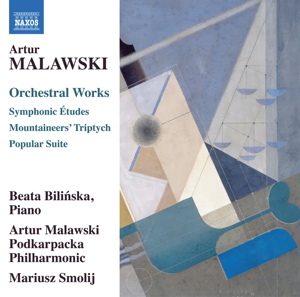

Artur Malawski (1904-1957)

Overture (1948)

Etiudy symfoniczne (Symphonic Études) (1947)

Tryptyk góralski (Mountaineers Triptych) (1949)

Toccata for Small Orchestra (1947)

Suita popularna (Popular Suite) (1952)

Beata Bilińska (piano), Artur Malawski Podkarpacka Philharmonic/Mariusz Smolij

rec. 2024, Malawski Philharmonic, Rzeszów, Poland

Naxos 8.579159 [60]

The name of Polish composer Artur Malawski was previously unknown to me. But given that this valuable overview of his orchestral music is performed by an established symphony orchestra that bears his name, clearly he remains an important figure in Polish cultural life.

Some brief biographical detail might be of use to readers likewise ignorant about him. Malawski’s early musical goal was directed towards being a violin virtuoso. However, a hand injury sustained when he was in his late twenties curtailed that career and he subsequently focussed on teaching and composition. In the former role his pupils included the likes of Penderecki and Wojciech Kilar alongside conductors Jerzy Katlewicz and Jerzy Semkow. He died suddenly aged just 53 years. There does not appear to be a website dedicated to Malawski but on the Polish Culture site there is a more extended biographical note and list of major compositions. Given Malawski’s status in the musical life of Poland in the decade or so after the end of World War II it is something of a surprise that his music is not better represented in the recorded catalogue. A quick look at Discogs suggests that this Naxos disc is the first and only one to be wholly devoted to his orchestral music. As a composer, his creative life lasted less than two decades from his graduation from Kazimierz Sikorski’s composition class in 1939 to his untimely death in 1957. Clearly these years also covered both the world war and the raising of the Iron Curtain with the political and cultural dominance of the Soviet Union under Stalin’s baleful influence a powerful factor. The five works offered here as “world premiere commercial recordings” [the Overture however did appear on the Olympia label in a 1964 performance and the Symphonic Études appeared on a 1962 Polskie Nagrania Muza LP] all come from a small window of time between 1947 and 1952. This covers the height of the Stalinist terrors so the question must be whether the music was to some degree shaped by the imperative of appeasing the zealous apparatchiks of the Polish State.

The results are – on the evidence of this disc alone – works of moderate scale with the six movement Symphonic Etudes the longest running to a compact and concentrated 17:56. Overt emotion is kept in close control often replaced by either a muscular dynamic restlessness or neo-classical lyricism. The Mountaineers Triptych and the Popular Suite both suggest the influence of Soviet Realism and the need to embrace elements of folk and popular culture by appealing to ‘the masses’. Malawski orchestrates effectively although not that individually as is evidenced in the slightly unrelenting Overture that opens the disc. This is 7:37 of kinetically propulsive music that would benefit from greater dynamic and expressive contrasts. Richard Whitehouse in his useful but concise liner does not elaborate on the context of the work or its conception – indeed none of the works are ‘explained’ in terms of the source of inspiration, celebration or commission. One feature that does recur in several of the works offered here is an ending which Whitehouse, referring to the Overture, describes as “summarily curtailed”.

Here and throughout the disc the playing of the Artur Malawski Podkarpacka Philharmonic under conductor Mariusz Smolij is very good technically and musically committed. Smolij acts as the disc’s producer too and my one criticism is that the recording, while detailed, is a little close. The upside of this is that the complexity of the scores and the precision of the playing is effectively revealed, the downside is the reduction of the dynamic range and a reinforcing of the sense of relentlessness that I found ultimately fatiguing when listening to the disc in a single sitting.

There is far greater contrast to be found in the Etiudy symfoniczne (Symphonic Études) for piano and orchestra. The soloist here is Beata Bilińska and she is excellent. Her playing combines ideal clarity and brilliance with a sense of cool control and poise. Again the actual recording minimises the dynamic range and the piano used has a hint of brittleness that I think is an artefact of the engineering rather than a reflection of the playing. The same could be said of the strings of the orchestra who have a fraction of wiriness to their collective sound that is different from the bed of weighty string tone that has become the norm in recent years. That said, that sound does suit the music with more than a hint of a throw-back to recordings from the Eastern Bloc before the fall of the Soviet Union. The work itself is attractively concise and varied with each of the six contrasting movements played with little or no break. No.4 Notturno is both the longest section at 5:08 and the heart of the work. Here and in the preceding No.3 Toccata it seems to encapsulate the best of Malawski and the stylistic range of his music. This is the work that was performed abroad during his lifetime and is mentioned most often in any writings about the composer.

The following Tryptyk góralski (Mountaineers Triptych) is a work that does not survive complete and so is performed here in a 1988 completion by Kazimierz Wiłkomirski. Rather frustratingly the liner does not elaborate on the amount of work required to ‘complete’ the score or indeed what the original score represented. Rummaging online I found a quote – which I do not know is correct – on a music forum; “The piece is based on tuneful melodies of the Tatra/Podhale region – often employed by Polish composers, e.g. Paderewski (his Tatra Album for piano), Zelenski, Noskowski, Szymanowski, and recently Gorecki, Kilar..” This would make sense as in a couple of the scores offered here there is a feeling of ‘absorbed folk music’ where motifs and rhythms are repurposed in a contemporary idiom. Certainly in the Suite popularna that closes the disc there are moments reminiscent of the way Bartók mines Hungarian folk heritage in his music. As far as I can judge, Wiłkomirski’s completion sounds thoroughly idiomatic and effective and again receives an energetic and dynamic performance. Part of the online search revealed various versions of the work for solo piano but I have not made any comparisons.

Although not referring to this specific piece, Whitehouse comments on the “hectic or even brittle interplay” of Malawski’s writing and certainly that is a characteristic evident at points across all of these works. Where that is balanced by passages of calm and poise is when Malawski’s music is most effective. Such is the case in the Toccata for Small Orchestra. This Toccata runs for a very similar length to the previously mentioned Overture but the variety of style and chosen scale of the work impresses more than bombastic Overture. The orchestration is neo-classically light; just pairs of flutes, clarinets and trumpets alongside two percussion and a single trombone as well as the usual strings. The self-imposed textural restraint proves the old adage of “less-is-more”.

The disc is completed by the Suita popularna (Popular Suite). This is another compact collection of brief contrasting movements – here five totalling 15:15. Whitehouse points out that its 1952 composition date meant Malawski having to find an artistic accommodation where his personal style could be expressed in a manner acceptable to the political doctrines of the time. The result is by no means as “light” as comparable works by other Eastern Bloc composers sometimes are, but at the same time the level of compositional complexity compared to the Symphonic Études is deliberately less – this is consciously simpler music. Again the playing of the Artur Malawski Podkarpacka Philharmonic makes the best possible case for the score.

Possibly the interest in this music lies in how it places Malawski in the musical eco-system of Poland in the years immediately after World War II. The craft and care are never in doubt but on the evidence of this disc alone there is not the uniqueness of utterance and compelling expressive voice that marks out his close contemporaries. Take for example Grażyna Bacewicz – a composer whose star in recent years is very much in the ascendency. Interestingly Bacewicz was another violinist turned composer and just five years younger than Malawski. Recent multiple releases of a wide range of music have shown Bacewicz to have a genuinely distinctive and impressive ‘voice’ – something which Malawski, on the evidence of this single release, does not seem to match. Given the breadth of Malawski’s achievements in the cultural life of Poland as teacher, administrator, president of the Polish Society for Contemporary Music and other roles, it might well be there that his enduring legacy resides. This is a welcome and well-presented survey but it does not make me rush to hear more.

Nick Barnard

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.