Déjà Review: this review was first published in March 2007 and the recording is still available.

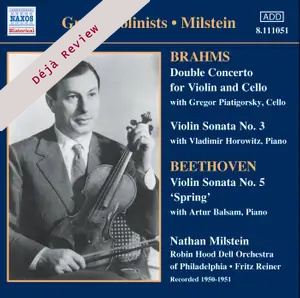

Nathan Milstein (violin)

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Violin Sonata No.5 in F major Op.24 “Spring”

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Violin Sonata No.3 in D minor Op.108

Concerto for Violin and Cello in A minor Op.102

Artur Balsam (piano: Beethoven)

Vladimir Horowitz (piano: Brahms)

Gregor Piatigorsky (cello)

The Robin Hood Dell Orchestra of Philadelphia/Fritz Reiner

rec. New York 1950 (sonatas); June 1951, Philadelphia (concerto)

Naxos 8.111051 [73]

These three recordings were made for RCA Victor in 1950 and 1951, a brief interregnum between Milstein’s Columbia and Capitol years. They pair him with two long-standing colleagues, Piatigorsky and Horowitz, with whom he had many years earlier formed a trio. They also pair Milstein with the loyal Artur Balsam and the Philadelphia, under its nom de plume, directed by Reiner.

Whatever Milstein may have written in his memoirs – liberally drawn on by Tully Potter in his notes – one would never know from his recordings for which works he harboured reservations, resentment or indeed contempt. The memoirs are, it’s true, sometimes remarkable for the disdain in which he held a swathe of concertos and sonatas. He was not committed to all the Beethoven sonatas and was not one to commit full cycles to disc. He evinced interest in only four of them and here we have the Spring with Balsam. A later stereo recording exists of his performance. But fortunately a live Library of Congress performance given by the two men in 1953 – three years later than this studio effort – has been issued on Bridge 9066. It attests to the security of the conception that three movements are almost identical, almost to the second, but that the slow movement, as one might guess, is somewhat more leisurely and relaxed in the Library of Congress – 10:08 to 9:08. The performance generally is a fine one though the caveat is the recording. It was recorded somewhat too “close to the bone” so that accompanying violin figures are elevated to overt statements in their own right, which does little for matters of balance.

Milstein’s phrasing is – one hates to use the word, so much a cliché has it become of his musicianship – aristocratic. He deigns to indulge flashy entries or to over-indulge. Even though the Adagio is quicker than the Library of Congress performance there’s no sense of haste or impatience. Balsam’s pointing is full of incident and deft control. The finale’s wit is, for my taste, rather too reserved but it’s part of a broad ranging conception.

The Brahms sonata pairs Milstein with Horowitz; this was their only collaboration on disc and this is Milstein’s sole commercial recording of the work. The outlines of this are so similar to the Balsam-Library of Congress live reading on the same Bridge disc that housed the Spring that Milstein must surely have strongly dictated the terms of the performance. For those who are interested in such things the differences are a matter of a few seconds. The ensemble between the two men is excellent. Horowitz was an unconvincing interpreter of the concertos, regularly browbeaten by Toscanini into performances that were aligned exclusively to the conductor’s concept. But with Milstein we find a rather different story – superb chording, animation in pedalling, dynamism and verve. Milstein’s subtle vibrato usage is at its height in the slow movement.

The Double Concerto saw Milstein teamed with Piatigorsky, who clearly didn’t share the violinist’s reservations about the work – though to be fair Milstein is hardly the first or last fiddle player to express these kinds of views. The recording has some deficiencies – horns are sometimes strangely “blurry” – but none regarding the performances. Reiner is up to his accustomed level of interpretative insight and Piatigorsky demonstrates his credentials as a Brahmsian. Ensemble work is first class.

For the transfers Producer Mark Obert-Thorn has used a 45-rpm set for the Spring and commercial RCA LPs for the two Brahms. They sound extremely well – full of body and range.

Jonathan Woolf

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free