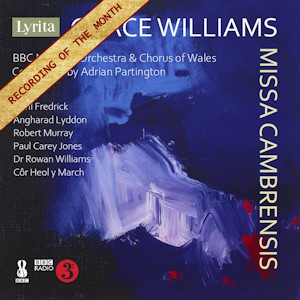

Grace Williams (1906-1977)

Missa Cambrensis (1970)

April Fredrick (soprano); Angharad Lyddon (mezzo soprano); Robert Murray (tenor); Paul Carey Jones (bass); Dr Rowan Williams (narrator)

Côr Heol y March

BBC National Orchestra and Chorus of Wales / Adrian Partington

rec. 2024, Hoddinott Hall, Cardiff

Texts & English translations included

Lyrita SRCD442 [67]

A number of works by Grace Williams have appeared on CD in recent years, with Lyrita leading the way, as they so often do with British music. However, there’s been nothing on the scale of this first commercial recording of her Missa Cambrensis. This Latin setting of the Ordinary of the Mass was composed between 1968 and 1970; it was one of her last works and I think it’s legitimate to consider it as her magnum opus. To the best of my knowledge, the work has only had two performances. It was premiered in Llandaff Cathedral, Cardiff in June 1971, as part of the Llandaff Festival (which had commissioned the work), by the BBC Welsh Symphony Orchestra and the Llandaff Cathedral Choral Society. The conductor was Robert Joyce and the soloists were Janet Price, Rhiannon Davies, Kenneth Bowen and John Barrow. Though Missa Cambrensis attracted some respectful press comment at the time it had to wait a very long time for a second hearing. On 1 March 2016 (St David’s Day), the same orchestra, now renamed the BBC National Orchestra of Wales (BBCNOW) and joined by the BBC National Chorus of Wales (BBCNCW), performed it in St David’s Hall, Cardiff as part of a concert which was broadcast on BBC Radio 3. That broadcast allowed me to hear the work for the first time. Neither the conductor nor any of the solo quartet who took part in that performance are involved in this Lyrita studio recording but one person is common to both: Dr Rowan Williams, the retired Archbishop of Canterbury, here reprises the role of the narrator which he took in 2016.

Missa Cambrensis is an ambitious work, which in this performance plays for 67 minutes. It is scored for SATB soloists and choir, a narrator, a children’s choir and a large orchestra. The orchestration is as follows: 2 each of flutes, oboes and clarinets (with the usual doublings), 2 bassoons and a contra; 4 horns, 2 trumpets, three trombones, tuba; timpani; percussion (2 players); piano, strings and harp. (The harp is only involved in the ‘Carol Nadolig’ movement, in which it accompanies the children’s choir.)

In listening to the work for reviewing purposes I’ve had access to a vocal score. As a result, I’ve been able fully to appreciate just how challenging the work is, especially for the chorus. The vocal writing is often complex and highly chromatic, though I should say at once that the chromaticism and other complexities are used, I believe, not gratuitously but entirely for expressive effect. The soloists don’t have any aria-like solos; rather, they tend to sing as a team, either in conjunction with the chorus or as a quartet. All of the solo parts cover a very wide compass, especially the soprano and tenor, and the tessitura is often challenging for all four soloists. Their roles are complex and the harmonic writing must make pitching a challenge – a challenge which these soloists meet completely. I was very impressed by all four of them.

The opening of the Kyrie is marked solenne; the music is slow and seems to me to be full of apprehension. The choral writing is challenging right from the start; note, for example, the strange, unprepared chords on the last syllable each time the choir sings ‘Kyrie eleison’. We first hear the soloists at ‘Christe eleison’, where their music is impassioned. Throughout this movement the thematic material may appear fairly limited but, as such, it imprints on the listener and so it’s effective. Missa Cambrensis is thus impressively launched.

The Gloria begins in an extrovert fashion, though that mood doesn’t last long. The ‘Laudamus te’ section, which is introduced by the soloists, is appreciably slower; here the solo singers have winding, chromatic lines and the tessitura is often testing. The next section, ‘Domine Deus’ presents formidable challenges to the performers and I very much admired the skill and commitment with which all of them deliver this music, under the expert guidance of Adrian Partington. Later in the movement, the ‘Qui tollis’ section again features the soloists, who make a fine impression. Relatively speaking, the music is in calmer waters at that point. Towards the end, in the ‘Cum sancto’ episode, Williams gives the choir vigorous contrapuntal writing, built on a single melodic cell. The difficulties of this passage are compounded by the fact that the music bristles with accidentals but the singers of the BBCNCW meet the challenges head on – and successfully.

It seems to me that the Credo is the most interesting movement in the whole work. Throughout Missa Cambrensis Grace Williams responds to the text of the Mass in a most original and thoughtful fashion and that’s especially true of her approach to the Credo. The very opening commands close attention because this is no confident expression of faith. Rather, the music is slow, hushed and full of suspense. I sense quite a degree of uncertainty, which is enhanced by the dark colours in the orchestral scoring. Williams sustains this approach through to the ‘Et incarnatus’, at which point the very hushed music definitely conveys wonder and awe. Then comes Grace Williams’ structural masterstroke.

As Paul Conway explains in the booklet essay, Williams wanted to devise her setting of the Credo in such a way as to separate the references to Christ’s birth and death. He quotes a brief extract from a contemporaneous letter in which she stated ‘I’ve always been puzzled by the nativity being followed immediately by the crucifixion’. Her solution was to insert two very different interpolations, both in Welsh. The first of these is ‘Carol Nadolig’ (Christmas Carol). This is a piece which Williams composed in 1955 to words by Saunders Lewis (1893-1985), the Welsh poet, man of letters and a co-founder of the Welsh nationalist political party, Plaid Cymru. Lewis’s words are set here for a 3-part children’s choir (SSA). The music is pure and innocent, as is the sound made by the young singers of Côr Heol y March. They are accompanied by a harp, which emphasises the simplicity and Welshness of the setting. The children sing really well; not only do they produce a delightful sound but they’re also very accurate in terms of rhythms and dynamics. Clearly, they have been very thoroughly prepared for this assignment by their musical director, Eleri Roberts who founded the choir in 2009, The soloists and adult chorus sing an awestruck ‘Et homo factus est’, following which there is a brief, very effective reprise of the carol. The second interpolation follows. This is a spoken recitation, in Welsh, of the Beatitudes from St. Matthew’s Gospel. The speaker is Dr Rowan Williams. His voice will be familiar to many from his time as Archbishop of Canterbury (2002-12). His delivery is mellifluous and poetic, yet there’s also more than a touch of firmness; I think he’s ideally cast. He speaks against a deliberately sparse accompaniment; oboe and strings provide short but rather lovely phrases between each Beatitude. These two interpolations have a very strategic role in the structure of Grace Williams’ setting of the Credo: in addition, they give the work a decidedly Welsh flavour, something that would have been extremely important to this composer, who was so proud of her Welsh nationality. The ‘Crucifixus’ is taken attacca after The Beatitudes. Here, the music is slow and very intense. The soloists take the lead, singing dramatic music while the chorus are in the background; the writing for the orchestra is very tense. I don’t know if there was an intention on Grace Williams’ part but it seems to me that this section of her Credo, from ‘Et incarnatus’, through the interpolations and on to ‘Crucifixus’, presents something of a microcosm of Christ’s life: his birth, an example of his teaching and his death, I may be mistaken in that thought, but whether that’s the case or not I think this extended section is both imaginative and effective.

‘Et resurrexit.’ follows. Again, the treatment of the text is unconventional and personal. The Resurrection is not celebrated joyfully; instead., Williams sets the words to slow, quiet music sung by the soloists, whose parts are marked molto misterioso. (It’s noteworthy, I think, that misterioso is a marking that Williams uses quite frequently.) It’s not until the Ascension is reached that the music becomes both louder and quicker. Williams reprises the opening of the Credo to telling effect and then gradually builds to a big climax at ‘Et expecto’. There’s a great deal of struggle during this setting of the Credo but Williams brings it to a major-key conclusion; the movement ends with a short ‘Amen’ in the key of F# major. I’ve deliberately spent a lot of time on the Credo because I think it’s a compelling movement and, moreover, it seems to me to be the philosophical key to Missa Cambrensis. I’m struck by how much music in this movement is in slow tempi and by the number of times that Grace Williams surprises through unusual but very effective treatments of the words.

At the start of the Sanctus we hear distant trebles, echoed, more loudly, by the soloists. Hereabouts, I was put in mind of Britten’s War Requiem. The ‘Hosanna’ is set to big, proclamatory music. The quiet ending, at which point the trebles return, is effective and lovely. There’s an extended orchestral introduction to the Benedictus. The marking is interesting: Moderato tranquillo, alla marcia ma leggiero. Despite the alla marcia element in that injunction the music is quite gentle; the woodwinds, and the oboe in particular, are prominent here. The movement is founded on a basic melodic cell, which is first sung by the soloists, then by the choir; this cell is quite simple but striking. The Benedictus is largely subdued in character and, tellingly, there is no ‘Hosanna’ at the end.

The Agnus Dei follows without a pause. The movement opens with an impassioned soprano solo which April Fredrick delivers thrillingly. She is followed in like vein by her three colleagues. At this point. the orchestral accompaniment features jagged rhythms. Most of this movement is led by the soloists and Grace Williams makes this into a genuine, rather fearful plea for mercy. ‘Dona nobis pacem’, which Williams designed as a clear sub-section of the Agnus Dei, follows without a break. When the choir begins this section I noted with interest that their phrases are marked sensa misura (as in plainsong). Given the sinuous, chromatic nature of the writing and the need to dovetail the various lines I’m not sure that senza misura is an instruction that could be taken too literally; the music might fall apart. What I suspect it means is that Williams wants a seamless flow in the singing and that’s certainly achieved here, both by the choir and, in due course, by the soloists. The pace is very measured and the music is subdued, with an ominous tread in the orchestra. Eventually, the orchestra attains a substantial climax, based on the opening of the Kyrie, which then subsides to nothing. Then, intriguingly, Williams reprises the lively opening of the Gloria. This is marked for the children’s choir to sing (in four parts) but on this occasion it’s the sopranos of the BBCNCW who do the honours; that’s a logical departure from the printed score, I believe, since it’s the adult voices who sang this material when it first appeared. I must confess that I’m slightly puzzled as to why this reprise is inserted at this point, but since the composer has so clearly pondered the text of the Mass very deeply, there will be a good reason for this. There follows an anguished, heartfelt cry of ‘Dona nobis pacem’ in which both the soloists and the choir participate before Williams brings Missa Cambrensis to a very subdued conclusion. She ends on a quiet C major chord, but on this occasion C major seems very uneasy.

After I’d listened to the new recording for the first time, I found in Paul Conway’s booklet essay some quotes from reviews of the premiere of Missa Cambrensis. One extract particularly caught my eye. It came from a Financial Times review by Ronald Crichton who identified in the work “a prevailing mood of apprehension, of worship as it were under threat”. When I thought back to the music I’d just heard this struck me as a very perceptive observation, especially on just a single hearing of the work. I’ve found that Crichton’s view has been borne out on further listening. In this respect – and in other ways too, which I’ve tried to bring out in this review – Missa Cambrensis seems to me to be a unique and remarkable work.

Missa Cambrensis is a work with which it may take listeners some time and effort to come to terms. However, I think it’s well worth that investment. The more I’ve listened to the work the more I’ve become convinced that it’s a work of genuine eloquence and stature. The symphonic nature of the work is apparent after one has heard it a few times: Williams frequently revisits material from earlier in the score in order to provide structural unity and also to reinforce, I think, her philosophical thinking about the text of the Mass. The music is extremely challenging for the performers. A professional orchestra of the calibre of the BBCNOW will take the complex orchestral writing in its stride – and they do that here. However, the BBCNCW is comprised of amateur singers, albeit highly experienced singers of a very high standard. I’m full of admiration for the evident skill, musicianship and commitment they’ve brought to this assignment, as have their younger colleagues in Côr Heol y March. The solo quartet is marvellous. It would be invidious to single out any of them; they work as a team and deliver Williams’ extremely demanding solo parts with eloquence, assurance and significant musicianship. The performance of this very difficult score has been brought together with great skill and understanding by Adrian Partington. Over the years, I’ve reviewed for Seen and Heard a number of Three Choirs Festival concerts at which he’s conducted complex contemporary works such as John Adams’ On the Transmigration of Souls, John Joubert’s An English Requiem and A Song on the End of the World by Francis Pott. He was, therefore, an ideal choice to bring Grace Williams’ magnum opus to life, which he does convincingly.

Producer Adrian Farmer and engineer Simon Smith have done a very good job on the technical side of this recording. Grace Williams’ textures are often very full, teeming with detail. They – and the skilled performers – have ensured that we hear the strands of this score – and the ‘big picture’ – to best possible advantage. My sole reservation is that there were times, the Sanctus being one such, when I wish the adult choir had been brought forward a bit more in the overall sound picture. Paul Conway, as usual, has provided a detailed and authoritative booklet essay which introduces us to this unfamiliar work in an ideal fashion.

It must be highly unlikely that Missa Cambrensis will ever receive a second recording so it’s as well that this premiere recording – which both composer and work thoroughly deserve – is such an excellent one. I urge you to investigate this compelling and profound work through this very fine recording.

John Quinn

Click here to read an interview in which conductor Adrian Partington discusses Missa Cambrensis.

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free