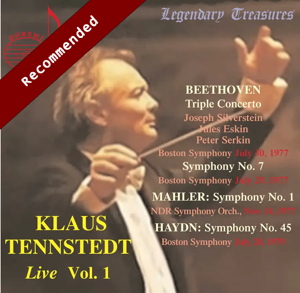

Klaus Tennstedt (conductor)

Live Volume 1

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Symphony No. 1 in D Major (1888)

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Symphony No. 7 in A Major, Op.92 (1812)

Concerto for Violin, Cello and Piano in C Major, Op.56 (1805)

Joseph Haydn (1732 – 1809)

Symphony No. 45 in F sharp Minor, ‘Farewell’, Hob. I/45

Joseph Silverstein (violin), Jules Eskin (cello), Peter Serkin (piano)

Boston Symphony Orchestra

NDR Symphony Orchestra (Mahler)

rec. live, Tanglewood, 20 July 1979 (Haydn), 29 July 1977 (Beethoven 7), 30 July 1977 (concerto); Hamburg, 14 November 1977 (Mahler)

Doremi DHR8241/2 [2 CDs: 156]

As the short, single page of liner notes makes clear with this release, Klaus Tennstedt’s career was brief, but glorious. After exploding onto the international music scene in the late 1970s, he blazed across the world like a comet lighting the sky, until burning out a little over a dozen years later, racked by self-doubt and ill-health, dying of throat cancer in January 1998, just four years after his final concert. In spite of the comparative brevity of his international career, we are fortunate that he made a number of studio recordings, virtually all for EMI (now Warner Classics) and mainly with the London Philharmonic Orchestra whom he led with distinction between 1983 and 1987, even if most agree that he was at his best in the concert hall. In recognition of the latter point, Doremi have issued six double-CD sets documenting live concerts he made in both North America and Germany, the current release under review being ‘Volume 1’. Although the publicity blurbs accompanying these issues proudly proclaim they are ‘first releases’, most seasoned collectors will know that all the works presented here have been around on unofficial labels for years, but it is good that they are now receiving a ‘mainstream release’, especially in light of one of the items on this particular album.

What is often overlooked when considering Klaus Tennstedt’s career is his highly productive and close working relationships with virtually all the major North American orchestras, and in this release there are three performances given with the Boston Symphony with whom he made his debut as far back as December 1974. On the first disc are two performances of works by Beethoven, given on two consecutive days in the summer of 1977 at the Tanglewood Music Festival. Tennstedt’s Beethoven is predictably big of heart and can trace its lineage directly from the mainstream German Kapellmeister style, which readers will be familiar with in recordings by conductors like Schmidt-Isserstedt (especially his cycle with the Vienna Philharmonic for Decca), as well as Karl Böhm, with the shade of Furtwängler always hovering in the background, as opposed to the more ‘driven’ school of interpretations as exemplified by Toscanini. So if speeds in the outer movements of the Seventh Symphony are not as supersonic as either Carlos Kleiber’s or Herbert von Karajan’s, to name two major contemporaries, then thanks to nicely sprung rhythms and an intuitive observation of balance and dynamics, this performance still matches both for excitement. In the scherzo, after the splendour of the trumpet fanfares in the trio has died away, Tennstedt lovingly lingers over the muted strings and low murmurings of the French horn, just as Furtwängler used to do, too. This is, of course, Beethoven playing from a time when historically informed practices barely existed and likewise, as was commonplace then, only the barest minimum of repeats is observed – but the interpretation is still magnificent in its own right and is enthusiastically received by the audience.

Interestingly, there is another performance of Tennstedt conducting this symphony, this time with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, given on 22 November 1989 and which has been released on BBC Legends with broadly the same interpretation, where the audience reaction at the end is a little more restrained (more ‘English’ maybe), but where the greater focus and heft of the BBC radio engineering ultimately deliver a more satisfying listening experience. Therefore, if it is Tennstedt conducting this symphony that you want, then my advice would be to seek out that performance over this one.

The Boston recording of the Seventh Symphony was the second half of an all-Beethoven concert, that started with the Prometheus Overture, followed by the Fourth Piano Concerto with Peter Serkin, who appears the following day for another Beethoven work, the Triple Concerto, which is also featured on this release (the second half of that concert featured the Eroica – which is available in Volume 3 of this series: see review). In this performance, Serkin is joined by Joseph Silverstein and Jules Eskin, the Boston Symphony’s distinguished principal players for a fine performance of the Triple and while it will never displace your own current favourite versions, you would still have considered it a marvellous experience in the concert hall had you been there.

It’s a similar story with the Haydn Farewell Symphony from the second disc of this release, a wonderfully warm and big-boned reading from a couple of years later. If nobody would dare perform Haydn these days in such a style, that is not to disregard the drama Tennstedt finds in this music, nor the sensitivity with which he shapes the symphonic argument; I enjoy it all very much and look forward to hearing the Mozart Symphony No 39 that opened that particular programme, along with Haydn’s rarely heard Sinfonia Concertante that was sandwiched in between the symphonies and is included in Volume 2 of this series (see: review)

I’m not completely sure that the recordings from Tanglewood are ‘official’ releases from original sources, though, the give-away being the presence of the radio announcer, both at the start and at the end of each performance; which reveals these have all probably been taken ‘off-the-air’ rather than directly from the radio archives. There is certainly some improvement in the sound from previous unofficial releases I have heard, but it still has to be pointed out that while the sonics are warm and clear, they are also a little flat, which an a/b comparison with the Boston Symphony and London Philharmonic performances of the Seventh Symphony reveals all too readily.

However, in spite of my caveats above, there is a very real reason why this release is an essential purchase – and that is the inclusion of a performance of Mahler’s First Symphony, from a live radio broadcast with the NDR Symphony Orchestra in 1977. In my Survey of this symphony, I considered over two hundred recordings of this work, both official and unofficial, out of which this NDR recording by Tennstedt was considered to be one of the very top recommendations, as well as being the best of all the various official and unofficial accounts featuring this conductor.

Indeed, there are five other available recordings of Tennstedt conducting this symphony on disc, ranging from the earliest, a live performance with the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1976, to his final one, that was released by EMI on both CD and DVD with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in 1990. All are superb performances and, with the exception of one, very similar in design, timings and interpretation. The exception is the final one in Chicago that is some seven minutes longer than the others and, at a shade just below the sixty-minute mark, one of the longest in the whole catalogue, too. That it doesn’t sound so slow is in part due to the concentrated playing of the orchestra as well as the magnetism of the conductor with this composer, the whole reading having taken on an almost Horenstein-esque darkness, Tennstedt viewing the symphony seemingly through the prism of Mahler’s later works. It’s an absorbing listen on CD, as well as an absorbing watch on a well-directed DVD, but I would argue that it’s Tennstedt at his most interesting rather than his best. In my opinion, therefore, if you want to hear Tennstedt at his best in this work, then the earlier recordings, of which this NDR live radio taping is one, are the ones you must seek out. As noted, they are all very similar, lasting around the fifty-four minute mark and also noteworthy, in light of the conductor’s later readings of Mahler, for being surprisingly ‘straight’.

Here in these earlier recordings, Tennstedt reveals himself to be almost the ideal conductor for Mahler’s First Symphony, as there is a magic about his treatment of this score that is quite unique. Few other conductors, if any, have found so much warmth and poetry in the opening measures of this symphony, evoking the soft awakening of nature, with its miniature trumpet fanfares suggesting a magical child-like world, where droplets of harp and isolated bird calls are floated almost literally on the still early morning air, before the Wayfarer’s music ambles along with unaffected good humour under Tennstedt’s baton. His, then, is truly a special achievement, that combines an almost Kubelikian sense of ‘rightness’, coupled to an air of unaffected joy and childlike rapture that is quite remarkable – in short, it is the polar opposite of the approach of Tennstedt’s predecessor at the helm of the London Philharmonic, Georg Solti, especially in his first recording with the London Symphony Orchestra. With that comparison, comes criticisms with Tennstedt’s interpretation, since it lacks that sense of apocalyptic fury that Solti is able to unleash at the beginning of the final movement, as well as the pile-driving excitement at the end of the whole work, to cite a couple of examples. This may be a drawback for some, as it was to me the first time I listened to the earlier studio recording, too many years ago to declare in public. Likewise, Tennstedt is also unable to tease out the local colour in the music of the central movements in the way that Bruno Walter and Kubelík were always almost effortlessly able to do, as well as many of the Eastern European bands who have recorded this symphony over the years.

Nevertheless, I don’t want to make too much of this – a Tennstedt-led Mahler First with the Czech Philharmonic in great sound could well have been my most favourite version of all, and so in spite of the abovementioned caveats, there is so much magic elsewhere here that I have no qualms in stating that every serious collection should have a Tennstedt-led recording of Mahler’s First Symphony, if not on their shelves, then at least as a download on their hard-drive. For me, as I discovered in the survey, this NDR Symphony Orchestra recording is the best of all the versions with Tennstedt conducting the work currently available.

I would hazard, in light of the scarcity of information stating otherwise, that this was a performance taped ‘live’ in the studio for radio broadcast, since there is next to no audience noise and applause, but there is still that sense of excitement you almost uniquely get during a live performance. In my opinion, this makes the NDR recording a more rewarding listening experience than the same conductor’s EMI studio account and since it is in better sound, as well as being better played than the other live accounts with the Boston Symphony and London Philharmonic Orchestras, that makes it even more recommendable than those accounts as well. In short, it is one of the best recordings of Mahler’s First Symphony you are ever likely to hear.

In conclusion, this “twofer” presents one of the reference accounts of Mahler’s First Symphony, coupled with repertoire that he did not record in the studio that is noteworthy and laudable. Tennstedt devotees will want this disc regardless, but for anyone else interested in Mahler’s First Symphony, this is a mandatory acquisition.

Lee Denham

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.