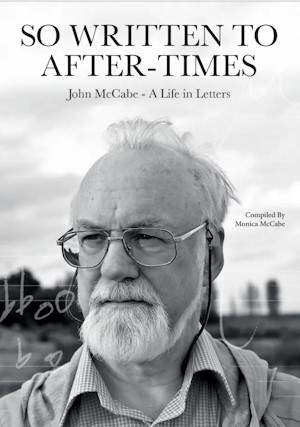

So Written to After-Times

John McCabe – A Life in Letters

Compiled by Monica McCabe

Published 2024

Paperback, 260 pages

ISBN 978-0-9514795-6-8

Forsyth Brothers Limited

John McCabe (1939-2015) was a major British composer and a distinguished concert pianist. He wrote ballets, symphonies, film scores, concertante works, as well as piano and chamber music. He was well established by the 1970s. Notturni ed Alba for soprano and orchestra (1970) and The Chagall Windows for orchestra (1974) were among the most successful of his pieces performed and recorded. There is in this book a letter to McCabe from a more senior composer, William Alwyn, who told him he found The Chagall Windows “a magnificent symphonic work – wholly satisfying shape and masterly in execution, with passages of great beauty”.

Clearly, such a figure needs good publicly available commentary and documentation, so that current and future generations can discover, or even rediscover, his music. McCabe has not fared too badly in that regard. There were articles in learned journals, and a 1991 volume by S. R. Craggs entitled John McCabe: A Bio-Bibliography. George Odam, frequently encountered in this book as a correspondent, edited Landscapes of the Mind: The Music of John McCabe, published in 2008 by the Guildhall School of Music and Drama.

This is a different kind of publication, and just as valuable. So Written to After-Times (John Milton’s words) has the subtitle “John McCabe – A Life in Letters”. Monica McCabe has selected 315 letters, postcards and emails from the composer’s archive. The first letter, from organist Frederick Wood, advised the eight-year-old boy that a march or dance for piano might be easier to write than a symphony. He cannot have known then that young McCabe would write thirteen symphonies by age 11, all of course later suppressed.

The last item in the book is a sample email sent by Monica McCabe to inform people of her husband’s passing around midnight on 13th/14th February 2015. She appends to that email text, as so often in the volume, additional details of interest: the contents of the CD of music to be used at his funeral, and a commentary on the selection. One learns, for instance, that the Fuga Duodecima from Hindemith’s solo piano work Ludus Tonalis is included because John McCabe felt it “was the most beautiful fugue ever written”.

That sent me to the CD shelves to take down McCabe’s 1995 recording of Hindemith’s work for Hyperion. It was also a reminder of his range as a pianist. He recorded all the Haydn sonatas, when few if any were played by other artists, in a major piece of musical resurrection. He also performed a lot of contemporary, especially British, music for piano. Near to the Haydn and Hindemith in my collection is McCabe’s Hyperion disc of Howells’s piano music. Many of his fellow British composers were grateful for his advocacy of their pieces, and say so in this correspondence; that includes William Alwyn, Richard Rodney Bennett, Alun Hoddinot, John Joubert, William Mathias, Nicholas Maw and Judith Weir, among others. Not only the British are found here: André Previn is also a grateful beneficiary of McCabe’s playing.

There is even a solitary letter from Britten in 1967, responding to McCabe’s struggles with Britten’s piano solo Notturno. As Monica McCabe again helpfully explains, McCabe’s hands had a narrow spread. Britten suggests that “the two chords you find unplayable should be very quickly spread […] much preferable to a very deliberate spread”.

Another pianist’s technical issue arises when McCabe observes he knows “at least one pianist who has given up playing [Ravel’s] Alborada del Gracioso, as the [fast] repeated notes are so unreliable on a Steinway […] but a Bösendorfer would be much easier, I suspect.” McCabe, Monica McCabe tells us, preferred a Bösendorfer, “unless he could get a good Fazioli”. A Fazioli even gets a credit on the aforementioned Hindemith recording.

There are numerous plums of this kind, but we also get a great amount of valuable information about what matters most: McCabe’s compositions. In the 1970s, McCabe took to writing for the stage with a two-act ballet Mary, Queen of Scots. It was not the last such work. Stuttgart Ballet asked him to write a ballet, a sign of his later international reputation. He wrote for them Edward II, to a scenario from Marlowe’s play, premiered in 1995 with choreography by David Bintley. This is richly documented in the book with correspondence between composer and choreographer. McCabe worked with Bintley again on his pair of Arthurian ballets for Birmingham Royal Ballet, Arthur Pendragon (1999) and Mort d’Arthur (2001).

McCabe received many commissions. The London Philharmonic Orchestra commissioned his Symphony on a Pavane (Symphony No. 6), first performed in 2006. His first and only Proms commission was a 2013 short curtain-raiser Joybox, his last orchestral work. Both these works get detailed appreciative remarks from several correspondents in the book.

Some non-musical asides tell us other interesting things about McCabe, such as his reading. For example, he mused upon an Austen-themed recital to be given in a House in Kent the novelist often visited. That, we are told, led him to read a Jane Austen biography. He announced he would next read all her work again, “when I have finished Proust, if I ever do”. As one reads the book, one gets to like its subject more and more. I recall that my friend the composer Christopher Headington told me how much he liked the man and the music. Now I see why. McCabe must have had much energy – I have not yet mentioned his academic work, leading institutions and writing short studies of Bartók, Rachmaninov and Haydn, and a major study of Alan Rawsthorne.

The book is very well illustrated. The paperback is strong and the right size, on high-quality paper and printed to fit its purpose. There is a page index of correspondents, but no other indices. An index of the music mentioned would have made a valuable addition. Many readers would turn back to it for information on particular works, which could often be observations not found anywhere else, such is the richness and detail of the contents. But there are often economic constraints that hinder these things. And this is still a fine addition not just to our knowledge of John McCabe, but to the spirit and culture of his profession, in his own time and place.

Roy Westbrook

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free

Previous review: John France (December 2024)