Adolphe Adam (1803-1856)

Giselle – ballet in two Acts (1841)

Choreography by Marius Petipa, after Jean Coralli and Jules Perrot

Additional choreography by Rachel Beaujean and Ricardo Bustamante

Giselle – Olga Smirnova

Albrecht – Jacopo Tissi

Hilarion – Giorgi Potskhishvili

Myrtha – Floor Eimers

Dutch National Ballet

Dutch Ballet Orchestra/Ermanno Florio

rec. 2023, Dutch National Opera and Ballet, Amsterdam

BelAir Classiques Blu-ray BAC525 [115]

Reviewing a modernised and radically iconoclastic production of Giselle by Swedish choreographer Mats Ek in 1999, ballet critic Clement Crisp was provoked to considerable irritation by the way in which the much-loved classic had been tampered with. He was, indeed, sufficiently cross as to lay down the law. “The ballets of the 19th century”, he wrote, “are windows on to a past which is as frail, artistically, as any endangered piece of nature today, and as deserving of care and conservation. Clever-dick producers who mess with these works, decoding, exploiting and deconstructing them for their own crass ends, are no better than the vandals who pillage archaeological sites or despoil a natural habitat with buildings. The old ballets respond to loving conservation. They live again – and gloriously so – through sensitivity to their style and ambience, and through the genius of great dancers” (Clement Crisp reviews: six decades of dance ed. Gerald Dowler [London, 2021], p. 269). Anyone sharing the late and much-missed Mr Crisp’s outlook can be reassured that there is nothing in this newly-released filmed performance of Giselle to cause any unease – though it does, as we shall see, pose a particularly intriguing question, albeit one of a commercial rather than an artistic nature.

Back in 2009, I added a Warner Classics Blu-ray release (50-51865-7148-2-8) to my collection. It memorialised a Dutch National Ballet production of Giselle that had been given its premiere that very year. The star dancers in that particular performance were Anna Tsygankova as the eponymous heroine and Jozef Varga as her deceitful-then-remorseful lover Count Albrecht. They were very well supported by Igone de Jongh as Myrtha, queen of the ghostly Rhineland wilis, and Jan Zerer as Albrecht’s love-rival, the gamekeeper Hilarion.

The BelAir Classiques disc now under review preserves a subsequent 2023 performance of that very same 2009 production, once again featuring Marius Petipa’s 19th century choreography, sensitively augmented by that of Rachel Beaujean and Ricardo Bustamante. Designers Toer van Schayk and James F. Ingalls are, as in 2009, still responsible for, respectively, the sets/costumes and the lighting. Naturally enough, however, this 2023 performance boasts a brand new cast. There is also a new conductor and a different director for TV and video. At first sight, the orchestra, too, seems a new one, for the place of 2009’s Holland Symfonia appears to have been taken in 2023 by the Dutch Ballet Orchestra. In fact, however, both are simply different incarnations of the same body that had changed its name in the intervening years. You might also quite reasonably assume that there’s been a change of venue, for the Warner Classics disc’s rear cover states that the 2009 performance was given in the Amsterdam Muziektheater, while the new disc’s documentation informs us that the one dating from 2023 was given at the Dutch National Opera and Ballet. However, in reality both stagings took place at the same location, for the performance space itself had also succumbed, meanwhile, to the Amsterdammers’ apparent fondness for adopting new names.

Of the world’s leading dance companies, only London’s Royal Ballet has persisted, in these economically uncertain times, in releasing multiple versions of identical productions so as to showcase different dancers as they take on the leading roles. Keen balletomanes certainly appreciate that policy as they delightedly snap up every filmed performance that comes onto the market. However, most collectors are, I suspect, more than happy with just a single version of any particular production, meaning that sales of subsequent differently-cast ones may well be smaller than those of the original release. The regrettable failure of other ballet companies to follow the Royal’s example is, therefore, perfectly understandable on the grounds of cost. Consequently, the intriguing commercial question to which I earlier referred is “Why has Dutch National Ballet chosen to replicate its repertoire on disc now, when it hasn’t done so before?”

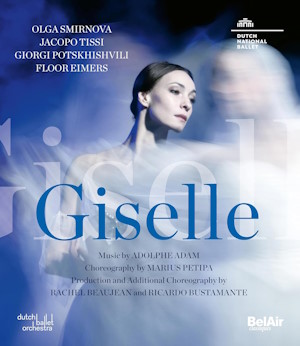

I suspect that the answer may be a relatively straightforward one. In March 2022, just a few weeks after Russia invaded Ukraine, Olga Smirnova, a Bolshoi Ballet prima ballerina of Ukrainian heritage, left that company in protest at the war and joined Dutch National Ballet as a Principal Dancer. Widely recognised as one of the Moscow company’s finest artists, she was a major catch and the temptation to capitalise on her unexpected, but very welcome, arrival may have proved irresistible for the Amsterdam company’s beancounters. Significantly, whereas the 2009 Blu-ray’s cover had featured an image of both Anna Tsygankova and Jozef Varga, the new release’s cover photograph shows Ms Smirnova alone, caught on camera as she emerges, dreamily and ethereally, from a supernaturally wili-esque haze.

As this filmed performance conclusively demonstrates, Ms Smirnova exhibits an assured technique of the highest order. Her consistently deployed skills no doubt explain why, as far back as 2013, The Independent’s critic Zoë Anderson’s pointed out admiringly that “[h]er technique is strong, with fluent line and strongly-controlled turns, matched by distinctive stage presence”. At the same time, Zoë’s counterpart at The Guardian, Luke Jennings, described Ms Smirnova as simply “the physically perfect instrument of her art form”.

As this filmed performance conclusively demonstrates, Ms Smirnova exhibits a totally assured technique of the highest order. Her remarkable career history suggests, however, that we ought to have expected nothing less. Ever since her 2011 graduation from the Vaganova Academy – after which the Bolshoi immediately snapped her up as a soloist without requiring her to work her way up through the corps de ballet – she has garnered a series of remarkable reviews. In 2013, for example, The Independent’s critic Zoë Anderson pointed out admiringly that “[h]er technique is strong, with fluent line and strongly-controlled turns, matched by distinctive stage presence”. Meanwhile, The Guardian’s Luke Jennings was even more enthusiastic, describing her as no less than “the physically perfect instrument of her art form”.

Such pointed critical emphasis on physicality and technique might, at this point, lead you to assume that a ballerina’s competency in dancing is of more importance than the standard of her acting – and ultimately, of course, you’d be correct. Sometimes, too, any thought of attempting to portray characters realistically is actually inappropriate. Many, if not all, ballets of the mid-19th century, for instance, were little more than simple pantomimes, majoring on the exhibition of pretty ballerinas’ elegantly displayed and deployed limbs. Dancers were required to display little more acting ability than might have been expected from an ornamental cabbage. However, there is a good reason why Giselle has outlasted its competitors. The absence, in its lengthy first Act, of any appearances by fairies or the like means that, by the time the theatre interval arrives, its compelling story has established real-life characters in whom we can believe and about whom we actually care. It’s a ballet that ultimately packs an authentic, undeniably strong and dramatic punch, to the extent that female dancers regard the role of the betrayed peasant girl as one of the greatest artistic challenges they may ever face. In describing it as simply “the most important role in any ballerina’s career”, the Royal Ballet’s Natalia Osipova (review) is echoing a point made nearly a century earlier by one of the great ballet historians of the 20th century, Cyril W. Beaumont. “…[T]he title role is the most emotionally exhausting of all parts in the repertory of classical ballet”, he wrote, “for that character is to the danseuse what Hamlet is to the actor. It is imperative that the interpreter of Giselle shall be not only a dancer equipped with a first rate technique, but one able to mime moments of comedy and tragedy; moreover, she must be able to act while dancing.” (Cyril W. Beaumont Complete book of ballets [London, 1937], p. 165).

The importance of acting the role has also exercised the mind of the doyen of living British choreographers. Sir Peter Wright, a man who knows everything there is to know about putting Giselle on the stage, is surely correct when he stresses the importance of “the contrasts of character between the Acts… [S]ome Giselles… tend to be too romantic in the first Act so there is not enough contrast with the second in which she becomes a spirit” (Peter Wright Wrights & wrongs: my life in dance [London, 2016], p. 64). One of the most effective interpretations that I’ve seen has been that of the aforementioned Ms Osipova who successfully conveys an endearingly skittish, buoyant impression in Act 1 before most convincingly transforming herself into an unearthly spirit after the theatrical interval. On re-reading Wrights & wrongs, I was reminded that Sir Peter also rates her performance of the role – not just as a dancer but as an actor too – as at the highest level. He recalls that “the Giselle to move me most is Natalia Osipova (review). She absolutely bowled me over. She was special because she gave the impression of completely immersing herself in the role. She has the most impressive classical technique but makes it speak. She looks like a peasant girl dancing…” (op. cit., pp. 251-252).

Moving on to consider Ms Smirnova’s performance on this new release, I might have had an equally positive response had I only seen the outstanding performance that she gives in Act 2. If you have clicked on the link to Zoë Anderson’s aforementioned review, you will have seen that it was headlined “The Bolshoi’s Olga Smirnova is precise and otherworldly”. Those are well-chosen words, for Ms Smirnova certainly does “otherworldly” very effectively indeed. Giselle’s first Act, however, is an altogether different kettle of fish and surely benefits from a very different approach. The most convincing explanation of Albrecht’s attraction to a lowly peasant girl is not simply that she is physically desirable – for in that case wouldn’t he have simply exercised his droigt de seigneur? – but that he has been attracted by her vivacious personality. Giselle is not a stuffy, entitled aristocrat of his own class, buttoned-up both literally and figuratively, but a young girl revelling spontaneously in her first – and, ironically, life-affirming – discovery of romantic love.

Indeed, the impact of the whole ballet is undeniably enhanced by emphasising the huge gulf between Giselle’s sunny, upbeat existence in Act 1’s “real” world and its bleakly sombre equivalent in Act 2’s hereafter. Ms Smirnova gives us, however, a rather too cool and dreamy interpretation of her role in that first Act. Quite simply, her portrayal of the living Giselle seems a little too measured and calculated. The Variation de Giselle,for instance, a number danced just before Act 1’s Galop general where the girl ought to be at the highest point of her happiness, lacks a real sense of joyful spontaneity. Ultimately, I find Ms Smirnova’s insufficiently spirited performance to be tonally too similar to her (undeniably very effective) Act 2 account of Giselle as a condemned-to-life-in-death member of Myrtha’s murderously vengeful cohort.

In all fairness, I ought to point out that, reviewing this same performance on its original worldwide transmission to cinemas, my colleague Jim Pritchard did not share my reservations about Ms Smirnova’s performance. I do suggest that you read his Seen and Heard International piece for an alternative point of view. I am, however, quite at one with Jim when he suggests that Jacopo Tissi’s somewhat cool and detached performance as Albrecht is “rather dramatically inert”, even though it is hard to find any fault with his very impressive technique as a dancer. When both Giselle and Albrecht are portrayed in such similarly restrained ways, it’s hard to work up much sympathy for their romantic predicament. One begins, indeed, to root for Hilarion, the only one of the love triangle with a bit of passionate oomph about him.

The roles of both Hilarion and Myrtha are strongly cast in this performance. Apart from the Act 2 episode where Hilarion is killed, the gamekeeper’s role involves more acting than dancing, but Giorgi Potskhishvili makes a strong impression on both counts. I can give no higher praise than to say that he’s almost up there with the charismatic Vitaly Biktimirov who takes the role in a superb Bolshoi Ballet Giselle from 2011 (BelAir Classiques BAC474). As the queen of the wilis, Floor Eimers is appropriately frightening, aloof and unforgiving, even if she doesn’t quite match the outstanding performance given by Igone de Jongh, her 2009 Dutch National Ballet predecessor. The peasant pas de deux, often a showcase for new and upcoming company members, is danced here by two couples, necessitating a couple of new solo numbers which have both been given to the women. I don’t recognise the interpolated music but it certainly fits more than acceptably into the usually-heard Adam score and may well, I imagine, have been lifted from one or other of the composer’s 13 other ballets.

The members of the corps de ballet have plenty to do in Giselle. In Act 1 they mill busily around, giving a good impression of informal spontaneity, whether as simple, hearty villagers or members of the aristocratic hunting party. After the interval, as you would expect, the women are marshalled on stage with greater linear precision (Queen Myrtha clearly runs a very tight ship) as 24 ghostly wilis and Amsterdam mounts one of the best-looking productions of the second Act that I’ve seen. The players of the Dutch Ballet Orchestra, conducted by Ermanno Florio with close attention to, and consideration for, the dancers, does an excellent job. Quite rightly, they draw attention to themselves only at the point when they’re inevitably brought to our attention by playing those unfamiliar new melodies in the peasant pas de deux.

Toer van Schayk’s set is the conventional one for Giselle, with mother’s cottage on one side of the stage and Albrecht’s on the other. The usual country road runs along the back, allowing the villagers and hunters to enter and exit as required. The costumes are, however, worth a specific mention. Particularly taken with the “traditional pastel-shaded dirndls and lederhosen”, my colleague Jimthought the outfits “typical of late medieval times”. That’s generally true of the peasant characters, even if cynics might query why they look so free of tears, patches, dirt, blood and all the other filth of everyday rural life (and they can’t be Sunday-best outfits, as surely no hunting party would be out and about on the Sabbath). There is, however, a bizarre chronological mis-match between the peasants’ outfits and those worn by the ducal entourage, for the toffs’ couturier seems to have been cutting and sewing about three centuries later: imagine the cast-offs from a production of Andrea Chenier and you will immediately get the point. Whatever the case, the eclectic mix of on-stage costumes simply looks rather pretty. Jim, indeed, considered the outfits “exquisite”.

Meanwhile, James F. Ingalls’s lighting design is difficult to fault. While never compromising the balance of light and shade that adds both visual interest and vital theatrical atmosphere, his expert work allows us to see everything that we need to – even in Act 2’s dark, spooky graveyard-cum-forest-glade that’s sometimes heavy with dry ice. Isabelle Julien’s direction for TV and video skilfully captures any particular bits of stage business that need emphasising, so that no important plot points are missed. On one or two occasions, fast lateral panning as the camera tracks a quick-moving dancer across the stage renders background characters’ movements fuzzy or a little jerky. Regular readers will recognise that as an issue that occasionally arises with Blu-ray releases, but, on balance, I still find that the superior technology’s benefits outweigh its occasional glitches. Indeed, I continue to hope that the fault lies in playback mechanisms rather than the discs themselves and that one day I’ll be able to achieve perfect reproduction from all my discs.

This, then, is a release that has a great deal going for it. Unfortunately, it faces competition from the same ballet company’s aforementioned 2009 performance which I find a rather more involving one. There are plenty of fine versions from elsewhere too. You will find three from the Royal Ballet alone – featuring Alina Cojocaru/Johan Kobborg (2006), Natalia Osipova/Carlos Acosta (2014) and Marianela Nuñez/Vadim Muntagirov (2016, available on Opus Arte OA BD7216 D). Other recommendable Blu-rays also deliver fine performances, including the previously referenced Bolshoi one, which stars Svetlana Lunkina and Dmitry Gudanov, and another from the Paris Opera Ballet that was filmed in 2006 with Laëtitia Pujol and Nicolas Le Riche in the leading roles. All those – and other performances too – should also be available in standard DVD format. Any balletomane in search of an ideal Giselle certainly needs no excuse to go on adding new releases to their collection whenever – and in whatever format – they appear.

Rob Maynard

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free

Other cast and production staff

Wilfried, Albrecht’s friend – Rémy Catalan

Duke of Courland – Nicolas Rapaic

Berthe, Giselle’s mother – Jane Lord

Bathilde, Albrecht’s fiancée – Erica Horwood

Pas de quatre – Yuanyuan Zhang, Naira Agvanean, Edo Wijnen and Sho Yamada

Giselle’s girlfriends – Yvonne Slingerland, Inés Marroquin, Alexandria Marx, Arianna Maldini, Luiza Bertho and Kira Hilli

Peasant girls – Bo-Ann Zehl, Mila Nicolussi Caviglia, Catarina Pires, Laura Rosillo, Beatriz Kuperus, Louisella Vogt, Koko Bamford, Antonina Tchirpanlieva, Poppi Eccleston, Sebia Plantefève-Castryck, Emma Mardegan and Hà Nhi Trân

Peasant boys – Manu Kumar, Daniel Robert Silva, Francesco Venturi, Sven de Wilde, Fabio Rinieri, Rafael Valdez Ramirez, Leo Hepler and Bela Erlandson

Wine stampers – Sem Sjouke, Dingkai Bai, Koyo Yamamoto and Soshi Suzuki

Master of the hunt – Conor Walmsley

Hunting party, young noble lady – Amelia Bron

Hunting party – Liza Gorbachova, Gabriel Rajah, Frédérique Meewis, Luca Abdel-Nour, Nicola Jones, Robin Park, Annabelle Eubanks, Alexander Álvarez Silvestre, Ella Kolpakov and Patrik Benák

Hunting party, pages – Luc Smit and Bram van Espen

Hunting party, servants – Edwin Boer and Nico Weggemans

Wild boar bearers – Hans van Rijswijk and Henk Melchers

Villagers – Yolanda Germain, Floor Scholten, Evelien Emmens, Esther Jager, Robin van Zutphen and Matthew Kelly Roman

Moyna – Nina Tonoli

Zulme – Naira Agvanean

Wilis – Mila Nicolussi Caviglia, Arianna Maldini, Yvonne Slingerland Cosialls, Sangwon Park, Emma Mardegan, Frédérique Meewis, Inés Marroquin, Catarina Pires, Anaëlle Tran, Luiza Bertho, Sebia Plantefève-Castryck, Laura Rosillo, Alexandria Marx, Beatriz Kuperus, Victoria Glazunova, Nicola Jones, Elin Borgman, Kira Hilli, Antonina Tchirpanlieva, Koko Bamford, Louisella Vogt, Liza Gorbachova, Poppi Eccleston and Ella Rose Churchill

Set and costume designer – Toer van Schayk

Lighting designer – James F. Ingalls

TV and video director – Isabelle Julien

Technical details

Picture format: 1 BD 50, NTSC, 16:9

Sound format: PCM Stereo 2.0 and DTS-HD MA Surround 5.1

Region code: A, B, C