Kurt Weill (1900-1950)

Die Sieben Todsünden (1933)

Vom Tod im Wald, Op.23 (1927)

‘Lonely House’ (Street Scene) (1947)

‘Beat! Beat! Drums!’; ‘Dirge for Two Veterans’ (Four Whitman Songs) (1942-47)

Kleine Dreigroschenmusik (1929)

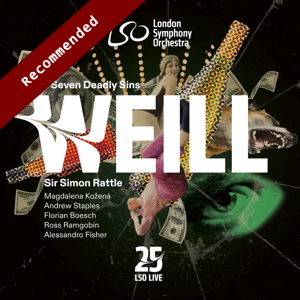

Magdalena Kožená (mezzo-soprano), Andrew Staples (tenor), Alessandro Fisher (tenor), Ross Ramgobin (baritone), Florian Boesch (bass-baritone)

London Symphony Orchestra/Sir Simon Rattle

rec. live, 28 April 2022, Barbican Hall, London, UK

German texts & English translations included

LSO Live LSO0880 SACD [77]

This album forms part of LSO Live’s celebration of the label’s 25th anniversary. Its release in January 2025 may also be intended as an acknowledgement of the seventieth birthday of their former Music Director, Sir Simon Rattle.

These performances of music by Kurt Weill were recorded live at an LSO concert in 2022. The concert was reviewed appreciatively by my Seen and Heard colleague, Mark Berry. I was interested to see from his report that at the concert the pieces were presented in a slightly different order compared to the disc: the concert began with Kleine Dreigroschenmusik and ended with Die Sieben Todsünden; the other pieces were placed as they appear on the SACD. In fact, I’m going to consider the performances largely as they were played in the concert, simply because it seems logical to consider Die Sieben Todsünden as the “main event”.

As David Drew points out in his booklet note, Kleine Dreigroschenmusik is not simply a suite extracted from the 1928 adaptation of The Beggar’s Opera on which Weill and Brecht collaborated with Elizabeth Hauptmann; it’s a concert work in his own right. It’s a piece for which I’ve always had a soft spot ever since I had the chance to take part in a student performance many years ago. On the surface it comprises a series of catchy, memorable tunes but you don’t have to dig far beneath that surface to find something darker, especially given Weill’s piquant, often provocative scoring. This performance shows the LSO at their incisive best and also Rattle’s flair for repertoire such as this. The acerbic nature of Weil’s textures comes out excellently in ‘Overtüre’; the immediacy of the recorded sound is an asset, too. Here, and elsewhere, the crispness of the rhythms is ideal. There’s a good sense of sleaze in ‘Die Moritat von Mackie Messer’ but, in contrast, ‘Polly’s Lied’ is tenderly done. ‘Kanonen-Song’ is fast and furious. On a first hearing, I was momentarily disconcerted by the brisk pace but in fact the biting delivery is ideal and Rattle and his players convey the right sarcastic feel as well as a definite sense of the frantic 1920s. The suite ends with ‘Dreigroschen-Finale’ and here I like the dark, tense way in which the music that precedes the concluding chorale is played. I relished this performance.

Die Sieben Todsünden involves a quartet of male singers and three of them get solo numbers in this programme. Andrew Staples sings ‘Lonely House’ from Weill’s 1947 Street Scene, a show in which he brilliantly fused Broadway and his background in German music theatre. Staples sings the number well. However, comparisons with Jerry Hadley on John Mauceri’s 1989/90 Decca recording of the complete show are not entirely in Staples’ favour. It seems to me that Hadley is more idiomatic – for example in the way he delivers the phrases all on the same note in the song’s preamble. Also, Mauceri adopts a rather more expansive pace than does Rattle and this allows Hadley more space in which to phrase and express this regretful number. Still, heard in isolation, Staples’ performance is good.

Staples also sings one of the two Whitman Songs that Weill composed as a response to the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. (By coincidence, Vaughan Williams set the two poems which are performed here as part of his great cantata Dona nobis pacem, written in 1936.) Staples sings ‘Dirge for Two Veterans’, which Weill sets as a bitter slow march, the music full of urgency. Staples’ singing is eloquent and involving. Ross Ramgobin is allocated ‘Beat! Beat! Drums!’; he sings it crisply and is supported by very incisive playing by the LSO.

The other solo item is Vom Tod im Wald (Death in the Forest), a dark, unsettling setting of a poem by Berthold Brecht which Weill made in 1927. Here the singer is Florian Boesch. In her very good notes Jessica Duchen mentions that this is a Sprechstimme setting. I don’t have access to a score but it seems to me that Boesch actually sings most of the music. The piece is quite short – here it plays for 8:18. It’s also pretty stark; the scoring for just ten brass and woodwind instruments sees to that. It’s anything but comfortable to listen to and it’s certainly a piece that I would admire rather than love. Boesch’s singing is compelling and the members of the LSO back him to the hilt.

Die Sieben Todsünden is a fascinating and unusual work which Weill composed in Paris, immediately after the rise to power of the Nazis obliged him to flee Germany. Once again, he collaborated with Brecht. It turned out to be the last time they would work together and, sadly, it was not a happy experience. As Jessica Duchen points out in her notes, Brecht was far from enamoured of the concept of this Ballet chanté – he had an aversion to ballet – and, as Duchen indicates, he took the job for the money and dashed off the libretto very quickly. The plot concerns Anna, whose family (the male-voice quartet) send her away to earn money so that they can build a house on the Mississippi River. In a staged production there are, in fact, two Annas: Anna I, the singer, and Anna II, her sister who is the dancer; in a concert performance the contributions of Anna II are limited to a handful of brief spoken comments. Anna’s journey takes her through seven American cities in seven years (though time is never defined in the libretto) and along the way she observes seven sins. Her encounters with manifestations of the sins oblige her to choose between what is profitable and what is right.

Just recently I had the opportunity to review another new recording of Die Sieben Todsünden; this one, conducted by Joana Mallwitz, was made in Berlin with Katharine Mehrling as Anna. Though I don’t propose to do a detailed comparison, the Berlin and London recordings are quite distinct from each other. Both recordings benefit from excellent orchestral playing. I wouldn’t want to suggest that the LSO is “better” than the Konzerthausorchester Berlin but I think that the LSO’s playing is a bit more edgy and that edginess is emphasised by the somewhat more immediate recorded sound on the LSO disc – an immediateness which I think is entirely appropriate in this instance. Theres also the question of the conducting. I admired Joana Mallwitz’s direction of the score – I still do – but it seems to me that Rattle often brings an even greater degree of intensity. As an example, there’s an almost Mahlerian depth to the playing at the start of ‘Envy’. (Incidentally, there’s a similar quality in the same passage in the EMI recording he made as long ago as 1982 with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra.) Earlier in the work, Rattle inflects the sardonic waltz rhythms of ‘Pride’ with great character. The urgency his conducting brings to ‘Anger’ helps the male singers to put across their music with burning conviction. Listen out, also, to the way instrumental detail contributes significantly to the biting performance of ‘Lust’.

The main difference between the two recordings, however, lies in the way the role of Anna is put across. The score was originally conceived with a soprano voice in mind. However, as Jessica Duchen reminds us, when Lotte Lenya revived Die Sieben Todsünden after her husband’s death the role was transposed down to suit the lower compass of her voice. In Rattle’s 1982 recording the role of Anna was taken by the soprano Elise Ross; I believe that may have been the first recording of the work with the role of Anna at the original pitch. On the Mallwitz recording Katharine Mehrling uses the lower transposition. Since Magdalena Kožená is a mezzo, I had thought that she might follow Mehrling’s example. However, from A/B comparisons of the three recordings it seems to me – I say seems because I don’t have perfect pitch – that Kožená sings the high-voice version. The higher-lying line causes her no problems at all; perhaps that’s not entirely surprising because she began her career as a soprano. But the differences between Mehrling and Kožená go well beyond the question of the lie of the vocal line.

As I commented in my review of her recording, Mehrling has significant experience of performing Weill at the Komische Oper, Berlin with the director Barrie Kosky She draws on that experience to give a very theatrical performance which is right in the Lenya tradition; I hasten to say that I enjoyed it very much. Kožená draws on a more “conventional” concert hall and operatic hinterland. Very wisely, in my view, she doesn’t attempt a Lenya-style delivery. Instead, she gives a performance of the part that is largely sung, though she does deploy Sprechstimme-style delivery at times – its rarity makes it stand out very effectively in her performance. However, those who are familiar with the work of this artist won’t be surprised to learn that her singing is, in its different way, just as intense and expressive as is Merhling’s performance. So, for example, I find Kožená’s account of ‘Lust’ is absolutely riveting. In ‘Envy’ she offers a truly intense performance, as do the LSO. It seems to me that Magdalena Kožená brings the character of Anna vividly to life in all respects.

Perhaps inevitably, I’ve focused on the central character of Anna. I ought to say that the male-voce quartet makes a terrific contribution to the success of the Rattle performance. When we first meet Anna’s family in ‘Sloth’, the way these four singers deliver their music, characterising it very strongly, leaves us in little doubt that these aren’t particularly nice people – and the LSO’s playing reinforces that perception. The quartet are really indignant in ‘Anger’ – Anna and her sibling have really got their backs up with their failure to deliver for the folks back home! Their singing in ‘Greed’ is vivid; there’s a particularly fine tenor solo in this section. At the end, in the Epilogue, Anna tells us that she and her sister have done as they were instructed; the family now have their nice new house. But after hearing the querulous, self-centred contributions of Anna’s family as portrayed here, you rather wish there hadn’t been a “happy ending” for them.

I still admire greatly the Mehrling/Mallwitz recording and I’ll certainly turn to it when I want to hear the role of Anna done in a Lotte Lenya style. However, for the reasons I’ve mentioned already the Kožená/Rattle account is a very fine one and, for me, it has the edge. Rattle conducts the entire programme very well and one thought has crossed my mind: has he ever done the Weill symphonies? If not, I wish he would consider the Second in particular.

The LSO Live recorded sound is vivid and immediate; it suits this music to a tee. The documentation is thorough with excellent notes by Jessica Duchen and, in the case of Kleine Dreigroschenmusik by David Drew. The set has a massive advantage over the Mallwitz DG disc by offering the texts and translations. LSO Live have presented this set in a hardback book-style case, eschewing plastic. I think this is a new departure for them; I like the presentation.

John Quinn

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.