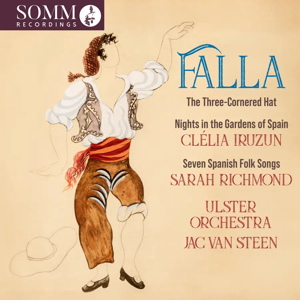

Manuel de Falla (1876-1946)

The Three-Cornered Hat (El sombrero de tres picos) (1919)

Nights in the Gardens of Spain (Noches en los jardines de España) (1916)

Seven Spanish Folk Songs (Siete canciones populares españolas) (1915, orch. 1978, Luciano Berio)

Clélia Iruzun (piano), Sarah Richmond (mezzo-soprano)

Ulster Orchestra/Jac van Steen

rec. 2024, Ulster Hall, Belfast, UK

Spanish texts and English translations included

SOMM Recordings SOMMCD0694 [75]

In this new release from SOMM you might say that Belfast has been temporarily relocated to Andalusia. The Ulster Orchestra and their Principal Guest Conductor, Jac van Steen take us to Spain with a programme of some of Falla’s most attractive and colourful orchestral scores.

The ballet El sombrero de tres picos was written for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes; Raymond Calcraft gives the background – and a good synopsis of the ballet – in his very useful booklet notes. The story is drawn from the novel of the same name by Pedro Antonio de Alarcón (1833-1891); the novel was based on the traditional Spanish folk tale ‘El Corregidor y la molinera’. In fact, Falla first composed a score with the latter title which was staged in Madrid in 1917 as a mime play. After some revisions, the ballet, now bearing the title of Alarcón’s novel, was premiered with great success in Paris by Diaghilev’s company; a little later the ballet was staged in London.

The story of the ballet is an entertaining one in which the lecherous Corregidor is bested by the Miller’s Wife. Falla’s music is just as entertaining. Jac van Steen and the Ulster Orchestra give a performance which I enjoyed very much. The ballet is in two Parts and SOMM helpfully divide the music into eight tracks. That, plus the synopsis, makes it very easy to follow the action. There are two short contributions by mezzo-soprano Sarah Richmond whose voice is very well suited to the music. In Part II, as the Miller’s Wife, she sings the Cuckoo Couplets; in the short Introduction to the ballet, she is the anonymous voice in the distance issuing a warning to the wife. Incidentally, Raymond Calcraft reminds us that Falla added this Introduction for the London production so that the audience had time to admire the drop-curtain, which was the work of Picasso.

In the performance of the ballet highlights include the Dance of the Millers Wife, where a sensual swing of the lady’s hips is audibly apparent. Later, in the Miller’s Dance, her husband struts his stuff in a macho display. After the Magistrate’s Dance the way the self-aggrandising Corregidor falls into the millstream is comically depicted. When one listens to the final dance, this performance brings to life the way the villagers celebrate the fact that the Corregidor has received his comeuppance. Throughout the performance I very much admired the spirited and crisp playing of the Ulster Orchestra – and, as a one-time bassoon player, I must give a special shout-out to the principal bassoonist who characterfully depicts the Corregidor. Jac van Steen conducts very well, although I must admit that there were one or two occasions when I missed the last ounce of Iberian bite and swagger that one gets from the 1981 Charles Dutoit version on Decca (review) while I also have a very soft spot indeed for the version conducted by Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos, which was the first version I owned (on LP) and which I recall as excellent (review). I don’t think van Steen surpasses either of these versions but his is a very good, vibrant account which brings the story vividly to life and gives great pleasure.

It was a shrewd piece of programming to pair Noches en los jardines de España with El sombrero de tres picos on this CD because, as Raymond Calcraft explains, Diaghilev initially approached Falla with a view to using the former as the basis for a ballet. However, Falla was not keen on this idea and proposed instead what became El sombrero de tres picos. In this performance, the soloist is the Brazilian, London-based pianist, Clélia Iruzun. I don’t think I’ve encountered her work before, though from her biography I learned that she has made some previous recordings for SOMM, including a disc of music by Nimrod Borenstein, which was admired by my colleague Jim Westhead (review).

The first of Falla’s three movements depicts the Generalife, the gardens above the Alhambra in Granada. I’ve only ever visited the amazing Alhambra and its surroundings by day; I’d love to experience the whole area on a warm, dark Spanish late evening. Falla’s music is extremely atmospheric – real tone painting – and one can readily imagine, from his depiction, these gardens when the tourists have departed for the day and the night has enveloped the place. In this performance the detail is very well etched in by both the soloist and the orchestra. I think it’s imaginative on Falla’s part that he makes the solo piano important whilst not giving it the dominance of a concerto role. In the second movement, ‘Distant Dance’ there’s admirably nimble playing by Clélia Iruzun and the orchestra matches her dexterity. That runs attacca into the final movement which depicts the Gardens of the Sierra de Córdoba. Here, the pianist is particularly prominent. The music glitters in a way that makes one wonder if this is truly a night piece. I very much admired Iruzun’s pianism; she’s not only highly skilled but also audibly in the spirit of the music. This is an excellent recording of Noches en los jardines de España.

The earliest of these three scores is Siete canciones populares españolas in whichFalla took seven traditional songs from various regions of Spain and arranged them for voice and piano. The songs can, I suppose, be performed individually but when one hears them as a set one becomes aware that there’s an underlying narrative. Until I read Raymond Calcraft’s notes I was unaware that there have been two orchestrations of the songs. One, which I have not heard, is by Falla’s pupil Ernesto Halffter (1905-1989). The other version, which is recorded here, was made in 1978 by Luciano Berio (1925-2003). I strongly suspect that the Berio version was made for his wife Cathy Berberian, though that’s not mentioned in the notes. Berio’s arrangements use a chamber ensemble which includes nine woodwind players, two horns, five brass, two percussionists and timpani. He varies the forces involved from song to song.

Sarah Richmond is an excellent soloist. Her voice is suitably rich and full but the fullness of tone doesn’t get in the way of snappy rhythms. I’m not a Spanish speaker but her enunciation of the words seems very good to me and her singing is consistently characterful. She is crisply supported by the players from the Ulster Orchestra. I like the way Ms Richmond catches the sultry melancholy of the third song, ‘Asturiana’. By contrast, immediately before that, ‘Seguidilla murciana’ is lively and witty. The fifth song, ‘Nana’ is a touching little lullaby, beautifully done here. That’s followed by ‘Canción’ which gets a spirited performance; there’s a rather defiant swing to the singing and playing. The cycle doesn’t have a happy ending: in ‘Polo’ Sarah Richmond conveys the bite and anguish in both words and music.

This is a most enjoyable disc, both in terms of the works and the performances. SOMM have presented the music in an excellent fashion; engineer Ben Connellan has managed the recordings very successfully, allowing lots of detail to register – vital in music such as this – while at the same time giving a nice amount of space around the orchestra.

SOMM’s documentation is very good. I’ve already referenced the very useful notes by Raymond Calcraft. The booklet also includes the texts of the seven songs and an English translation; that’s essential with unfamiliar words such as these.

John Quinn

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.