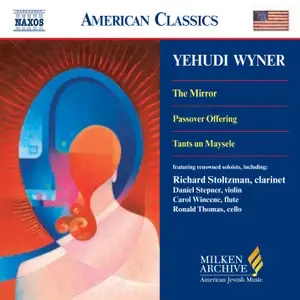

Yehudi Wyner (b. 1929)

The Mirror (1972/73)

Passover Offering, (1959)

Tants un Maysele, (1981)

rec. 1992/99, Mechanics Hall, Worcester, USA; Slosberg Recital Hall/Brandeis University, Waltham, USA

Naxos 8.559423 [58]

Three pieces by Yehudi Wyner – The Mirror, Passover Offering, and Tants un Maysele – are presented here in world-premiere recordings. Wyner, son of Lazar Weiner, “the acknowledged avatar of the Yiddish art song medium,” embraces in this music different aspects of Jewishness, from traditional mentalities and folk music to 20th century literature. He approaches the music always from “contemporary aesthetic and technical thought,” meaning that though many of the themes are traditional, and much of the music is rooted in klezmer bands and folk song, all of the ideas on this recording are engaged with from modernity’s perspective, regarding old themes of tradition from the vantage point of the twentieth century.

The Mirror (1972-73) is a “suite from the incidental music for the play by Isaac Bashevis Singer”. The play tells the story of Zirel, a young Jewish woman in an Eastern-European shtetl (a religiously-oriented market town), who, after staring at herself naked in a mirror, is seduced by a demon. Its main themes are sexual frustration caused by religious and social views, and the dangers of the temptations and fantasies that can be spawned from those frustrations. Sarah Blacher Cohen, scholar of Jewish-American fiction, described the demon as “‘Puckish”. Wyner’s music can be similarly described: mischief, humour, parody, and rebellion are the tools used to convey Zirel’s sexual confinements and struggles. “And just as Singer used parody and distortion,” writes Wyner, “to reveal a contemporary point of view about conventional practices and modes of thought, so I utilised musical parody and stylistic distortion to achieve a similar result.”

The k’tuba is a Jewish marriage contract, and, of the suite’s fourth movement, “Reading The K’tuba,” Wyner said that “the banality of this k’tuba music is intentionally ironic: the ceremony is a ‘black wedding’ – as if a wedding in hell.” By emphasising that banality, Wyner undermines the importance of the marriage, making it almost sarcastic in tone, a sham. Wyner, like Singer, uses irony and black humour to cast a modern eye back on old traditions, revealing them to be shallow and inauthentic, cloaks over the true desires of the people practising them. In the light of hindsight, these practices are seen as fetters that tie their people to tradition, restricting their lives, leaving them little choice but to daydream of stepping outside of what their communities call acceptable, to explore themselves and their desires, and increasing the temptation to indulge these fantasies. Traditions and temptations such as these are the core themes of Singer’s play, and through ingenious use of irony, Wyner reveals the traditions’ flimsiness and the inevitability of the temptations they create. For restrictions give the restricted power, the power of curiousness, which has led astray many a “faithful but bored shtetl woman,” as Blacher Cohen described the protagonist of the short story on which Singer inspired his play.

Wyner also wrote of The Mirror that “The overall style, however, maintains a basic conventional attitude, allowing departures from the conventions to speak more forcefully.” Rebellion is not only one of Wyner’s primary tools, but also an underlying theme of the play, as Zirel’s alliance with the demon can be seen as a revolt against Jewish tradition. To rebel, as Wyner explains, there must first be conventions: “For the music, I drew upon my longtime exposure to the various musics of Jewish tradition – from secular folk and religious song to the music of klezmer bands; from the monophonic modes of the Near East to the music of the Sephardi Jews of the Mediterranean basin.” These traditions provide the patterns against which Wyner’s compositions rebel. He has an ear for dissonance, a knack for unease, that jars the listener against the modes of tradition: on “Incantation,” the clarinet grates against the violin and double bass; on “Invocation Of The Jew Of Babylon,” the clarinet provides a long, drawn out trill beneath the rough-edged violin lines. New York Times critic, Peter G. Davies, wrote that “Mr. Wyner’s music, although reflecting Jewish subject matter, is of a highly dissonant idiom”. Wyner understands that there is no dissonance without harmony, no rebellion without conformity, and rather than dismiss tradition as antithetical to modernity, he places modern compositional techniques within traditional structures, revealing through contrast how delicate tradition is, and how shocking and frightening deviation from it can be. There is, though, no growth without deviation from the norm. It is therefore tempting to describe Wyner’s music here as expansions of tradition brought about through defiance, rather than outright and angsty rebellions against it. While he does rebel, he does so to highlight the dangers of blind conformity, complimenting the themes of Singer’s play, and not for antagonism’s sake.

Throughout, the players perform with a deftness and lightness of touch that mirrors the intentions of Wyner and Singer. Clarinetist, Richard Stoltzman, in particular, helps set the tone by leaning into the predominant emotion of each movement and bringing them out through playing the role each assigns. In “Home Variations,” for example, his tone is full, low, and yearning, echoing the lamenting of Daniel Stepner’s violin. On opening track, “Demon’s Welcome,” however, percussionist Robert Schulz leads in the demon with violent, aggressive playing on bass drum, snare, and cymbal, symbolising the threat the demon poses to Zirel.

Passover Offering (1959) exhibits different moods as they appear in the story of Passover. “I sought,” says Wyner, “to evoke the drama and sentiment of some aspects of this legendary history.” To create these “reflections and meditations on certain situations,” he chose instruments – flute, clarinet, trombone, and cello – which would act as “metaphors” for biblical instruments. The trombone stands in for the shofar, for example, “because it seemed to me the most primitive of the modern brass instruments in the sense that it is valveless.”

Each of the five movements evokes the emotions of an episode in the Passover story. Movement one, “Lento,” with its heavy trombone line saddled atop a plucked cello, seeks to conjure images of oppression and slavery. Movement two, however, titled “Energico,” is Wyner attempting to capture the Jews’ fight against their oppressors and eventual escape by sea, leaving the Egyptian army to be swallowed by its waters. “Grave,” the fourth movement, was made as a reflection of “a kind of lamentation and uncertainty – a kind of canzona.” Its mournful trombone playing and pining flute create a sense of sadness and fearfulness, and make it an obvious highlight.

Trombonist, David Taylor, is the standout performer here. Whether he is weighing down “Lento,” with its theme of oppression, or ushering in the battle of “Energico” with his military-charge of an introduction, he fits Wyner’s artistic intentions perfectly, bringing forth the essence of each movement by adjusting his tone to fit the prevailing evocation.

The final piece, Tants un Maysele (1981), is made of two movements, commissioned by the Aeolian Chamber Players, who wanted a particularly Jewish-flavoured piece. Wyner took his title from a pair of piano pieces his father dedicated to him when he was a young child, and Wyner used this commission as a chance to repay his father for that childhood dedication. “So,” Wyner says, “I began working on a piece that would be dancelike, filled with Hassidic-type dance rhythms, but also infused with a kind of violence and peremptory rage that one would not find normally in a Hassidic dance; and, also, with a sense of extreme mystery and confusion.” Indeed, the wildness of “Tants” (which means “dance”) gives way to an amorphous, mysterious close, while “Maysele” (“little story”), begins with a quiet theme – “a kind of polka-mazurka,” as Wyner puts it – that is transformed throughout the piece from something “realistic,” i.e. recognisably Jewish, into “surreal or abstract shapes – some of which remain substantial, while others evaporate in a haze of mysticism or nostalgic speculation.”

It is Wyner himself who stands out the most here. His piano playing is hard, almost aggressive, and passionate on “Tants” where he pulses and throbs beneath Bruce Creditor’s menacing clarinet, On “Maysele,” though, he caresses his lines out of the keyboard at the intro, before growing firmer as the piece progresses, luring the listener in through his shifts in emotional tone.

Throughout the CD, the sound is crisp and pure, but it never loses a menacing edge, which colours The Mirror in particular with a sense of evil fitting its demonic character and themes. The CD’s booklet is extremely informative, and it is from there that all the quotes given in this review are taken.

Much of the material presented herein deconstructs Jewish music through modern compositional techniques and perspectives. Wyner, by juxtaposing traditional elements of Jewish music with dissonance, and by considering them from his place in the modern age, makes these old musics come alive. Without blindly rebelling, he defies the settings of tradition, putting it in a new, contemporary context, allowing for it to be viewed afresh and seen as a vital pool from which to draw inspiration. His music is a new take on old themes, the themes that have helped build the culture that shaped him, and he has here added to that traditional body of work in an inventive, exploratory, and meaningful fashion.

James Fleming

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free

Performers

The Mirror:

Richard Stoltzman (clarinet); Daniel Stepner (violin); Robert Schulz (percussion); James Guttman (double bass); Carol Meyer (soprano); Judi Brown Kirchner (mezzo-soprano); Matthew Kirchner (tenor); Ricard Lalli (baritone); Yehudi Wyner (speaker)

Passover Offering:

Richard Stoltzman (clarinet); Carol Wincenc (flute); Ronald Thomas (cello); David Taylor (trombone)

Tants un Maysele:

Daniel Stepner (violin); Bruce Creditor (clarinet); Jennifer Langham (cello); Yehudi Wyner (piano)