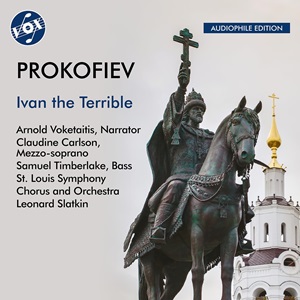

Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953)

Ivan the Terrible – film score, Op 116 (1942-44)

Oratorio for Alto, Bass, Chorus and Orchestra (arr. Stasevich, 1962)

Claudine Carlson (mezzo-soprano)

Samuel Timberlake (bass)

Arnold Voketaitis (narrator)

St Louis Symphony Orchestra and Chorus/Leonard Slatkin

rec. 1979, Powell Hall, St Louis, Missouri, USA

Texts, translations included

Audiophile Edition

Vox VOX-NX-3045CD [72]

As I mentioned in my review of Leonard Slatkin’s Alexander Nevsky and the Lieutenant Kije Suite here, this Ivan The Terrible was originally released with those two works on a three-LP set on Vox in 1981 entitled Prokofiev – Music from the Films. The same three works saw life again on Vox in 1990 on a double-CD set labelled Prokofiev – The Film Music. Abram Stasevich, who arranged music from the two parts of the film about Ivan the Terrible for this oratorio, was the first to record it (1968 on Melodiya). Riccardo Muti followed in 1978, and then came Slatkin. Other recordings would come along soon after, and I’ll write more about that later.

This Ivan performance employs the rather superfluous narration by Stasevich (but in English, thankfully), while the 1990 CD account eliminated it altogether. I’m not sure why this reissue has it restored, since the narrator intrudes on the music in several places and extends the length of the work unnecessarily. The Neeme Järvi Ivan on Chandos excised the narration by using a version fashioned by Christopher Palmer that was based on Stasevich, but with some of the music cut. I’ll have more to say on this when I make comparisons later on.

Leonard Slatkin clearly demonstrates here that he knows this score as well as anyone, and the St Louis Symphony Orchestra, over which he would preside as music director from 1979 to 1996, plays splendidly for him. The Orchestra’s chorus also turns in fine work throughout. Slatkin’s tempo choices almost unerringly fit the character of this colourful but often dark music. Try the opening number, Overture and Chorus, where the Ivan theme is proudly announced by the brass accompanied by scurrying strings, which then leads to the chorus declaring, “Black clouds menacing, surge unendingly, blood-red crimsoning the sunrise…” Throughout this first track the music pulses with kinetic energy as the orchestra proclaims the glories of Ivan while in contrast the chorus sings of blood and oppression with an ominous sense amid rhythmic spirit and trenchant accents. This choral theme is one of those memorable Prokofiev creations that seem to spring from its rhythms.

The third number, Ocean – Sea, also features another arresting melody. It is scored for alto soloist, chorus and orchestra, and here sung quite beautifully by Claudine Carson. This music reappears in No 7 but is shortened. No 9, Simpleton, is one of the best numbers that feature only the orchestra. Here the brass play with precision while managing to impart a truly wanton spirit, this latter aspect especially noticeable in the grunts and jabs from the trombones and tuba. The strings cut into the sonic fabric, seemingly spurred on by the sassy xylophone. It’s quite a bold mixture of utterly colourful and dynamic music.

The angelic choral style of No 10, The White Swan, and the lushly Romantic manner of No 11, Glorification, are very beautifully sung here, probably unsurpassed in any other recording. One of the most popular numbers in this work is No 15 Cannoneers (or Gunners), with its catchy melody and rhythms and the often repeated word “pushkari” (gunners) fitting in so well with the driving, exuberant music. No 16, To Kazan, at ten minutes, is the longest track and contains some of the best music. The opening features a truly grotesque yet thoroughly compelling number for tuba and orchestra. Then, in stark contrast, it is soon followed by what is probably the most famous theme in the work, one that you may know from Prokofiev’s opera War and Peace, where it closes the work with a grand triumphant chorus. Here it appears in a more warmly lyrical style, especially in the so-called humming chorus which comes in the latter half of No 17, Ivan Pleads with the Boyars. All of this music is performed so well here. Other outstanding numbers include The Song of Feodor Basmanov (No 23), sung here in a rollicking and most convincing manner by Samuel Timberlake, and the simply brilliant and magical Dance of the Oprichniki (No 24), which might just remain in your mind’s ear for hours after a single hearing.

Slatkin adds a Polonaise on track 25 from the original film score, but a more extended version of it was used by Prokofiev for Boris Godunov, Op 70 bis. Slatkin and company offer a fine account of this brief dance. The ensuing track, Finale, closes out this oratorio in grand style, the performance by chorus and orchestra excellent once again. Overall, this performance is a triumph for all parties involved.

The sound reproduction is well-balanced and vivid. Once more, as I mentioned in my review of Alexander Nevsky and Lieutenant Kije referenced above, the notes by the late Richard Freed make a claim about the orchestration that I must take issue with (see the note below). Freed is otherwise quite informative and thorough in his essay.

As for comparisons with other performances, I’ve already mentioned the quite fine Järvi effort on Chandos, but there are several others of note. The Michael Lankester version, recorded by Rostropovich with the LSO on Sony, has even more narration (in English) than the Stasevich and thus unfortunately extends the work to over ninety minutes, making it about a half hour longer than versions without narration. There is a very interesting account on RCA/BMG led by Dmitri Kitayenko with the Frankfurt RSO, but good as it mostly is, some tempos are simply too slow. Muti on EMI with the Philharmonia, using the Stasevich arrangement and narration, is quite good, most notably in the orchestral playing. But there are some imbalances in the sound, especially in the rumbling of the bells in many numbers and in the fuzzy sound of the chorus, which seems to be pushed too far into the background.

In 2019, I reviewed Gergiev’s live Ivan performance here. It is on video (Arthaus Musik) and quite fine but, alas, housed in a four disc box with the symphonies, concertos and other works. Some recordings of Ivan to avoid are two substandard live efforts: the Maxim Shostakovich on Inta’glio and the Alipi Naydenov effort on Forlane.

Conclusion: Musically, Slatkin’s performance can rival or surpass any other effort on record, probably one of the reasons it was nominated for a Grammy in 1981. Thus, if you want narration, this Slatkin version of Ivan is the clear choice to make.

Robert Cummings

Note:

In a footnote, Richard Freed writes that “Prokofiev did not orchestrate his music for the Eisenstein films himself.” (The referenced films are Alexander Nevsky and Ivan the Terrible). Freed goes on to identify Pavel Alexandrovich Lamm as the orchestrator, whom he says also did the orchestration for other Prokofiev works, including the operas Betrothal in a Monastery and War and Peace. I’ve read elsewhere of these claims that Prokofiev had ghost orchestrators, so let me set the record straight. Prokofiev, who was a master orchestrator, as demonstrated by early works like the Scythian Suite, was also very prolific. It is pretty well known, or so I thought, that in the latter part of his career he developed a unique method of orchestration by reducing it to a sort of “shorthand” form. Then he would have a paid assistant convert it to “long-hand”, that is, to conventional orchestration. That way, the busy Prokofiev could quickly move on to his next project.

To cite just one authoritative source, in the book Sergei Prokofiev – Materials, Articles, Interviews – compiled by Vladimir Blok (Progress Publishers, 1978), Russian composer and musicologist Dmitry Rogal-Levitsky relates an encounter with Prokofiev regarding the manuscript of War and Peace: “He [Prokofiev] handed me several sheets of music paper covered in music written in his firm hand. The manuscript was an extremely detailed score written on several lines, as many as ten or more in places. Everywhere there were notes indicating which instruments should play which passages.” When Rogal-Levitsky said it was complicated, Prokofiev replied, “Not at all! All that has to be done now is to write the parts out on separate sheets of music and everything will be ready. I usually indicate the minutest details in a score like this, and Pavel Alexandrovich [Lamm] simply follows my indications”.

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI and helps us keep free access to the site