Herbert von Karajan (conductor)

Live in Berlin 1953-1969

rec. live, various dates, 1953-1969, various venues, Germany

Mono/Stereo

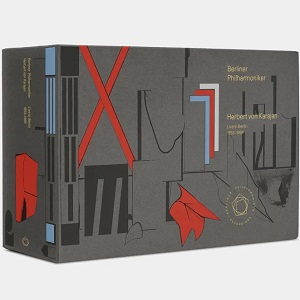

Berliner Philharmoniker BPHR240291 SACD [24 discs: 1466]

This highly-anticipated release from the Berliner Philharmoniker’s in-house label is exciting for many reasons: First, most of these 24 discs consist of new, previously unpublished material, among them select repertoire that Karajan had never recorded elsewhere, such as Ligeti’s Atmosphères and Liebermann’s Capriccio for Soprano, Violin and Orchestra. Secondly, these performances are without exception radio broadcasts, allowing the audience a glimpse of Karajan and the Berliner Philharmoniker at its most spontaneous and organic. Until the present, we have never seen a live, uncut release by this extraordinary partnership that covers such diverse repertoire and wide timespan. The orchestra’s own label was able to obtain the recorded live broadcasts from the former RIAS and SFB radio stations to digitize them, in high resolution no less, and publish them for the first time since these concerts were first played. Most of the recordings here were captured in mono sound, with only a few items from 1967-1969 available in stereo; the sonics are uniformly clean, clear, and allow us to obtain a vivid impression of the Berliner Philharmoniker’s legendary capabilities under its perhaps even more legendary former director for life. The contents of the release include a large box and 128-page hardcover book designed by sculptor/painter Thomas Scheibitz, extensive essays by Karajan biographer Peter Uehling (Karajan’s Radio Recordings: Designs for a Time of Reconstruction), music publicist James Jolly (Karajan in Concert) and more. Since my colleagues John Quinn and Philip Harrison have already done a joint review of this release, the present article distinguishes itself by constituting the thoughts and impressions of a single listener going through the box set’s contents in chronological order, and for the sake of readability and convenience, the following reviews of each of the 24 discs will be organized in that manner.

CD 1 ꞏ MONO: CONCERT NO. 1 ꞏ 8 September 1953 ꞏ Titania-Palast, Berlin

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 in E flat major, Op. 55 “Eroica”

This is a supremely powerful reading of the “Eroica” symphony. Compared to Karajan’s studio account with the Philharmonia on EMI, recorded in 1952 (review here), this radio broadcast has significantly more presence, with the sonic image presented more upfront. The Berliners also have a richer string and brighter brass section by far, in comparison to the Londoners. Timings are very similar between the two renditions, with only the Marcia funebre: Adagio assai second movement having an almost one-minute deviation, with the Berlin Philharmoniker being the broader performance. The wide-open, brilliant trumpet tone that Karajan cultivated with his orchestra (and on later recordings with the Wiener Philharmoniker as well) is already on full display here, notably at the recapitulation of the Allegro con brio (CD 1, track 1, 9:09). The fast movements are especially successful in this performance, with the immense momentum built via perfectly controlled and sustained tempi, one of Karajan’s hallmarks. Although the mics are very much overloaded by the timpani at the conclusion of the symphony (CD 1, track 4, 12:21-12:28), what a glorious testament to the performance’s intensity this is.

CD 2 ꞏ MONO: CONCERT NO. 2 ꞏ 22 November 1954 ꞏ Hochschule für Musik, Berlin

Ralph Vaughan Williams: Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis

Those who follow Karajan/Philharmonia’s work will know that the pair had recorded this immensely popular Vaughan Williams piece in the 1950s with EMI as well, including at least once in 1954 (review here). However, the present recording is the only commercially available version of the piece that the maestro recorded with his Berliner Philhamoniker. Timing-wise, at 13:15, it’s more than a minute and a half quicker than his EMI rendition, imbuing a slight feeling of wariness with the work’s usually serene atmosphere. As in the “Eroica” symphony, the Berlin strings here sound fuller and cleaner compared to their Philharmonia counterparts, and while the treble could come off a tad on the harsh side at the loudest dynamics, the overall sonics are truly impressive given the age of the broadcast.

CD 2 ꞏ MONO: CONCERT NO. 3 ꞏ 22 February 1955 ꞏ Hochschule für Musik, Berlin

Richard Wagner: Tristan und Isolde, Prelude and Liebestod

Karajan had a strong affinity for Wagner’s music dramas, including Tristan und Isolde, of which the Prelude to Act I and Liebestod (Act III) he recorded numerous times throughout his career, including at least two more versions with the Berliner Philharmoniker, in 1974 on EMI (review here), and in 1984 on DG. Compared to those later stereo (and studio) efforts, the present broadcast has less sonic depth, clarity and dynamic range, which is to be expected given its vintage. Musically, though, this is a truly passionate performance, and a very polished one as well. The woodwinds, in particular, shape the famous “Tristan motif” very expressively, with the Clarinet I taking the spotlight at the beginning of the Liebestod (CD 2, track 1, 11:49-12:19). The strings are delectably lush throughout, and the first outburst before the long chromatic sequence (CD 2, track 1, 15:29) has both power and clarity in spades, while the later, even grander climax (CD 2, track 1, 16:30) is shattering in force but doesn’t sound harsh in the slightest – the orchestral balances are well-preserved with all instrumental groups reinforcing the stirring theme in the violins. This is a sensationally played and engineered performance.

CD 2 ꞏ MONO: CONCERT NO. 4 ꞏ 21 January 1956 ꞏ Paulus-Gemeinde Zehlendorf, Berlin

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Concerto for Piano and Orchestra in D minor, K. 466, Wilhelm Kempff, piano, Symphony No. 41 in C major, K. 551 “Jupiter”

In 1956, Karajan had also recorded the K. 466 concerto another time, though with the Philharmonia and Clara Haskil at Salzburg’s Mozart Week (review here). Compared to that Mozarteum performance, the present broadcast has fuller sonics, with the piano featuring a sparkle that lets it sing above the orchestra’s sensitively played accompaniment. It’s worth noting that both Haskil and Kempff opted to perform presumably their own cadenzas in the first movement, a departure from the more common Beethoven version that had been preferred by pianists from Schnabel to Fischer and Richter. The Romanze has the Berliner Philharmoniker at their gentle best, with light textures throughout that illuminate the solo piano beautifully, while the Allegro assai has Kempff and the orchestra feeding off each other in both the movement’s tempestuous first and jolly second themes. The rich sonority that Karajan and the Berliner Philharmoniker favours here is a great match for Kempff’s equally burnished tone, and this consistency in tonal conception makes this performance a standout.

The “Jupiter” symphony was also recorded numerous times through Karajan’s career, notably with the Berliner Philharmoniker in 1978. The main difference between that later version and this one is that the 1978 take features an exposition repeat in the Allegro vivace, which is omitted here, not an uncommon decision for radio performances. The 1956 reading is also more spirited in both tempo and overall pacing in the fast movements, with remarkable gusto from the ensemble in all of its sections. The much more spacious sonic presentation of the 1978 account lends itself a sense of grandiosity that’s absent in this radio broadcast, though many might find the leaner sound of the older take more suited for Mozart’s music, this author included. The incredible fugal writing (five-part invertible counterpoint for the theory aficionados) in the coda of the Molto allegro movement is executed with impressive clarity of phrasing and texture here (CD 2, track 8, 4:59-5:42), and at a breathtaking speed, too. The virtuosity, and more importantly, joie de vivre of the Berliner Philharmoniker under Karajan is on full display, giving us a most gratifying end to a wonderful Mozart disc.

CD 3 ꞏ MONO: CONCERT NO. 5 ꞏ 10 December 1956 ꞏ Hochschule für Musik, Berlin

Richard Strauss: Es gibt ein Reich (There is a realm) from Ariadne auf Naxos, op. 60, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, soprano

Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Op. 64

This next broadcast begins with an aria selection from Strauss’ Ariadne auf Naxos, Es gibt ein Reich (There is a realm). This is Ariadne’s monologue when she’s lamenting having been abandoned by her faithless lover on a desert island, while waiting alone for the messenger of death. As expected, the great Schwarzkopf sings beautifully here, with her luscious voice effortlessly soaring above Karajan and the Berliner Philharmoniker’s gentle accompaniment. It’s worth pointing out that Karajan and Schwarzkopf had actually recorded the opera with the Philharmonia Orchestra just two years earlier for EMI – the first studio version of the work ever put on tape, in fact.

The Tchaikovsky symphony here represents another striking performance, one captured in better sound than other commercially available recordings of the piece by the same conductor in the 1950s, including the 1953 live performance in Turin with the Orchestra Sinfonica di Torino della RAI and the 1954 studio recording with the Philharmonia for EMI, as those two have a rather distant and at times even faint sonic image. The white-hot intensity of Karajan’s interpretation and his orchestra’s execution are exhibited in full splendour here, though the strings do sound a bit astringent as they approach louder dynamics, as towards the end of the second theme of the Andante – Allegro con anima (CD 3, track 2, 6:43-6:50), no doubt due to the limitations of the recording capabilities available at the time. Sonic limitations notwithstanding, one could definitely obtain a salient impression of Karajan’s penchant for richness of sonority here: the strings are full, the brass big-toned, the woodwinds glowing. The Andante cantabile, con alcuna licenza is gorgeously paced, with a liquid-smooth horn solo from the unfortunately uncredited principal chair. Things continue to impress in the Valse. Allegro moderato, with some crisp playing from the woodwinds and strings in the Trio section (CD 3, track 5, 1:38-3:16). The concert of course ends with the symphony’s stirring Finale. The introduction’s motto theme is supposed to echo its initial appearance at the very beginning of the symphony, down to the time signature, tempo marking and rhythmic values used by Tchaikovsky, and Karajan takes care here to ensure that the sustained tempo and smooth phrasing matches what we first heard. The entire ensemble is virtuosic throughout the movement proper, marked Allegro vivace (alla breve).The coda is as thrilling as it should be and the sonority culminating at the gigantic dominant chord (CD 3, track 6, 9:46-9:51) is truly worthy of the conductor’s acclaim for tonal polish. The final peroration based on the motto theme, led by the trumpets (CD 3, track 6, 10:40-11:16) is triumphantly gratifying – Karajan always likes to ensure that the fff trumpets are truly soaring above and beyond the rest of the orchestra here, whether in his 1975 recording with the Berliner Philharmoniker or the 1984 account with the Wiener Philharmoniker, both of which are on DG. It’s a personal requirement of mine that a great interpretation of this symphony must end with trumpets that sound like these, as it’s such a powerful moment that finally allows us to bask in glory after an emotional journey of about 50 minutes.

CD 4 ꞏ MONO: CONCERT NO. 6 ꞏ 19 February 1957 ꞏ Hochschule für Musik, Berlin

Sergei Prokofiev: Symphony No. 5 in B-flat major, Op. 100

The Austrian conductor is almost universally acclaimed for his 1969 DG recording of this work (review here and here), considered by many a critic to be among the finest accounts ever of Prokofiev’s wartime masterpiece. While the present performance cannot match that iconic version made twelve years later in sonic presentation, it grants us a rare glimpse into the blazing intensity at which Karajan and his band performed this piece in a live setting. The opening Andante, which takes 13-14 minutes in many recent recordings, is dispatched in just 11:49 here, with Karajan’s signature momentum in the fast sections feeling as relentless as ever, notably in the movement’s thrilling development section (CD 4, track 1, 5:25-6:54). The tam-tam strokes in the coda, although not jump-from-your-seat cataclysmic as they are in the famed DG rendition, are tremendously powerful and don’t take the spotlight away from the rip-roaring brass (CD 4, track 1, 10:19-10:51). Next, the Allegro marcato is almost identical in timing to the DG effort, being just two seconds shorter here. The marcato and staccatissimo markings are observed very closely here indeed, with incisive attacks across the ensemble lending remarkable transparency to such a mighty orchestral sonority. This is no mean feat at all, and this goes to show just how judicious the maestro was about articulation in general, contrary to the common misconception that he was biased towards legato phrasing. Listen to the way the orchestra speeds up and builds from the central section back to the main toccata-like section (CD 4, track 2, 5:39-6:21). What a well-paced and graduated poco a poco accelerando (gradually faster, little by little)! In published interviews with Karajan, he often boasted about his sensitivity to tempo and rhythm, particularly to their steadiness and fluctuations. We’re very fortunate to have numerous testaments of this trait of his on record, then. The ensuing Adagio features plenty of lyrical playing consistent with the overall performance, but the beginning of the movement’s colossal climax (CD 4, track 3, 7:28) sets up a momentum that’s held absolutely steady throughout the episode, a remarkable departure from many performances wherein conductors broaden the pace to create higher tension, when an unyielding velocity actually results in greater sonic impact, as it does to great effect here. Topping off the concert is a charming Allegro giocoso–the odd, “wrong note” A-flat interjections from the Trumpet III (CD 4, track 4, 3:53 and 3:57), could have more presence to better foreshadow the coda, though. The contrasting chorale section (CD 4, track 4, 4:29-4:55) puts the burnished Berliner strings on display, even at a pp dynamic. The coda (CD 4, track 4, 7:43 onwards) is exhilarating: The woodwinds shriek, the harps sweep, the percussion bang and clang, and the brass blast away. All of this is under total control, though, with Karajan and the orchestra maintaining a rock-solid impetus throughout–at the risk of repeating myself, these performers’ ability and more importantly, will to firmly adhere to a set tempo is truly awe-inspiring. Once again, where the temptation to speed up is strong, Karajan and the Berliner Philharmoniker almost always have their sights on loftier ideals. They’re deeply faithful that the virtuosity of their playing and the power of the composer’s score will create a stronger impact than superficial histrionics. Bravissimo, team!

CD 5 ꞏ MONO: CONCERT NO. 7 ꞏ 25 April 1957 ꞏ Hochschule für Musik, Berlin

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125, Elisabeth Grümmer, soprano, Marga Höffgen, mezzo-soprano, Ernst Haefliger, tenor, Gottlob Frick, bass, Chor der Sankt Hedwigs-Kathedrale, Karl Forster, chorus master

Now, we’ve arrived at the first of three (!) Beethoven Ninths found in this box set. Since the other two performances are from 1963 and 1968, comparisons here will be made with the other account that Karajan recorded in the 1950’s instead, namely the one with the Philharmonia for EMI, including the mono (review here) as well as experimental stereo versions of that performance. Sonically, this later radio broadcast has as much presence as the experimental stereo version of the 1955 rendition, albeit with an obviously narrower image considering it was captured only in one channel after all. However, it has a significantly clearer and deeper focus than the mono version of the 1955 effort, which sounds diffuse and thin by comparison. The opening Allegro ma non troppo e un poco maestoso (Quick but not too much and a little solemn) is granitic in strength, with a fullness in the Berliner’s sonority markedly beyond what the British band offered him two years earlier. This is immediately apparent when the orchestra plays in tutti at the first statement of the primary theme (CD 5, track 1, 0:29-1:03). The shattering climax of the movement, where the development culminates in an enormous restatement of the main theme and thereby beginning the recapitulation (CD 5, track 1, 8:10), is aptly overwhelming, though clarity has been carefully preserved here, with the four-note motif in the trumpets and horns crisp and clear (CD 5, track 1, 8:27-8:28). The movement is capped off with a passionate coda, though I’d prefer the closing bars to be at a constant tempo here, rather than being pulled back for an even more powerful finishing blow. This is one of the few places where Karajan prioritized sonic weight over momentum, but I’m not certain that the Berliners needed any help in that regard here, or anywhere else, for that matter. The Molto vivace (very lively) is a tricky scherzo to pull off, because it’s very brisk in both the scherzo (in ¾ time) and trio (in 2/2) sections – in fact, the middle part is in Presto, and since Beethoven gave both sections of the movement a metronome marking of 116 (to a dotted quarter note and to a whole note, respectively), the contrasting trio is actually more rapid than the main theme, though conductors have always shown a diverse and liberal range of implementations when it comes to the tempo relationships of this movement. Here, Karajan renders the stringendo il tempo (quicken the tempo) from the scherzo into the trio very well (CD 5, track 2, 4:32-4:36), but actually sets the Presto slower than its metronome marking demands as soon as the time signature changes (CD 5, track 2, 4:38). Though not adhering strictly to the letter of the score, I find that this approach effective since it allows the trio to provide the listener some reprieve from the hectic scherzo sections that sandwich it. The Adagio molto e cantabile (very slowly and singing) is breathtaking. The double variations form means that the primary and the secondary themes take turns appearing and reappearing, intensifying in expression each time. Karajan manages the pacing of the movement splendidly well, even as the note values in the melody become shorter, he never allows the music to become restless or agitated – after all, this movement is a long-breathed, songlike counterweight to the symphony’s other three, all of which are plenty hectic already. The finale receives a top-notch reading, as to be expected from the maestro who enjoyed a virtually peerless reputation for his treatment of this movement, one of the most celebrated in the entire orchestral repertoire. Spirited playing and singing abound, and the energy of a live concert is palpable especially in the flexibility of the vocalists’ performances. I appreciate how the grand “Ode to Joy” chorus, or Variation 5 in formal terms (CD 5, track 5, 6:40-7:22), is kept a swift clip throughout so that structurally it feels more like a part of a greater whole rather than an arbitrary climax–there is no request by the composer for this section to be any slower or faster than its lead-up anyway. The final “Freude, schöner Götterfunken!” (“Joy, bright spark of divinity!”) here is immensely powerful, with Karajan, like most conductors, dialling back the tempo generously so that the ensuing Prestissimo (as quick as possible) would be even more impactful, and the symphony concludes with all the adrenaline rush that it should give us indeed.

CD 6 ꞏ MONO: CONCERT NO. 8 ꞏ 25 May 1957 ꞏ Hochschule für Musik, Berlin

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 3 in C minor, op. 37, Glenn Gould, piano

Jean Sibelius: Symphony No. 5 in E-flat major, Op. 82

This next concert is a legendary one – the only recording that Karajan ever made with the iconoclastic Canadian pianist Glenn Gould. While observers might feel that this was an unlikely partnership, the two men actually admired each other deeply, and Karajan once even remarked that “listening to him [Gould], I had a feeling of listening to myself. His way of music-making was so similar to mine.” At first glance, the version included in the present box set might not seem like the only recording of this concert, as Sony Classical had also issued its own in 2008, with the same coupling of Beethoven and Sibelius, a closer inspection of the recording dates reveals that the present recording is in fact from the performance (25 May) a night before the same program was recorded for Sony’s release (26 May). Compared to that version, this Berliner Philharmoniker Recordings release unfortunately sounds more muffled and claustrophobic, with less sense of space. Gould’s piano tone is reproduced at a similar level of fidelity to Kempff’s in the aforementioned Mozart recording from Concert No. 4 , which is to say, pretty remarkable indeed. For a pianist who had a famous, sometimes infamous reputation for his dry, staccato touch, this performance is very well-judged in articulation overall. Rapid runs and arpeggios near the end of the Rondo. Allegro – Presto are executed with the Canadian virtuoso’s trademark clarity, but also plenty of resonance as a result of judicious sustain pedalling. (CD 6, track 3, 6:47-6:54, 8:20-8:40).

The Sibelius Fifth of this concert is quicker-paced compared to Karajan’s 1960 rendition with the Philharmonia, with the beginning movement over a minute shorter here. Although this mono Berliner Philharmoniker account was set down only three years before the EMI one, its shortcomings in the sonic department are very apparent compared to its stereo Philharmonia counterpart. Notably, the brass is rather congested and harsh towards the end of the first movement, where the opening theme takes on its most exalted form, with the full orchestra blazing at ff (CD 6, track 4, 11:45-12:26). It’s certainly not the fault of the performers – if anything, this is a testament of just how overwhelming Karajan and his Berliner’s sonority could be, that even some of the best mono recording capabilities at the time couldn’t come close to doing it justice. The second movement receives a swift reading at just 7:45. This is extraordinary since many modern readings take around 9:30 or more, such as those by Esa-Pekka Salonen/San Francisco Symphony, Mark Elder/Hallé Orchestra and Yannick Nézet-Séguin/Orchestre Métropolitain. The variation of the main theme where the violins enter with eighth notes for the first time (CD 6, track 5, 1:36) is taken at a rather breathless pace, and as the movement hastily builds towards its central climax, I couldn’t help but feel that a more tranquillo, or peaceful, (an actual expressive marking of one of this movement’s sections) take would’ve helped this quasi-interlude serve its role better, flanked by two vigorous movements as it is. Disappointingly but not surprisingly, the same gripe regarding the recorded sound that I had with the first movement returns with a vengeance in the last movement. Again, this is in no way a condemnation of the performance itself – it’s just such a pity that technical limitations in audio engineering at the time marred so many legendary performances by musicians as great as Karajan and the Berliner Philharmoniker. The ensemble’s world-renowned string tone is reduced to wiry, grating scratches here, while the esteemed brass are turned into screeching industrial equipment. I highly recommend listeners to turn their volume knobs down a couple of notches from the point the finale initiates its final buildup (CD 6, track 5, 7:00 onwards), particularly if they’re listening via headphones. That is how offending the captured sound here is. Artistically speaking, this performance, grandiose as it is, is also not preferable over the Philharmonia one on EMI, with the nail in the coffin being a somewhat rushed conclusion, where Sibelius curiously spaces out the six final chords in a highly deliberate way. The later stereo recording takes full advantage of its more spacious soundstage and allows the sonority of each chord to dissipate before another one is attacked, while this mono one feels scrambled and haphazard in its pacing, robbing the epic ending of its finality. Despite being a rare historical document, this concert broadcast is not to be recommended, especially considering the excellent accounts of this work that Karajan made later, beginning with the Philharmonia/EMI production.

CD 7 ꞏ MONO: CONCERT NO. 9 ꞏ 20 September 1959 ꞏ Hochschule für Musik, Berlin

George Frederic Handel: Concerto Grosso in D major, Op. 6 No. 5, HWV 323

Rolf Liebermann: Capriccio for Soprano, Violin and Orchestra, Irmgard Seefried, soprano, Wolfgang Schneiderhan, violin

Robert Schumann: Symphony No. 4 in D minor, Op. 120

Concert No. 9 is another special one, as it combines two composers Karajan recorded numerous times throughout his career with one who is largely unknown, let alone in the Austrian maestro’s discography. Rolf Liebermann is a Swiss composer noted for his eclectic mix of compositional techniques, combining elements from Baroque, Classical, and even twelve-tone styles. Liebermann is not to be confused with Lowell Liebermann, American composer of the well-loved piano suite Gargoyles. The Handel here is given a fierce reading, with string tone so sumptuous, especially in the cellos and basses; one wonders if they’re listening to a Brahms symphony instead, case in point being the ending chord of the Presto (CD 7, track 3, 2:20-2:23). Karajan recorded the same Concerto Grosso, along with No. 1-4, 6-12 with the Berliner Philharmoniker on EMI in the late 1960’s, which offers a much richer sound than what we have here, and in stereo, of course.

The Liebermann is an interesting work, to say the least; remarkably, the piece was just published in 1958 by Universal Edition, with its premiere given by Markevitch and the Orchestre des Concerts Lamoureux on 1 March, 1959, barely half a year before Karajan and the Berliner Philharmoniker playing it in this concert. It’s certainly fascinating to hear the famed conductor and ensemble performing a piece so contemporary to them, and it being sandwiched by two traditional warhorses of the standard repertoire at that. Seefried and Schneiderhan both give virtuosic performances here, with seemingly endless runs in both the soprano and solo violin parts.

After the abstract Capriccio, hearing the unison As at the beginning of Schumann’s Fourth is very refreshing. Like many other pieces found in this box set, Karajan also recorded this work for EMI around the same time as these radio broadcasts. This time, his studio effort actually preceded the present concert, with it being set down in 1957 with the Berliner Philharmoniker instead of the Philharmonia, the usual group that he recorded with EMI at the time. At that point, the maestro had already been appointed principal conductor of the top German orchestra. I’m glad to report that the broadcast recording here sounds clearer, fuller and more balanced than its older EMI sibling. The opening Ziemlich langsam – Lebhaft (rather slow – lively) is given a fiery treatment, with a rich but very transparent orchestral sonority that allows the exposition section (starting from Lebhaft) to proceed along with great momentum with impressively precise articulation (CD 7, track 8, 2:05-3:23), with staccatos, accents and sforzandos rendered with phenomenal clarity. A very brief slow movement, the Romanze: Ziemlich langsam recalls the theme of the first movement’s introduction in its own beginning, and Karajan and his ensemble are careful in conjuring up the matching atmosphere, beautifully blending the strings and woodwinds in this suspenseful section (CD 7, track 9, 0:47-1:35). Next is the Scherzo, with the same Lebhaft marking that all three quick movements of this symphony receive. Notably, Karajan takes the Trio section at a much more leisurely speed than its surrounding scherzo sections, even though Schumann never indicated a tempo change. Even if it was advisable to relax the tempo to create a stronger contrast, I’d rather the difference not be as jarring as it is here. The last movement, Langsam – Lebhaft also recalls themes from the first movement, making this symphony a very integrated work, especially for its time. The Berliners play with gusto as usual, but I want to point out a neat example of their virtuosity and integrity, for which they are rightly revered. The dotted rhythms in the first part of the development section are executed with spot-on precision, a remarkable feat given that the composer gave this motif a canonic treatment across the strings and woodwinds, and for a minute straight this rhythm is relentlessly repeated (CD 7, track 11, 2:23-3:25). Despite changes in dynamics and stresses, the orchestra never lets these rhythms slacken. Sensational! The coda is as exhilarating as one would expect, with tremendous tone from the brass and strings, in particular – listen to the final chords and tell me if that sonority isn’t worthy of a Bruckner symphony (CD 7, track 11, 6:31-6:45). This repertoire finds Karajan and his band at their best, indeed, whether you’re a fan of their sound or not. I personally find them glorious here, and will gladly return to this disc if only for the Schumann performance.

CD 8 ꞏ MONO: CONCERT NO. 10 ꞏ 10 October 1961 ꞏ Hochschule für Musik, Berlin

Johannes Brahms: Symphony No. 4 in E minor, Op. 98

Claude Debussy: Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune

Maurice Ravel: Daphnis et Chloé, Orchestral Suite No. 2, Symphonie chorégraphique on a scenario by Mikhail Fokin

This next concert brings us to the 1960’s. Although the Brahms here is still in mono and cannot hold a candle sonically to the 1963 stereo version that Karajan and the Berliner Philharmoniker recorded for DG just two years later, it’s still remarkable for its age. The opening Allegro non troppo (not but too fast) displays the gorgeous string phrasing for which these performers were highly lauded, though it’s a pity that that sonic limitations made the violins sound rather brittle as the passionate primary theme unfolds (CD 8, track 1, 0:46-1:31). As a telling sign of the maestro’s structural grasp, I appreciate how Karajan saves the highest volumes for the fervent coda – the true climax of the movement – instead of going all out when the fortissimi first begin appearing in the development section (CD 8, track 1, 3:38 and 4:35). The Andante moderato (walking speed, moderately) acts as a welcome counterbalance to the rest of the symphony, which consists of three quick movements. The playing is generally at the high level that one would expect from these performers, though a small but obvious slip in the Horn in E’s statement of the main theme (CD 8, track 2, 1:52-1:53) gently reminds us that the Berliner Philharmoniker is made up of mortals after all, and that we’re listening to an unpatched radio broadcast. What a lavish string tone towards the end of the middle section, though (CD 8, track 2, 7:48-9:22)! The signature Karajan/Berlin sound is largely built upon a massive bed of well-blended strings with intense vibrato in the violins and a deep foundation in the basses, and this is a perfect moment to savour it, audio limitations notwithstanding. Our Allegro giocoso (fast and playful) that follows shows us another classic Karajan moment – something so agile and quick-footed shouldn’t be able to have this much weight and impact, but such is Karajan and his orchestra’s refinement that it allows them to propel their gargantuan wall of sound forward while maintaining effortless control. There is a spot where vocalizations are clearly heard amidst the action, mimicking the melody in the strings, though they don’t quite sound like the conductor’s voice to me (CD 8, track 3, 1:56-1:58). Very curious! The symphony concludes with a no-holds-barred presentation of the Allegro energico e passionato (fast, energetic and passionate). Talk about energy and passion – the Berliners are on fire here, starting right with the eight notes of the main theme (CD 8, track 4, 0:01-0:14), which are about to undergo thirty variations in this passacaglia form (varying and/or developing themes over a recurring bass pattern of fixed length). I think Karajan’s decision to not deviate too much from the basic tempo here is very effective. After all, here, like in many passacaglias, the composer only wrote one basic tempo for the entire movement, and even made it a point to indicate that quarter notes should maintain the same speed when the music shifts from 3/4 time to 3/2 at measure 97 (CD 8, track 4, 3:00-3:08). The later variations show Karajan and the Berliners at their most ferocious (CD 8, track 4, 7:09-7:22), and the coda (CD 8, track 4, 8:49 onwards) is positively devastating. My only gripe is that I could’ve done without the slowdown at the final bars, where the conductor allows the orchestra to take a huge physical as well as musical breath before blowing out the ultimate chord (CD 8, track 4, 9:39-9:45). I prefer a steady momentum throughout the coda, as its sense of relentlessness and inevitability would’ve made the ending all the more tragically powerful. Still, this is a virtually negligible price to pay for an otherwise colossal reading of Brahms’ masterpiece.

The Debussy and Ravel pieces in this concert have both been recorded by Karajan and the Berliner Philharmoniker in the 1960s, in stereo and therefore much fuller sound. The playing here is plenty refined, though the colouristic orchestration of this repertoire really only comes alive on a wider soundstage, so I strongly prefer those studio accounts over the performances here. Interestingly, while the Daphnis et Chloé, Orchestral Suite No. 2 is nearly identical in timing across the two versions, the Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune here is almost a full minute longer than these performers’ 1964 take (9:32 compared to 8:39).

CD 9 ꞏ MONO: CONCERT NO. 11 ꞏ 1 March 1963 ꞏ Hochschule für Musik, Berlin

Johann Sebastian Bach: Magnificat in D major, BWV 243, Maria Stader, soprano, Christa Ludwig, mezzo-soprano, Luigi Alva, tenor, Walter Berry, bass, RIAS Kammerchor, Günther Arndt, Chorus Master, Edith Picht-Axenfeldt, harpsichord, Helmut Schlövogt, oboe d’amore, Fritz Wesenigk, Herbert Rotzoll, Karl Pfeifer, piccolo trumpets

Karajan recorded Bach’s Magnificat in 1979 in the studio, then again live at the 1984 New Year’s Eve Concert with the Berliner Philharmoniker. This radio broadcast, compared to those later accounts, lacks presence and warmth largely due to its mono sound, but certainly not passion or drive. The opening Chorus: Magnificat anima mea has the RIAS Kammerchor bellowing in a spirited way that I find more exciting than the Chor der Deutschen Oper Berlin in the 1979 recording. A note about the cast of this concert: at first, I found it curious that the solo alto in this performance isn’t credited like the other four of her colleagues. As I got further along and heard more movements, I think it dawned on me what they did here. To my ears, it sounds very much like the soprano in Et exsultavit anima mea doubled the solo alto part in Esurientes, which is to say that the legendary Christa Ludwig actually sang both the Soprano II as well as Alto roles in this performance. That is more than fine by me given how much I like her other work, but where does that leave us with movement 10, Terzetto: Suscepit Israel? As its title suggests, that piece is written for three voices, and we clearly do hear all three of them here, so what exactly was the arrangement? Did they just appoint a chorus member from the RIAS Kammerchor to take on the third part, and if so, why didn’t they credit her? Fortunately, this casting mystery wasn’t the only thing that raised my eyebrows about this performance, as the exalted singing and playing certainly did as well. The chorus’ powerful yet utterly transparent blend is truly impressive in the concluding Chorus: Gloria Patri, especially the first half (CD 9, track 12, 0:01-1:31), while the Berliner Philharmoniker’s seemingly bottomless string tone gets to enjoy the spotlight at the very end as well–listen to that lusciously rich reverb after Karajan cuts off the final chord (CD 9, track 12, 2:17-2:21)!

CD 10 ꞏ STEREO: CONCERT NO. 12 ꞏ 15 October 1963 ꞏ Philharmonie, Berlin

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125, Gundula Janowitz, soprano, Sieglinde Wagner, mezzo-soprano, Luigi Alva, tenor, Otto Wiener, baritone, Chor der Sankt Hedwigs-Kathedrale, RIAS Kammerchor, Günther Arndt, chorus master

Welcome to the second of the three Beethoven Ninths featured in this box set, and the first stereo recording of the box set. This performance is special among its peers here since it has the distinction of being a document of a historical event, namely the house-warming concert for the then highly-anticipated opening of the Berlin Philharmonie, one of the most famed concert halls built in the 20th century. The iconic Berlin landmark was designed by the architect Hans Scharoun, and Karajan himself was heavily involved in the project. The recorded sound here, thanks to being in two channels, has a soundstage that is noticeably deeper and wider than the previous Ninth in this release– I wonder if the then-brand-new hall contributed to this as well. The difference is immediately apparent at the initial orchestral tutti of the Allegro ma non troppo e un poco maestoso (CD 10, track 1, 0:28). There is also an extra sense of urgency in the same movement, with the last build-up in the coda, especially, accumulating tension and momentum without excessive slowing down for more sonic impact (CD 10, track 1, 13:58-14:58). The Molto vivace is also given the turbo treatment here, being dispatched in just 10:16 compared to 11:05 in the 1957 concert. The terraced dynamics of the scherzo are handled particularly well here, with sudden shifts between forte and pianissimo as well as piano and fortissimo clear as day, and without having to sacrifice momentum to render them, either. The slow movement, Adagio molto e cantabile, features the sumptuous string tone that is one of most salient recurring themes throughout the present collection (and indeed, most of Karajan’s recorded legacy) in higher fidelity than ever, perhaps once again thanks to the Philharmonie’s acoustics. The onset of the second theme (CD 10, track 3, 2:38) is a wonderful spot to relish this. The finale is unfortunately not off to a good start, with the rest of the orchestra entering about an eighth note later than the timpani, and the trumpets flubbing the first of the two high As in the Presto opening outburst. As the cellos and double basses respond with the recitative theme, the right channel somehow drops off for a second (CD 10, track 4, 0:14). I wonder what technical issue caused this, as this is a mono recording and is as such supposed to only have one audio channel? As the themes from the first three movements alternate with the aforementioned recitative in the low strings, I wish Karajan had observed the abrupt tempo shifts here more faithfully. Instead, he often transitions from one to another, like when the cellos and double basses slow down dramatically from Tempo I to smoothly merge into the Adagio cantabile (CD 10, track 4, 1:24-1:46), or when they blatantly ignore the Tempo I. Allegro. marking as they emerge from that slower episode (CD 10, track 4, 2:00). The “Ode to Joy” theme is sublimely shaped here as it undertakes its three variations, each of which exuding greater strength and jubilation than the last (CD 10, track 4, 3:09-6:29). The Presto then returns with the strikingly dissonant chord more potent than ever, now with the strings joining in, and the timpani ahead of the orchestra the way it’s actually supposed to be this time, as per the composer. The “Turkish march” variation on the “Ode to Joy” theme (CD 10, track 5, 3:28-5:03) is shaped with an razor-sharp focus on tracing a long line that doesn’t fall off until the most iconic section of the symphony, the climatic chorus, is over almost two minutes later (CD 10, track 5, 7:23). Karajan’s ability to choreograph, generate and sustain momentum within a work’s structure often reminds me of the Heinrich Neuhaus quote about his prodigious student, Sviatoslav Richter: “[Richter] treated each composition like a vast landscape which he surveyed from great height with the vision of an eagle, taking in the whole and all the details at the same time.” Here, the maestro and his ensemble accomplishes this largely via meticulous attention to dynamics, but more importantly through their uncanny ability to adhere to a well-judged tempo, regardless of the complexity of the passages. The choral forces here give a sprightly reading of their highly challenging, pun intended, parts. The sopranos, in particular, hit their upper ranges effortlessly, as does Janowitz with her high Bs at “dein sanfter flügel weilt” (thy gentle wings abide) (CD 10, track 5, 15:49-15:53). The final Prestissimo and push to the end has the Berliner Philharmoniker, the four soloists and the two choirs at their most virtuosic. A special commendation must be awarded to the timpanist here, who is incredible for being able to render his very nuanced part with such spectacular prominence, clarity and fullness of tone. To put it into perspective, his strokes and rolls bounce between eighth notes and quarter notes, just quarters, just eighths, quarters and eighths, as well as quarter note sextuplets–all of this rendered with the entire orchestra blasting away with the greatest force and at the fastest tempo marking possible (CD 10, track 5, 17:21-17:36). Bravo! Or shall I say, bravi instead, as all on stage that momentous evening deserve to be heartily congratulated.

CD 11 ꞏ MONO: CONCERT NO. 13 ꞏ 5 May 1964 ꞏ Philharmonie, Berlin

Richard Strauss: Concerto for Oboe and Small Orchestra in D Major, Lothar Koch, oboe

Four Last Songs, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, soprano

Now, we have an all-Strauss concert. Spread over two discs, the first disc pairs the Bavarian composer’s ever-popular, late oboe concerto with his even more popular, even later masterpiece of four Lieder. The first piece is interesting in that it’s called a concerto at all, instead of something like concertino, given its relative brevity of only about 24 minutes, and the fact that it was scored for solo oboe and an orchestra of just 2 flutes, cor anglais, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns and strings. Its almost chamber music-like textures are a far cry from the epic symphonic poems that Strauss created a reputation for himself with much earlier on in his career, which embodied Austro-Germanic late-romanticism at its most extravagant. Koch, our soloist here, is one of the two principal oboists of the Berliner Philharmoniker during the Karajan era, and I find his tone is very distinctive – it has a lush, cantabile, full of generous vibrato. The rapidly descending 32nd notes that permeate the second theme of the Vivace – Allegro are silky smooth, and Koch doesn’t lose the interspersed cheeky staccatos either (CD 11, track 1, 2:21-4:14). The second movement, Andante allows the soloist to fully centre stage, as the gentle and sparse accompaniment spotlights their soaring lyricism and enables it to fully bloom, as it does here right from the oboe’s first entry (CD 11, track 2, 0:09). The finale is a Vivace – Allegro that lets the soloist strut their stuff. Quick runs, rapid figurations and articulations of various kinds give them quite a workout, and one mustn’t forget that this concerto has all three of its movements linked together without pause, so our oboist can’t really catch a break either. Strauss slotted in a brief but flashy cadenza between the Vivace and Allegro (CD 11, track 3, 3:37-4:11), and Koch executes it flawlessly, without any evidence of having broken a sweat. The ending is particularly exciting because it’s one of the few places in this piece that calls for ff for all involved, but unfortunately Koch’s colleagues fail to land the final chord on the end of his run and end up being ever-so-slightly late. A very small nitpick about a very fine performance, to be sure.

In the catalogue, Schwarzkopf has not one, but two legendary accounts of Strauss’ Vier Letzte Lieder (Four Last Songs) to her name: The first one in 1953 with the Ackermann/Philharmonia, the second one in 1965 with Szell/Radio-Symphonie-Orchester Berlin. The present radio broadcast ranks between those two in terms of audio quality, with deeper and wider presence compared to the 1953 version but a narrower and thinner soundstage than the 1965. She sounds lovely in the opening “Frühling” (“Spring”) as she does in those two studio readings, her soprano voice soaring freely above the orchestra at all dynamics. Listen to the breathtakingly soft “Du..” (you) when Schwarzkopf enters at Etwas ruhiger (somewhat calmer) (CD 11, track 4, 1:43). With all of the instruments at pp and herself at something like a ppp, her voice somehow just radiates through. The next song, “September” has the soprano singing at a lower range in addition to that voice type’s usual tessitura, a test of the soloist’s adaptability and versatility. Schwarzkopf never lacks presence across the entire spectrum demanded by this Lied, and her opening phrase demonstrates her fullness near the middle C range (CD 11, track 5, 0:25-0:37). Schwarzkopf’s melisma on “sehn” (see) in “Beim Schlafengehen” (“When Falling Asleep”) is a fabulous showcase of her sheer intensity (CD 11, track 6, 0:33-0:37). Karajan and the Berliner Philharmoniker do their job well here, keeping a hushed tone and setting the stage for her. Notably, the violin solo at Sehr ruhig (very calm) has such a cantabile expressive quality that had I not been following the score along, I’d have easily mistaken it for an extra line for the soprano that I never knew about (CD 11, track 6, 1:36-2:37). Rounding off this disc, and the first half of Concert No. 13 is an absolutely gleaming “Im Abrendot” (“At Sunset”). The playing and singing continues to be top-notch, with Karajan and Schwarzkopf showing just how exceptionally gifted they were in the lyricism department. When the cor anglais sighingly quotes the transfiguration theme from the composer’s Tod und Verklärung (Death and Transfiguration) after Schwarzkopf sings her valedictory line,“Ist dies etwa der Tod? (Is this perhaps death?), it hit me that there probably isn’t a more poignant moment in all of Strauss, and what a blessing it is to have it realized so tenderly here (CD 11, track 6, 4:31-4:43). I hope the audience gave themselves and the performers plenty of time to collect themselves after the last chord of the evening faded into nothingness.

CD 12 ꞏ MONO: CONCERT NO. 13 ꞏ 5 May 1964 ꞏ Philharmonie, Berlin

Richard Strauss:A Hero’s Life, Op. 40

The second half of our concert continues with a symphonic poem that Karajan recorded twice in the studio with the Berliners throughout his career, which are the well-known 1959 and 1985 accounts, both on DG. Sadly, the sound here is vastly inferior to both of those recordings, with its volume level so low that I had to turn the knob on my amplifier a few clicks to the right for comfort. The 1959 studio take has a much more realistic soundstage, thanks to it being in stereo, despite being five years older than this radio broadcast. When the main theme sets off after the introductory flourish in “Der Held” (“The Hero”, also known as Strauss himself), it’s obvious that the dynamic range simply isn’t sufficient for a piece so vivid in its depiction of the protagonist (CD 12, track 1, 0:37-0:47). We’re supposed to have six horns, all the cellos and double basses at ff here, but it sounds somehow tamer than the f at the top of the movement. As another example, listen to the buildup before a grand pause leads us into “Des Helden Widersacher” (“The Hero’s Adversaries”). Here, the full orchestra goes from ff to fff – it’s as if all of the instruments are desperately crying out for more acoustic space to accommodate their collective power (CD 12, track 1, 3:40-4:12). The critics in the next movement are represented by sarcastic woodwinds and mocking tubas – all of which portrayed hilariously by the wind players here, helping the composer mock his opponents right back in a tongue-in-cheek way (CD 12, track 2, 0:00-0:50). Karajan really gets Strauss’ defiant tone when the fanfare comes in courageously to sweep aside the noise of the critics (CD 12, track 2, 3:42). Next we have “Des Helden Gefährtin” (“The Hero’s Companion”), where Strauss depicts his wife, Pauline de Ahna and her character, which according to the composer, is “…very complex, a trifle perverse, a trifle coquettish, never the same, changing from minute to minute.” I wonder if it’s a cause for alarm or just a merry prank that Mr. Strauss slipped in a quote once again from his Tod und Verklärung (Death and Transfiguration) between the violin solos that are supposed to represent Mrs. Strauss here, then (CD 12, track 3, 1:27-1:42). “Des Helden Walstatt” (“The Hero at Battle”), which follows our at times tender, at times odd spousal portrait receives a bravado treatment, with the Berliners expertly recalling music of both the “hero” and “adversaries” themes as the chaotic battle gets underway (CD 12, track 4, 1:32). Once again, it’s truly a let-down that we have such a congested sonic presentation here, since the brass and percussion give a real knockout performance here. Just when I thought that the struggle between the composer and his critics (we know that’s who he’s fighting since the music is lifted directly from the second movement) couldn’t get any more frenzied, the trombones enter with their beastly roars that cut right through the massive band (CD 12, track 4, 4:42-5:01). If we still had any inkling of doubt about the self-referential vanity of this symphonic poem, the composer quotes even more signature themes from his previous works in “Des Helden Friedenswerke” (“The Hero’s Works of Peace”), among them Guntram, Don Quixote, Don Juan, Death and Transfiguration, Macbeth, Also sprach Zarathustra and Till Eulenspiegel. Being a veteran Strauss interpreter, Karajan obviously knew all of these works intimately, perhaps by heart, and it shows in the conspicuous way in which he makes the orchestra recollect those quotations here. The final movement, “Des Helden Weltflucht und Vollendung” (“The Hero’s Retirement from this World and Completion”), as its title suggests, contains many episodes of slow, contemplative material, which the performers get through without letting the tension sag too much – it’s easy to see how this denouement could feel long-winded in lesser hands, but Karajan’s sight of the narrative arc and his ensemble’s beauty of tone makes this drawn-out, self-congratulatory epilogue more than just tolerable. A fine performance, then, though one that cannot stand up to its significantly better-sounding 1959 competitor, or indeed, adversary.

CD 12 ꞏ MONO: CONCERT NO. 14 ꞏ 25 February 1965 ꞏ Philharmonie, Berlin

CD 13 ꞏ MONO: CONCERT NO. 14 ꞏ 25 February 1965 ꞏ Philharmonie, Berlin

Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 8 in C minor (2nd version)

This performance of Bruckner’s Eighth is split across two discs, with the first and second movements featured on CD 12 and the 3rd and 4th on CD 13. A word about the edition used here: The hardcover book indicates that this is the “2nd version”, but that’s not entirely accurate; during my listening, it occurred to me that this is obviously the Haas edition of 1939, which combines both the first (1887) and second (1890) versions of the score. I’m unaware of any commercially available recording of this symphony by Karajan which uses any edition other than the Haas, which he also employed for his 1975 account with the Berliner Philharmoniker as part of his only completed Bruckner cycle, and for his 1988 take with the Wiener Philharmoniker.

The recorded sound here, like in the last two discs, leaves quite a lot to be desired, as the claustrophobic mono soundstage is the bane of every Bruckner tutti’s existence. Exhibit A here would be the first full statement of the first theme (CD 12, track 7, 0:58-1:22), where the ff across the orchestra sounds barely fuller than the Allegro moderato’s soft opening. I appreciate how nuanced Karajan here is in rendering the theme’s rhythmic complexity though, as he makes a pretty clear distinction between the triple-, double- and single-dotted rhythms in the brass phrase, a detail often obscured in other performances. The second theme is taken at a broadened tempo as it should be since it’s marked breit und ausdrucksvoll (broad and expressive) by Bruckner, and the articulation of its key element, the Bruckner rhythm (two quarter notes plus a quarter note triplet, five notes in total) seems to be meticulous as well, with legato (smooth) distinguished from tenuto (held) in the first violins (CD 12, track 7, 2:13-2:34). The third theme shifts back to a swifter tempo (CD 12, track 7, 4:05) even though the composer didn’t indicate any changes here, but this could be forgiven not because virtually all performances of this symphony have this in common, but because the lighter texture here, what with the pizzicato (plucked) strings, makes this shift feel natural. The buildup towards the codetta (CD 12, track 7, 5:07-5:15) is expertly done here, without the intensity accumulating too much too soon. The brass chorale in the development section is gorgeously blended and shaped, somehow realizing the composer’s rather counterintuitive demand for the brass to blare away at ff but also keep things sehr ausdrucksvoll (very expressive) (CD 12, track 7, 7:06-7:32). In the colossal recapitulation of the first theme, this recording thankfully is able to give us the fff that we need after all, though the upper brass sounds quite grating here (CD 12, track 7, 8:45-9:33). The coda has some wonderful moments, too, with it beginning suspensefully (CD 12, track 7, 13:52) and with the trumpets and horns bellowing out the first theme’s dotted rhythms in the wide-open tone that Karajan’s brass is renowned for (CD 12, track 7, 14:07-14:52). The Scherzo – Trio suffers sonically from the same lack of dynamic range as the previous movement; nowhere is that more apparent than during the fff tutti passage in the initial section (CD 12, track 8, 1:23-1:44) – it really doesn’t sound that much more powerful than the ff or even f that precede it, and judging from Karajan’s later recordings of the symphony, it’s clearly a reflection of this broadcast’s audio limitations, not of the maestro’s lack of formal mastery. The Adagio really impresses me with an aspect that I’ve observed in quite a few other recordings in this box set so far, namely that the double basses have been captured with a gentle but rich, booming quality. This makes the pizzicatos at the beginning of this slow, ethereal movement all the more exquisite. Unfortunately, things take a turn for the worse at the first of many passages featuring the movement’s celestial harp arpeggios, where the trumpets and first violins have an awfully strident tone (CD 13, track 9, 4:17-4:26). It’s a shame that this Adagio, so reliant on the beauty of string tone for which this orchestral partnership is highly regarded, is hindered by sonics that are so unforgiving of the upper end of the frequency range. Just as I feared, the towering climax towards the end of the movement (CD 13, track 9, 21:23-21:48) had me wincing as I once again reached for my trusty friend, the volume knob. I’m a big fan of the way Karajan began the finale here. Bruckner ordered a Feierlich, nicht schnell (solemnly, not fast) treatment, but sometimes we wouldn’t have known that given the severe urgency so many conductors begin this movement with. Among other details, a more moderate tempo allows the winds to enunciate the dotted rhythms that permeate the opening theme, and the timpani to execute its grace notes clearly, too. The trombones here are ferocious, which perhaps shouldn’t come as a surprise for those acquainted with Karajan’s other Bruckner Eighth recordings, but their refinement here is truly remarkable since it’s not just a matter of sheer volume but also of blend and transparency of tone (CD 13, track 10, 0:03-1:00). The second theme is off to a lovely start since the string choir is nicely cushioned by a generous amount of double bass (CD 13, track 10, 1:58-2:10), and the third theme building gradually towards the grand pause (CD 13, track 10, 4:27-5:15), which is observed for a good three seconds before the development section is allowed to arrive (CD 13, track 10, 5:18). The development section is notable for its forward momentum here, with Karajan maintaining continuity between each episode and masterfully navigating dynamic and articulation changes, such as in the transition to the march-like third theme where pp strings are suddenly interrupted by an ff orchestral tutti (CD 13, track 10, 6:11-6:16). The key for the interpreter here is to effectively realize Bruckner’s transitions, whether they be smooth modulations or simply fermatas, and still somehow weave a line through the overall form. I must say that Karajan never loses integrity throughout this movement, with his faithful adherence to the composer’s thoughtful indications being one of the primary reasons. The treatment of the recapitulation is another spot that shows Karajan’s structural grasp. The brass here return with an intensified version of the first theme, underpinned by thundering timpani and the woodwinds who are now also joining in with their grace notes (CD 13, track 10, 15:26). Comparing the first theme’s debut in the exposition with the recapitulation, it’s clear that the maestro had his band conserve energy for the latter, where the theme is extended to a higher register for the brass as well (CD 13, track 10, 15:52-16:38). The sense of arrival in the listener is that much more palpable because of that. The third theme in the recap has been brilliantly transformed into a quasi-codetta that foreshadows the impending coda with its mysterious harmonic turns, and despite Bruckner’s viel langsamer (much slower) marking, Karajan judges the tempo here wisely and never lets this build-up sag, fully appreciating the former march’s new transitional function (CD 13, track 10, 20:37-23:17). Our long-awaited coda is as gratifying as one would’ve expected, since it serves as the epiphany for this eighty-minute work. I especially like the way the proportion of the dotted rhythms echoes the pattern’s initial appearances from all the way back at the top of the symphony, as well as how the return of the scherzo’s main motif, now in the horns,are clearly audible among the balance (CD 13, track 10, 24:36-25:02). My only regret is that the final E-D-C descent that concludes the piece hasn’t really been given sufficient weight and time (CD 13, track 10, 25:43-25:45). This motif is a glorious transformation of the probing phrase from the symphony’s opening, thus the thematic idea of revelation could’ve been driven home more assuredly had Karajan observed the rit. and accent marks on these last three notes to a greater extent. Altogether, this is a formidable reading of a formidable symphony, and a testament to both the maestro’s affinity for this repertoire and to his orchestra’s mastery of it. I wish this live concert were presented in better sonics, so I’m all the more grateful that we have the marvellous DG studio accounts from the conductor.

CD 14 ꞏ MONO: CONCERT NO. 15 ꞏ 23 September 1965 ꞏ Philharmonie, Berlin

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Divertimento in B flat major, K. 287 “Lodron Serenade No. 2”

Richard Rodney Bennett: Aubade for Orchestra

Antonín Dvořák: Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Op. 95 “From the New World”

Compared to the 1987 version that Karajan and his orchestra recorded towards the end of the maestro’s life, the Divertimento here receives a swifter and leaner performance. Except for the Adagio, all of the movements here are quicker than the studio account made 22 years later. When checking the track list to compare timings, I noticed that a movement is missing from the current broadcast–instead of the second Menuetto, the fifth movement here is actually the Andante – Allegro molto, which is supposed to be the sixth and last movement of the piece. What gives? I wonder if the performers simply decided to omit the second minuet during the concert in order for the initial half of the concert to maintain a reasonable length, as the Divertimento is a 40-minute work when played in its entirety. Still, it would’ve been appreciated had there been an explanation in the hardcover notes – a notice that this disc only features “selections from the Divertimento in B flat major, K. 287 “Lodron Serenade No. 2” would be a needed courtesy for the listener, in my opinion. The performance itself is nice enough, though nothing worth writing home about. This is another case where the far better sonics of the later studio account makes it an easy recommendation over this radio broadcast, especially when we have no reason to believe that it is of a regular concert and not a historic event or special occasion.

The next piece is a treat for Karajan aficionados, as it’s never been recorded anywhere else by the conductor. According to Universal Edition, the work’s publisher, the composition was commissioned by BBC for the 1964 Proms, making it barely a year old at the time of its performance here by the Berliners. One can’t help but wonder why the maestro chose to program the work. If anything, the performance here, along with the Capriccio for Soprano, Violin and Orchestra from CD 7 and Atmosphères from CD 22, go to show that Karajan had also done work to promote contemporary music, contrary to the misconception that the maestro was really only interested in the Austro-Germanic classics and some Romantic repertoire here and there. It’s an atmospheric morning song (as its title suggests) ripe with glowing but at times mysterious timbres – this, along with its instrumentation of strings, percussion and celesta (among others) evoke the mood of the night music in Bartok’s Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta.

The second half of this concert consists of a Karajan favourite. The maestro has an exceptional reputation for his performances of this Czech-American symphony, one of the most celebrated works of the 20th century. Notably, his 1985 recording of the “From the New World” symphony with the Wiener Philharmoniker is widely lauded as one of the finest ever made of the piece, and even in 1964, which is just a year before the current concert, he had recorded a highly acclaimed account with the Berliner Philharmoniker as well. It should come as no surprise to the reader by now what I’m about to comment regarding the sonics of this radio broadcast: it’s definitely good for its age, but in no way comparable to these performers’ stereo accounts. This live concert is brisker than either of its siblings, with plenty of energy in the fast movements that keeps propelling forward. It always strikes me how in his performances of this piece, the current one included, Karajan doesn’t start the first theme of the opening movement very quickly (CD 14, track 7, 1:54) , even though it represents a shift to Allegro molto (very lively) from the introduction’s Adagio (slow). Presumably, this is to allow the dance-like second theme (CD 14, track 7, 3:00) and lyrical third theme (CD 14, track 7, 4:02) some much-needed head room to be more relaxed, as Dvořák technically asked for the whole movement, except for its introduction, to be played in the same lively tempo. The coda is as fiery as it should be, and it’s notable that even here the composer doesn’t request an intensified speed (CD 14, track 7, 8:21). Karajan respects the composer’s wish in that regard, though it’s even more obvious now that by comparison, the third theme which precedes the coda is taken at a much more leisurely rate than the other sections. The “landmark” of the symphony, its poignant melody in the Largo (very slow, broad), is played enchantingly here, with a spot-on balance between the lone English horn and the strings, then later clarinets and bassoon as well, even as the dynamics between the two groups change from p against pp to pp against ppp. It is simply gorgeous (CD 14, track 8, 0:42-2:02)! Our Scherzo is really molto vivace here indeed, taking just over eight minutes. The ensemble balances in the scherzo section are fantastic, with the contrapuntal writing coming through loud and clear, while the tutti are precise and powerful (CD 14, track 9, 0:00-0:44). Like in the first movement, Karajan relaxes the tempo in the lyrical second theme here, and even though this isn’t necessarily authorized by Dvořák per se, it’s a thoughtful touch (CD 14, track 9, 1:30). The finale is another certified Karajan moment: In all recordings of this symphony that the maestro ever made, he had always asked the trumpets to be the hervortretend (striking, prominent, salient) force in the main theme here (CD 14, track 9, 0:15-0:40). Listen especially to the second phrase when Trumpet I doubles the tune at an octave higher – what a magnificent tone (CD 14, track 9, 0:27-0:40)! It baffles me how many conductors don’t allow the trumpets to take centre stage here. From other video recordings that the maestro made, it’s almost certain that the trumpets are also doubled here, with two to each part rather than one. The latter half of the first theme is done at a breathtaking speed, with the band never losing control despite its huge impetus (CD 14, track 9, 1:08-1:35). I’m glad that the climax of the graceful second theme is judged properly at the opening Allegro con fuoco (lively with passion) tempo (CD 14, track 9, 2:30) that governs the whole movement, an arrangement Dvořák used throughout the symphony. The coda is absolutely riveting (CD 14, track 9, 8:02-10:34), not just in terms of pure speed, but also the intensity of sound that the Berliners are capable of, especially in the climatic first half of the section (CD 14, track 9, 8:02-8:52). If there’s one spot in the whole concert that I wish it had been captured in stereo sound, this would certainly be it. The jazzy sixth chord in the closing bars is given the proper dance-like bounce, too (CD 14, track 9, 10:09-10:14). To put the cherry on top, the final chord in the winds is sustained for a good 8 seconds, as lunga corona (long-held) as the composer asked for, with the sonority coming down to a true ppp before fading away (CD 14, track 9, 10:20-10:28). This is an exceptionally powerful and stylish performance, and one could easily understand why Karajan was so admired for his command of this great symphony.

CD 15 ꞏ MONO: CONCERT NO. 16 ꞏ 30 December 1965 ꞏ Philharmonie, Berlin

Richard Strauss: Also sprach Zarathustra, Op. 30, Don Quixote, Fantastic Variations on a Theme of Knightly Character, Op. 35, Pierre Fournier, cello, Giusto Cappone, viola

We’re now at another all-Strauss concert, starting off with perhaps the Karajan piece, no less. The maestro has three spectacular studio recordings of Also sprach Zarathustra to his name, with two of them having achieved legendary status: the 1959 rendition with the Wiener Philharmoniker, which was utilized by Stanley Kubrick in 2001: A Space Odyssey; and the 1973 account, which is widely recognized as one of the greatest orchestral recordings ever made. This broadcast, although recorded live and as such didn’t have the luxury of being edited and engineered to the nines, had huge shoes to fill indeed. Sonically, it should be no surprise that it doesn’t begin to compare to the aforementioned trio, with the massive orchestral sonority degenerating into almost pure noise in the Sonnenaufgang (sunrise) opening (CD 15, track 1, 1:21-1:35). The usually rich Berliner Philharmoniker strings also sound wiry in the lyrical sections, such as the main theme of the Von den Hinterweltlern (Of the Backworldsmen) (CD 15, track 2, 0:56). The soaring theme in Von den Freuden und Leidenschaften” (Of Joys and Passions) has the strings and horns desperately crying out for more dynamic range and presence (CD 15, track 3, 0:39-1:42), too, but alas, there’s only so much mono sound could do for Strauss’ lush, Late Romantic orchestration. Due to the presence of so many other fantastic recordings of this piece, which could easily start and end with Karajan himself, I cannot recommend this performance, regrettably.

The Don Quixote, being the second half of the same concert, is captured in similarly inadequate audio. The solo cello that flows through Variation I: Gemächlich. “Abenteuer an den Windmühlen” (“Adventure at the Windmills”), for instance, at times struggles to be heard over the rest of the ensemble, being deeply recessed into the background (CD 15, track 13, 0:35-0:50). Things certainly don’t improve in the raucously scored Variation II: Kriegerisch. “Der siegreiche Kampf gegen das Heer des großen Kaisers Alifanfaron” (“The victorious struggle against the army of the great emperor Alifanfaron”), what with its bleating sheep mimicry and all. One has to sample only a few seconds of the conductor and his band’s studio recording on DG, made only a year after this broadcast in 1966, to realize just how much sonic information we’re missing out in this mono version. What a disappointment it is, that these otherwise fine accounts of two great Strauss symphonic poems have been let down this way. Unfortunately, at first it seems that we’ll have to wait “two more years”, that is, until the 1967 recordings of this box set for more direly needed stereo sound. Fortunately, a quick consultation with the hardcover notes identifies the first instalment of that as none other than our next disc.

CD 16 ꞏ STEREO: CONCERT NO. 17 ꞏ 22 October 1967 ꞏ Philharmonie, Berlin

CD 17 ꞏ STEREO: CONCERT NO. 17 ꞏ 22 October 1967 ꞏ Philharmonie, Berlin

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Concerto for 3 Pianos and Orchestra in F major, K. 242, Jörg Demus, Christoph Eschenbach, Herbert von Karajan, piano

Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 4 in E flat major “Romantic” (2nd version)

Besides having been captured in stereo sound, this broadcast is remarkable in that it’s the only known recording where Karajan plays the piano in a Mozart concerto. To be precise, he plays one of three piano parts in this Mozart concerto, as the piece is written for three pianos. The maestro finds himself in formidable company here, with Demus and Eschenbach, both pianists with eminent Mozart reputations, taking on the other parts. There’s a curious oversight in the hardcover book notes here, as they fail to mention which musician played which solo part – though given the convention of listing the parts from primo to secundo and so on, it’s pretty safe to say that Karajan was responsible for tertio, or Piano III here. Our trio does a wonderful job in matching their tone, articulation and phrasing throughout the work, so that there’s a uniformity in the piano contributions. I’m grateful that we finally have stereo sound here, as the two channels allow the mix of the three pianos to be spread across nicely across the soundstage so that there isn’t a sense of congestion that could sometimes be an issue in concertos with more than one solo part. When all of them are playing, such as near the ending of the piece, it’s still relatively easy to tell the trio of pianos apart (CD 16, track 3, 5:04-5:14).

The second half of the concert is on its own disc, given the length of the work. As with the previous Bruckner Eighth, the notes in the book really should’ve specified that the edition played here is the Haas one, in this case published in 1936 using material from 1878/1880, because there are multiple editions of the 2nd version, including the 1878, 1881 and 1886 variants. Notably, Karajan had made all of his recordings of this symphony throughout his career using the Haas edition. Starting off with the recorded sound, our broadcast here is substantially better than the mono ones heard in this box set so far indeed. The stereo imaging is much wider, providing a realistic perspective of the massive sonority that the Berliner Philharmoniker was (and is still) famed for, especially in Late Romantic repertoire like this. Compared to Karajan and the BP’s Bruckner Fourth studio recording for EMI three years later, this broadcast has the brass more forward and present, a feature immediately apparent when the trombones make their initial entrance with the “Bruckner rhythm” at the first theme of the Bewegt, nicht zu schnell (Quick, not too fast). This actually startled me with their impressive wall of sound (CD 17, track 1, 1:48). I appreciate how the tempo for the second theme here is kept on par with that of the first theme; Bruckner never asked for a different speed here, with etwas gemächlich (somewhat leisurely) being the only indication in some editions, but here in the Haas, not even that is given, contrary to some conductors’ intuition to relax the pace for a more bucolic feeling (CD 17, track 1, 2:37). As a departure from the 1970 EMI account mentioned above, here the brass chorale in the development section, which is based on the horn call of the first theme, is reinforced by timpani rolls (CD 17, track 1, 9:49-10:42). Since the Haas score doesn’t call for this addition, it’s safe to assume that the conductor decided to put them in for dramatic effect in this live performance. The dynamic range of Karajan and his ensemble are put on outstanding display with the stereo sound that we have, and I find myself enjoying this live performance a great deal more than the EMI studio account due to this advantage. The coda is built in a truly gradual manner here, with the tempo kept steady from the start (CD 17, track 1, 16:34), and the intensity slowly ramping up over the course of two minutes. My only reservation is that when the horn calls return near the end, they’re somehow drowned out by the timpani rolls and the dotted rhythms in the rest of the winds (CD 17, track 1, 18:07). Fortunately, they do eventually get the spotlight that they deserve in the closing bars. Overall, this is an exciting and propulsive reading of the opening movement, one that is almost a full two minutes quicker than this group’s later EMI studio effort. In the second movement, the wide dynamic range of this broadcast becomes challenging, with quiet sections in the strings, such as the pizzicato version of the A theme (this movement is in five-part ternary form, A-B-A-B-A-Coda) being so faint as to be virtually inaudible unless my volume knob lent a helping hand (CD 17, track 2, 3:10). In the EMI 1970 recording, the strings have a higher volume floor even in the softest dynamics that keep them nice and plush, but not so here. The articulations in the “hunting scherzo” are impeccably rendered. No matter how softly or loudly, it seems like the Berliner winds could always keep up with the crispness and lightness of their staccatos throughout the main sections of this third movement, and that is apparent from the beginning with the four horns. I appreciate how a combination of Karajan’s interpretation and the audio engineers’ decision allowed trumpets and horns to be clearly differentiated here, with trumpets taking the foreground and the horns chirping in the back (CD 17, track 3, 0:01-0:23). The maestro is renowned for his Bruckner performances for many great reasons – to me one of the main ones is surely his sense of structure, and the finale is a wonderful showcase of that important attribute of his. Listen to how he expertly builds the enormous opening paragraph, always accumulating tension and sustaining the melodic line until a cadence is finally reached (CD 17, track 4, 0:00-3:00). The musicians deserve tremendous credit for their handling of the third theme as well, where the staccato motif from the previous movement returns (CD 17, track 4, 5:45). The articulations are appropriately marcato sempre (always marked) like Bruckner demands, and Karajan ensures that the rhythmic incisiveness and ff dynamics don’t cause himself and his colleagues to lose grip of the tempo either. The recapitulation (CD 17, track 4, 11:07) and following coda (CD 17, track 4, 17:47) consists of some of the most powerful playing I’ve heard in this entire box set so far, with the ensemble’s polish being truly remarkable. We mustn’t forget that this performance is unedited in the sense that no patching or retakes have been done. The brass’ blend, the strings’ richness, the timpani’s ferocity…everything comes together like it had been a laborious studio production, but with the extra nervous energy exclusive to live performances. What an exceptional testament to the Brucknerian accolades that this conductor and orchestra well-deservedly enjoyed, this concert is.

CD 18 ꞏ STEREO: CONCERT NO. 18 ꞏ 1 January 1968 ꞏ Philharmonie, Berlin

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125, Gundula Janowitz, soprano, Christa Ludwig, mezzo-soprano, Jess Thomas, tenor, Walter Berry, bass, Chor der Deutschen Oper Berlin, Walter Hagen-Groll, chorus master

We’re now at the third and last Beethoven Ninth of the box set, this being the most abundantly featured piece in this release. The present broadcast will be compared with the earlier one on CD 10 as it’s also in stereo sound, and references to Karajan’s 1963 studio classic will also be made as it’s for many the Beethoven Ninth, bar none.