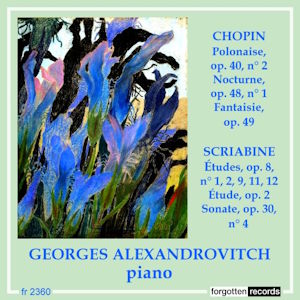

Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849)

Polonaise in C minor, Op 40/2

Nocturne in C minor, Op 48/1

Fantaisie in F minor, Op 49

Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915)

Six Études: Op 2/1, Op 8 Nos. 1,2,9,11,12

Piano Sonata No. 4, Op 30

Georges Alexandrovitch (piano)

rec. 1958, Paris

Forgotten Records FR2360 [42]

Biographical material on Ukrainian-born pianist Georges Alexandrovitch is hard to come by. I am grateful to the lovely people at Forgotten Records for what I have. Born in Kiev in 1926 his family seemed to have moved to Odessa early on. In those early Soviet days, there was a set educational path for students deemed to have considerable musical talent and Alexandrovitch was pushed onto it very early on, enrolling at the prestigious Stolyarsky school in the city (very successful at producing top quality fiddle players by the way). He was given some opportunities to shine as a prodigy with concerts in Moscow and Leningrad and at some point, transferred to the Conservatory in Odessa. Gilels, a native of Odessa had been 14 when he had made the jump up and Alexandrovitch had the same teacher, Berta Reingbald.

Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 must have turned his world upside down. Historically speaking, it is likely that his family’s lives were also monumentally affected by the terrible famine (the Holodomor)that ravaged Ukraine in 1932/33. I cannot find any details about this, but maybe that was the reason for their moving to Odessa in the first place. Anyway, it seems that in 1941 he had gone to Moscow to enrol at the Conservatory (run by the great Alexander Goldenweiser) only to be forced back to Odessa. That Southern port city was under siege until October and thereafter under the Nazi yoke until liberation in April 1944. I cannot trace Alexandrovitch’s circumstances in these years, but I know that in 1945 he went to Romania and enrolled at the Bucharest Conservatory. He was spotted by George Enescu who helped him in 1947, secure funding from the French government to study in Paris. At the age of 21, I wonder how he must have played. On his records we hear the unmistakable blend of Russian and French traditions, but what was the sound that caught Enescu’s ear in those earlier days?

In Paris, Georges Alexandrovitch studied with Marcel Ciampi and Lazare-Lévy, who had also taught Solomon many years before (Solomon’s Chopin by the way, is hugely underrated and must have been heavily influenced by his teacher). In 1950 he attracted interest when he won one of the top prizes at Concours de Genève, then, as now, a big-time competition. He undertook further studies with Marguerite Long (many did) and won a prize (I am unsure what category) at the competition bearing her name around this time as well. His apprenticeship years complete, he was ready to embark on the life of the successful concert virtuoso.

From 1953 he seems to have started to give regular recitals and appear in concerti. It is very hard to find details online, but I believe he played Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto at the Salle Pleyel in March of that year with the Orchestre Lamoureux and gave a debut recital at the Salle Gaveau in November. He toured often in France and was also heard in Switzerland, Belgium and Italy. I managed to confirm a Wigmore Hall date on 7th February 1958, but I don’t know the programme.

For us record collectors the saddest part of the story is the paltry legacy he left to us on vinyl. As far as I can tell he only made two gramophone discs. The first, we hear on this CD, was made for the obscure French label Président in 1958. The second was for a label called Musidisc. Forgotten Records have sourced a clean copy of the 1958 LP which contains a side each devoted to Chopin and Scriabin. The CD documentation doesn’t say so, but the sound is mono.

The music by Chopin is a polonaise, a nocturne and the fine Fantaisie in F minor. For the first two pieces, Alexandrovitch will inevitably be compared with Arthur Rubinstein, who recorded them pre-war for HMV with repeat performances thereafter. Rubinstein called this polonaise in C minor a symbol of Polish tragedy. Alexandrovitch gives a grand reading, rich in drama and scale. The left-hand chords are weighty, but he lets the sun in beautifully in the trio section (from 2:52) showing real gentleness-second time round too. It is a great reading of this miniature masterpiece. Rubinstein re-recorded it after the war for Victor in 1950 and took the first section repeat which he didn’t for HMV. Alexandrovitch omits it too and that is a shame. In the nocturne of the same key, Chopin writes in a similar style; forlorn outer sections enclose a more hopeful serene central section. The work is on a smaller, more intimate scale of course but Chopin does write a great rising chorale in the middle section which is given its full measure here (impressive double octaves). Alexandrovitch is songful and heartfelt and again sets down a jewel of a performance. Rubinstein’s nocturnes, indeed, all his pre-war Chopin is due a re-appraisal (could Pristine be tempted?) as the EMI remasterings are getting on a bit now.

The Fantaisie is one of Chopin’s finest works. Writing in a free form, unrestricted as it were by convention he created a masterpiece for the age – and what an age the 1840s was. Alexandrovitch adapts to the style-shifts brilliantly. Virtuosic arpeggios combined with a sense of theatre and showmanship make it thrilling, but what pathos to his touch in those yearning sighs. His fingering is exquisite in the fast figurations he is tasked with, yet listen to how he stops the clocks at the lento sostenuto; it takes your breath away. Overall, there is a touch of class in this reading. It is not episodic or quixotic, nothing is done for effect or feels mannered. I was reminded a little of Claudio Arrau who also played this piece marvellously well in a similar style. In the 78rpm era the version to have was Alfred Cortot on HMV DB 2031/32 (3 sides). It is a temperamental reading and as with much Cortot did, one grows into it over time. Marguerite Long also recorded it for French Columbia on 4 ten-inch sides but with the greatest respect to her, that version was never competitive and listening to it after hearing her pupil play it so well is not recommended.

Alexandrovitch’s Scriabin is every bit as impressive as his Chopin. Interestingly he chooses a group of six études, all written in the minor key for starters. The mini-program of early Scriabin is highly effective and intelligently structured with the great G-sharp minor work Op. 8/9 as the central peak. This work is hard to play well both technically and interpretively. Alexandrovitch manages the difficulties with nimble skill and characteristic finesse. He brings out the inner voices in this work magically. He is just as effective in the following moody B-flat minor work that follows it, although the sustained chords do highlight that he is playing an instrument that has – shall we say? – seen better days. The études conclude with the famous octave study that is the D-sharp minor. Alexandrovitch captures the tumultuous eruptive nature of the work really effectively. If you don’t know the études you really should get to know them. If you like Chopin and Rachmaninov, you will adore them. There are many great versions to choose in the catalogue. When you are suitably prepared, sit back and listen to these six choice cuts, played in the grand tradition I believe Scriabin himself would have recognised.

The disc concludes with the short Piano Sonata No. 4 of 1903. Less than seven minutes in duration, this piece was written at the end of Scriabin’s early period, opening the door to the new harmonies and techniques he would subsequently adopt. Reams have been written about the mystical nature of his music from this date forth, a good deal of it by Scriabin himself; without wishing to be dismissive, this analysis interests me very little. There is a poem to go along with the sonata if you are so inclined – and I usually pass on this, too. The music speaks to me directly. It is idyllic, blissful, dreamlike in the first movement and charmingly merry in the second. There is nothing I hear to darken the mood, yet the language has clearly moved on from the études, into the post-Romantic impressionistic idiom being explored in literature for the piano around Europe, most famously in France.

Alexandrovitch gives a reading of the sonata that is, in one word, “French”. In his accents and rubato, I hear that sense of panache and swagger one associates with the Paris school and his subtlety of touch in the first movement is pure class. I wonder how many great Ravel and Debussy players performed this work in the 1950s – or now, even. It breathes the same air and here gets a stunningly impressive performance.

My biography of Georges Alexandrovitch tells me he also composed. Much of his output is unpublished but a few works were taken on by Éditions Durand and are still available today. The last reference I can find of him in concert was in Monte Carlo, playing Liszt’s Piano Concerto No. 2 in 1978. I could find no further information after that date. The twenty year period from his Président record to this last date is frustratingly blurry.

Alexandrovitch’s second record in 1962 was of music by Polish composers: Chopin, Lessel and Szymanowska (no relation to the much later Szymanowski). Perhaps Forgotten Records will remaster it one day – or maybe they will dig up another forgotten record for us to hear and celebrate once again, as here with the unheralded Georges Alexandrovitch. Their website is a treasure-trove if you are interested in the nooks and crannies of the old catalogues. As you can tell, I was bowled over by the label’s work on this release and recommend this CD to all lovers of great piano playing.

Philip Harrison

| Availability |  |