Maurice Ravel (1875-1937)

Concerto for piano and orchestra in G Major M83 (1931)

Concerto for the left hand for piano and orchestra in D Major M82 (1930)

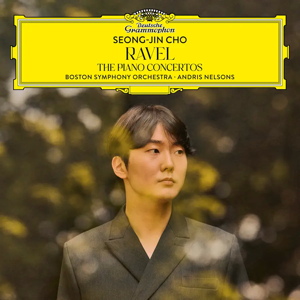

Seong-Jin Cho (piano)

Boston Symphony Orchestra/Andris Nelsons

rec 2023/24, Symphony Hall, Boston, USA

Reviewed as a download

Deutsche Grammophon 4866820 [41]

The Lithuanian-born French pianist Vlado Perlemuter studied with Ravel for a six month period at Ravel’s house in Montfort-l’Amaury in 1927. It’s fascinating to read, via one of his pupils, Perlemuter’s summary of what was important to Ravel: ‘He was demanding, even intransigent, on the question of tempo, the subtle relationship between freedom and rigour, the clarity of the discourse, and above all the unique character of each of his compositions, setting himself apart from classical and romantic art.’

These comments were in my mind when listening to this new release from DG. Let me say at once that these are on the whole well played performances of both concertos. Seong-Jin Cho is an awesome talent. Andris Nelsons and the Boston Symphony Orchestra provide a luxurious accompaniment, honed in live performances in Boston before the recording was made. The sound is superb, with a wide dynamic range (although you will need excellent headphones or speakers to fully catch the wonderfully hushed opening of the Left Hand concerto). Those who already have Seong-Jin Cho’s recent release of Ravel’s solo piano music (DG 4866814) will understandably be interested in this.

And yet, I couldn’t help feeling that what’s presented on the disc epitomises an unspoken but accepted aesthetic around modern performances of Ravel: a soundworld which is precise, brittle, quietly lyrical, colourful, yes, when required, but above all, controlled. Seong-Jin Cho’s playing seems to be principally concerned with conveying an emotional reticence, lucid but enigmatic, in what feels like a sandboxed environment created by him and the orchestra. Worse, the overly precise lyricism that Cho seems to be striving for degrades into listlessness at times. I really struggled with the enervated feel every time the music slowed in the Concerto for the Left Hand for example and his performance of the G major Concerto’s Adagio can’t seem to rid itself of an inherent lethargy. I longed for greater momentum, a sharper contour to the sound and some spontaneity, at the very least an occasional in the moment deviation by pianist and conductor from the predetermined tonal template. As it stands, I think it’s the balance in that ‘subtle relationship’ that Perlemuter talks about which gets lost here, where what is perceived as rigour dominates the interpretation.

It doesn’t have to be like this. The most recent performance of the G major concerto I had heard before the DG is another new 2025 release, where Jean-François Heisser directs the Orchestre de Chambre Nouvelle-Aquitaine from the keyboard (Mirare MIR582). Without being in any way a gimmick this unusual arrangement feels liberating because it literally puts the pianist in charge. Here that is important. Heisser was a pupil of Perlemuter (and reported the reflections quoted above). He does, I think, show us a different approach to the G major concerto where there is greater freedom of expression and a degree of risk taking without being overly impetuous. This is apparent not just in his attractively edgy playing and much more colourful sound, but in the nimbleness of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine orchestra compared to Boston, as well as their obvious sheer enjoyment of the score. Comparing the ending of the first movement of the G major here to the DG recording for example, I find an unfeigned and welcome raucousness in Heisser’s players which is lacking in the much more constrained sounding BSO. Overall, I found this account deeply satisfying, a subtle and welcome corrective to current performance practice in Ravel as epitomised on the DG recording.

One other modern tendency is an unquestioned assumption by a lot of record companies that the Ravel concertos are generally best heard in the company of each other. There is obviously a point about having ‘library’ versions with a consistency of view that a single performer might enable, particularly with the 150th anniversary of Ravel’s birth in mind. Seong-Jin Cho and DG have clearly conceived their Ravel project in this way. But what if you just want to put on a record and see where that takes you? Hearing either concerto with something different can be a revelatory experience. Try Prokofiev for example, on the famous DG Argerich/Abbado recording (DG 4474382) which places the G major alongside Prokofiev’s Third, a joy. Another rewarding pairing is Andrei Gavrilov playing the Left Hand Concerto with Prokofiev’s First with Simon Rattle and the LSO (Warner 2564611661). Other composers are available, and I won’t labour my point, but I’ve enjoyed so much hearing these juxtapositions again. Listening in this way also challenges us to avoid preconceptions about Ravel. As Jean Echenoz, author of a superb novel about the composer, writes: ‘An Ascetic and a dandy, casual and rigorous, tragic and mocking, Maurice Ravel is a paradoxical hero. The more you try to get to know him, the more he eludes you, gracefully taking leave without hanging around.’ Quite.

Dominic Hartley

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.