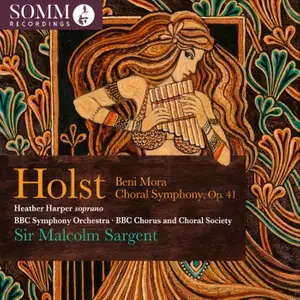

Gustav Holst (1874-1934)

Beni Mora Op. 29 No. 1 (1909-10)

Choral Symphony Op.41 (1923-24)

Heather Harper (soprano)

BBC Chorus and Choral Society

BBC Symphony Orchestra/Sir Malcolm Sargent

rec. August 1956 Kingsway Hall London (Beni Mora), January 1964 Royal Festival Hall London (live broadcast)

SOMM Recordings Ariadne5040 [66]

Holst’s 150th anniversary in 2024 was marked by apparent indifference from the major record companies with none seeming able to summon up the enthusiasm for more than the odd re-release of The Planets. A sterling exception was a handsome two disc set from SOMM which I reviewed here featuring key works in archive performances from important interpreters. This new disc is in many ways a companion to that set with works not included in the earlier collection featuring Sir Malcolm Sargent conducting who also appeared previously. Audio restoration is again in the safe care of Lani Spahr so listeners can be confident that these performances have never sounded better.

“Never sounded better” because both of the works here have appeared on CD before. The suite Beni Mora appears in a 1956 stereo recording from EMI recorded in the Kingsway Hall. Technically this was always a remarkably good recording – I imagine one of the earliest stereo efforts by EMI who clearly thought well enough of it artistically as well as technically for it to appear on a very early CD as well as part of EMI’s 6 disc “Holst – The Collector’s Edition”. In that set this is marked as a “1988 remastering”. The companion work is the Choral Symphony Op.41 taken from a BBC off-air broadcast in 1964. Given that providence the mono sound is perfectly serviceable but clearly of a more ‘historic’ or ‘archive’ nature. The same recording appeared some years ago on the Intaglio label where it was coupled with a live Boult/LPO version of the Choral Fantasia. These new incarnations sound as good as these recordings ever have but not transformatively so [Spahr has eliminated a persistent hum that is present on the Intaglio release] hence if collectors have either or both the earlier iterations it is not necessary to duplicate. SOMM’s presentation is as ever immaculate and attractive and better than previous notes accompanying these performances. Importantly texts for the symphony are included – absolutely vital given the wordy and dense nature of the original Keats poems.

As far as I could see, there is no information given as to the source recording that Lani Spahr has used for Beni Mora. Listening carefully on headphones I was aware of what sounds like a very quiet surface noise ‘swish’ that I associate with an LP source. In no way does this distract from the listening pleasure but it does suggest that the original master tapes have not been used. In both scores Sargent proves to be a very dynamic and successful interpreter. The suite pre-dates The Planets while the symphony is later but both scores incorporate and utilise compositional and musical gestures that are highly characteristic of Holst’s finest work. These include ostinato-like use of melodic and rhythmic fragments, long pedal notes under changing chords, musical lines shaped by non-standard scales and use of complex meter time signatures. In Beni Mora – subtitled “Oriental Suite” this does represent verge on picture-postcard musical images but Holst’s skill with the orchestration and the richness of the writing lifts it well above any accusations of light music novelty. Imogen Holst points out that it was Holst’s first attempt at music for entertainment in a decade and she calls the orchestration “a good rehearsal for the Planets”. In the liner note to this disc Simon Heffer notes that Sargent’s performance is one of the fastest on disc whose effect is; “to showcase a sharp penetrating work with a sense of freshness given by playing that relays the power….anew”. I would say that is a very fair summary of this performance. On a technical level I was struck by how well the detail of the orchestration is caught and apart from a rather large-tea-tray sounding gong, how well the percussion in particular sounds. The most striking movement has always been and remains the third “In the Street of the Ouled Nails”. Holst encountered a musician playing a four note tune played on a bamboo flute for more than two hours during a holiday to Algeria. In the suite this becomes a flute figuration repeated unchanged for 163 bars. Making any claims that this is a kind of proto-minimalism is too far-fetched, but the obsessive repetition – especially at Sargent’s urgent tempo is genuinely compelling.

At the opposite end of the scale in terms of size and ambition is the Choral Symphony Op.41. Running to 51 minutes in this performance, this is Holst’s most ambitious, largest scale work with orchestra (excluding some of the operas). Of course, The Planets shares a very similar run-time but that is a suite in seven movements which is not trying to reconcile the disparate elements of symphonic form, extended choral settings and the use of [famous] poetry which received wisdom would think unsuitable. From its premiere, the reception of the work was mixed – even among the composer’s friends and supporters although Holst himself came to believe it was one of his finest creations. As so often, Imogen Holst is one of her father’s harshest critics although she acknowledges there are passages of blazing brilliance alongside more effortful pages. Sargent’s skill is to emphasise the strengths while minimising the weaknesses. Interestingly this is not just a case of keeping things moving. Whatever Holst’s belief in the work it had to wait 50 years for its first commercial recording which was by Holst stalwart Sir Adrian Boult for EMI with the LPO and chorus with Felicity Palmer singing the demanding solo soprano part in 1974. By timings alone Boult is significantly faster in the opening Prelude: Invocation to Pan and Song and Bacchanal while Sargent allows the ‘slow movement’ Ode to a Grecian Urn to flow considerably more quickly. The closing two movements are very similar timing-wise. The EMI recording – vintage analogue made in the Kingsway Hall by the A-team of Christophers Bishop & Parker – is unsurprisingly better than the off-air mono afforded Sargent. But the ear quickly adjusts to the relative limitations of the radio broadcast and in fact the BBC engineers made a good job at allowing detail to register and the overall balance between the busy chorus writing and the heavy orchestration is not bad. Likewise the solo work of Heather Harper is well caught and her singing is insightful and sensitive – indeed of the 4 sopranos to have recorded this role; Lynne Dawson and Susan Gritton sang for Hilary Davan-Whetton on Hyperion and Andrew Davis on Chandos respectively after Palmer for Boult – I like Harper’s all-round performance most.

Sargent was famously loved by amateur choirs and certainly he galvanises the combined BBC Chorus and Choral Society into dynamic action. Violist Bernard Shore wrote; “He is able to instil into the singers a life and efficiency they never dreamed of. You have only to see the eyes of a choral society screwing into him like hundreds of gimlets to understand what he means to them.” This is particularly valuable in the opening movements which require the evocation of Bacchic delight. [Imogen Holst is rather harsh here too!; “These highly strung revellers, “all madly dancing” with “faces all on flame”, seem able to keep up their energetic seven-eight on nothing stronger than soda water”] Sargent’s choir sound more unbound than Boult’s well-drilled if slightly too well-behaved group. That said, the ‘wordiness’ of Keats’ texts and the complexity of the choral writing will always mitigate against this being a work that can be frequently programmed by any except the finest choirs with access to large professional orchestras.

Overall this is a valuable restoration (in every sense) to the catalogue of as fine a pair of performances of these two works as any even allowing for their age and – in the case of the symphony – the compromised audio. In part due to a discography that includes few recordings made in the finest sound, Sargent’s enduring legacy is relatively small compared to contemporaries such as Boult, Beecham or Barbirolli – these recordings show just how inspiring he could be.

Nick Barnard

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free