of Elgar’s approach to the work is his 1933 recording of the Prelude with the BBC Symphony Orchestra. Temple notes that Elgar’s performance is “full of colour, energy and pathos…totally fluid and of the moment”. Fortunately, I have that performance; it’s in Vol 3 of EMI’s utterly indispensable ‘The Elgar Edition’ and, naturally I played it as soon as I’d read those comments. Temple is absolutely right; there’s palpable urgency in Elgar’s reading – and poetry too. Elgar’s performance takes 8:40; Temple’s interpretation – which is by no means a slavish imitation – plays for 8:33. The reason I mention this is that David Temple says he found Elgar’s recording “totally liberating and it has strongly influenced my interpretation of the whole score”. I think that’s a most interesting point and it seems to me to be a fair starting point for any consideration of the whole score, not least because all the principal themes are unveiled during the course of the Prelude. I found Temple’s conducting of the score thoroughly convincing. He brings out both the drama and the poetry in the work. There were one or two occasions where I felt that he pressed the tempo just a bit too much – in parts of the central section of ‘The sun goeth down’, for instance – but overall, I admired his pacing of the music, his attention to detail and the way he conveys the overall sweep of this great score.

The recording, which was made under studio conditions, has been produced by Tim Oldham and engineered by a team led by Mike Hatch. They’ve done an excellent job. The sound is very well balanced and detailed, has an excellent dynamic range, and has plenty of impact. The documentation accompanying the release is very good indeed.

As I said at the start, there have now been five recordings of The Kingdom. I’m not sure that the Slatkin performance is currently available. He has a good solo team, though the tenor is a bit ordinary, and the chorus and orchestra do well. However, there are too many occasions where I feel that Slatkin misjudges the tempo and the recorded sound is very studio-bound. The Hickox version has the LSO and London Symphony Chorus on excellent form but I find the soloists less persuasive than on some other recordings and I feel the engineering is a bit overcooked. For me, both of those recordings rank behind the other three. Boult’s version is wise and evidences deep Elgar experience but, though it’s the version with which I grew up, I now feel there are times when Sir Adrian is a bit too measured; I’d welcome more electricity in places. On the other hand, as I’ve indicated, Boult has two of the finest soloists on disc The Mark Elder version is excellent and still my favourite, even though his tenor is less convincing than the other soloists; for me, Elder paces the score in an ideal fashion and there’s a sense of occasion, which one gets from a live performance. How does this new Signum version stack up against such competition? Very well, I’d say. The soloists are very good indeed and David Temple conducts with great empathy and conviction. Fittingly, the Crouch End Festival Chorus celebrate their 40th anniversary with choral singing which is as good as any on disc. Overall, this is a recording that is worthy to rank alongside the Boult and Elder versions.

This recording is a fine achievement which amply demonstrates the greatness of Elgar’s score.

John Quinn

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free