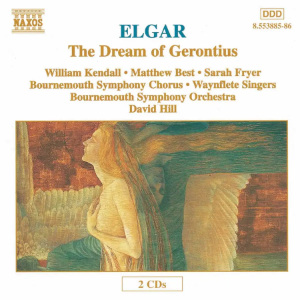

Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934)

The Dream of Gerontius, Op 38 (1900)

Gerontius – William Kendall (tenor); The Angel – Sarah Fryer (mezzo-soprano); The Priest / The Angel of the Agony – Matthew Best (bass-baritone)

Bournemouth Symphony Chorus; Waynflete Singers

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra/David Hill

rec. 1996, Wessex Hall, Poole Arts Centre, Poole, UK

Text included

Naxos 8.553885-6 [2 CDs: 94]

Just recently, I updated my survey of recordings of The Dream of Gerontius. That undertaking reminded me that the recording conducted by David Hill was, to the best of my knowledge, the only one that I’ve never heard. Furthermore, and equally unaccountably, it seems we have never reviewed it on MusicWeb. I thought it was high time that both of those omissions were rectified, particularly since this version is still available, so I got hold of a copy.

It may be worth beginning by saying something about the soloists since some of their names may be unfamiliar. The late William Kendall (1951-2024) was a tenor Lay Clerk at Winchester Cathedral for a long period (1975-2021). I learned from the booklet that he was a pupil of both Robert Tear and Sir Peter Pears. I believe he was a frequent collaborator with Sir John Eliot Gardiner and the Monteverdi Choir; I remember him principally as the excellent tenor soloist on Gardiner’s first (1989) recording of Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis. I’d not previously encountered the British mezzo, Sarah Fryer but her short biography in the booklet details a wide-ranging CV. I looked her up online and the Operabase website mentions that in 1997/8, not long after the present recording was made, she sang at Bayreuth, taking the roles of Wellgunde in both Das Rheingold and Götterdämmerung (for James Levine), as well as First Squire in Parsifal (for Giuseppe Sinopoli). Probably the most familiar name on the soloist roster is Matthew Best, who is not only well-known for his operatic and concert career as a singer but also as the founder-conductor of The Corydon Singers.

This recording was made during the period (1987-2002) when David Hill was Master of Music at Winchester Cathedral. So, it’s no surprise there was a definite Wessex element to the project with the orchestra and main chorus from Bournemouth and the involvement also of the Waynflete Singers, who are Wiunchester-based, I believe. Hill was their conductor in those days; I wonder if they sang as the semi-chorus. Incidentally, I noticed that at the time of this recording the Chorus Master of the Bournemouth Symphony Chorus was Neville Creed; he’s about to retire at the end of the 2024/25 season after 30 years running the London Philharmonic Choir. Since he and David Hill were the conductors responsible for preparing the two choirs involved in this recording it’s no wonder that the standard of choral singing is impressive.

Throughout this performance the combined chorus sings very well and I noted their excellent attention to detail in terms of such matters as dynamics. On one or two other recordings that I’ve heard, the chorus has even greater impact but I think that’s due to the engineering; here, the choir is heard realistically balanced, as would be the case in the concert hall, behind the orchestra. I hasten to say, though, that this balance doesn’t blunt their singing; there’s ample heft and presence at such places as ‘Praise to the Holiest’ and in the Demons’ Chorus. In that latter chorus I liked the deliberately nasty tone with which the singers deliver lines such as ‘To psalm droners’; a minute or two later, they positively sneer when they sing ‘Ha! ha!’ ‘Praise to the Holiest’ comes off well; the very opening of that chorus has plenty of impact – as does the reprise. After that reprise Hill doesn’t press the tempo excessively, which means that the double chorus writing has clarity; it also means that he has something left in reserve when Elgar instructs the conductor to whip up the tempo significantly. My one slight disappointment comes in the Angelicals passage which precedes ‘Praise to the Holiest’. The ladies of the chorus sing it nicely but I don’t feel that Hill gets them to invest the rhythms with quite the spring that I’ve heard on several other versions, including those conducted by Nicholas Collon, Sir Mark Elder and Paul McCreesh. All the contributions from the semi-chorus are excellent.

Inevitably, in a work such as this the focus is primarily on the singers. However, I should make it clear that the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra is consistently impressive. The Prelude to Part I is a conspicuous success for two reasons. One is that David Hill demonstrates a fine sense of Elgar style; the second is the quality of the playing, which is very refined yet has power and sonority when required. I greatly admired the tender, diaphanous playing of the strings in the short Prelude to Part II; hereabouts, they really establish an other-worldly ambience. Those are the places where the orchestra is in the spotlight but elsewhere, the BSO also offers distinguished playing.

Turning to the soloists, it makes sense to consider Matthew Best first because he has the least to do and one mustn’t fall into the trap of overlooking his contribution. As I’ve remarked in some other reviews of this work, the bass or baritone who sings in Gerontius has a tricky assignment because the roles of the Priest and the Angel of the Agony ideally call for different types of voice. The former has a higher-lying tessitura while the latter is a more commanding role for a basso cantante. My experience on disc is that the majority of singers tend to be better suited to one role than the other; notable exceptions, who have excelled in both roles, have been John Shirley-Quirk and, especially, Robert Lloyd, who sang on Sir Adrian Boult’s 1975 recording. I think Best joins that select group. He’s a magisterial Priest and then sings the role of the Angel of the Agony with commanding presence.

To the best of my knowledge, I’d not previously heard Sarah Fryer. There’s much to appreciate in her singing. I especially liked the touching simplicity with which she delivers the Farewell; here, her comparative restraint is moving. At all times she produces a sound which is clear and true; her diction is excellent. There are times, though, when I wished she’d sung with greater expression. For instance, in ‘A presage falls upon thee’ her careful adherence to the dynamic markings makes her delivery expressive but I miss the warmth that some of her rivals on disc have brought to this passage. I enjoyed her performance but in the last analysis I feel that for all its virtues her portrayal of the Angel isn’t sufficient to move me.

William Kendall does very well as Gerontius. I feel that his interpretation, while not lacking power where needed, tends more towards the lyrical side of the role – not that there’s anything wrong with that. Right at the start he makes a positive impression when we experience for the first time – but emphatically not the last – his clear tone and excellent delivery of the words. His voice is lighter than some I’ve heard in the role but it lacks nothing in firmness. One detail I noticed was that on a few occasions where both a high and a low alternative are marked in the part, Kendall opts for the lower one. This is clearly nothing to do with tessitura – the top B flat rings out with anguished clarity at ‘In Thine own agony’ – but, rather, I think that Kendall has observed that in the Novello vocal score the lower alternatives are in large print and the high alternatives are in small print. In ‘Take me away’ he sings the lower notes at ‘and go above’; the only other tenor I’ve ever heard do this is Peter Pears on the Britten recording. But Kendall goes further than Pears; in ‘Sanctus, fortis’ he takes the low alternative at ‘Adoration aye be given’ (just before Cue 52) and, shortly thereafter, similarly sings the low notes at ‘mortis in discrimine’; I’ve never heard either of those alternatives before. I mention all this partly because it may momentarily disconcert some listeners but also – and more importantly – because it demonstrates, I think, the attention to detail in Kendall’s performance of the role. There’s nothing studied or pedantic about his singing but time and again I noticed how scrupulous he is, especially with the dynamics. Just one example will suffice: in Part II (just after Cue 17) in the passage beginning at ‘I will address him’ he carefully observes the dynamic gradations and the result is excellent.

There are occasions when I wanted more from him. Just before the Demons’ Chorus there’s no real sense of fear at ‘But hark! Upon my sense comes a fierce hubbub’ and I miss the awe that a singer such as Nicky Spence brings to ‘I go before my judge’. On the other hand, Kendall makes a very good impression in ‘Sanctus, fortis’ and ‘Take me away’ opens, as it should, with a cry of anguished ecstasy. Where I think Kendall is at his most persuasive is in the opening minutes of Part II, before and during Gerontius’s first encounter with the Angel. Here, his light, refined and free singing, supported by David Hill’s understanding conducting, creates a sense of lightness and other-worldliness. Some other tenors on disc have brought even more to the role of Gerontius in terms of variety of expression – Nicky Spence immediately comes to mind, as does the incomparable Heddle Nash – but there’s much to admire in William Kendall’s performance; I think he brings great understanding and no little sensitivity to the role.

I’ve alluded once or twice already to David Hill’s conducting. He has the measure of the score and gets the best out of all the musicians, both singers and players. I think his direction of the score is both idiomatic and convincing. He pulls off all the big dramatic moments and, in addition, he’s absolutely at one with his soloists, especially in the intimate passages of Part II.

The sound is good and the booklet includes a useful note by Andrew Walton and the full text of the oratorio.

It has taken me far too long to catch up with this recording but I’m very glad that I have done so at last. Had I reviewed it when it was first issued, I’m sure I would have described it as a fine bargain but the price of Naxos discs has risen quite a lot since then and the label is no longer in the bargain category. Irrespective of price, this version has much to commend it. For all its merits, though, it doesn’t displace my existing recommendations, which are (in alphabetical order) the recordings conducted by Barbirolli, Sir Andrew Davis, Elder and McCreesh.

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free