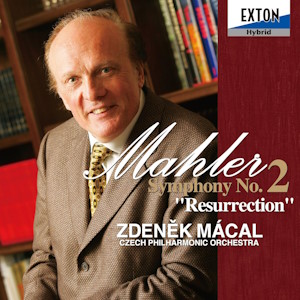

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Symphony No. 2 in C minor, “Resurrection” (1888-1894)

Renée Morloc (alto), Danielle Halbwachs (soprano)

Prague Philharmonic Choir Brno

Czech Philharmonic Orchestra/Zdeněk Mácal

rec. studio & live, 2008, Dvořák Hall, Rudolfinum, Prague, Czechia

Exton OVCL-00370 SACD [82]

The present recording is from a partial cycle that Mácal recorded with the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra on Exton in the 2000s. Although this series is relatively difficult and costly to obtain both in physical and digital formats, I do believe that this production is worthy of a review due to how well-balanced the interpretation is and how transparently the sound of the storied ensemble from Prague has been captured.

At a high level, Mácal’s conception of Mahler’s 2nd is quite moderate but detailed; tempi, textures, dynamics and timbres are neither taken to extremes nor underplayed. The Allegro maestoso (quickly, solemnly) is not pushed too hard, either, in terms of pacing or contrasts, and opens with just the right amount of zeal by the cellos and basses, even though the accelerandi in measure 4 (track 1, 0:11) have been omitted by the conductor, as they too often are in performances of this work. The tranquil second subject is shaped lyrically by the upper strings, though the tempo relationship is notably off in this double-exposition movement. Mácal actually adapts a considerably slower tempo for the first appearance of this theme (track 1, 2:41), marked Im Tempo nachgeben (in a relaxed pace) than the second (track 1, 6:06), marked sehr mässig und zurückhaltend (very moderate and held back), when it should be the other way around. This detail is important to realize because Mahler ramps up the expressive intensity of the two subjects as they progress through the movement’s structure. This is what critics often judge when they talk about whether an interpreter has a firm grasp of a work’s form or not. The development section fares extremely well, however, with the ferocious Vorwärts (forward) section starting at measure 196 (track 1, 10:13) bursting forth with crisp and taut articulation from the whole orchestra. Likewise, the next Schnell (fast) section with its jump-scare reprise of the opening theme (track 1, 11:50) does a tremendous job of showcasing both Mácal’s attention to the percussion parts and the lifelike sonics of Exton’s engineering. The Molto pesante (very heavily)climax of the development section, measure 325 (track 1, 15:34) is rendered brilliantly in both expression and technique. Conductors often either ignore or forget that Mahler only marked the ritardando (measure 328) at the very last bar before the massive unison octave drop (measure 329) and end up slowing down too much too soon. Not so here; Mácal starts applying the brakes at the second half of measure 328, and only lightly at that – to cataclysmic effect, as all the momentum of the immense build-up is preserved until the actual point of release. The rest of the first movement carries on very well indeed, with a tempo relationship neatly observed at the end: The sudden Tempo I (track 1, 22:23) of the descending chromatic scale is merely a return to the speed of the Nicht schleppen (not dragging)(track 1, 21:33)section from about twenty bars prior, instead of the much stormier Allegro maestoso at the top of the movement, just the way it should be. Bravo, maestro!

The Andante moderato flows along in a very gemächlich (comfortable) manner indeed. Each succeeding tempo change is rendered acutely here, with the glissandi in the strings beautifully realized. It is a pity that the intensified contrasting section (track 2, 4:41) abruptly takes off at a breakneck speed that is significantly brisker than what Mahler asked for, which is simply a return to the movement’s basic nicht eilen (not rushed) tempo. The real surge is supposed to launch a bar later (measure 133), which is actually marked energisch bewegt (energetic movement). Nitpicking, perhaps, but every tempo change is important to the expressive arc of this mammoth symphony, methinks. The last return to the opening theme (track 2, 7:15) is sensationally realized by the Czech Philharmonic here, with the timbre of the pizzicati strings registered in impressive realism.

Next, we have the Scherzo with its tricky sardonic, pungent expression. The main theme almost allows the Czech ensemble’s world-renowned woodwinds to be savoured by one instrument group at a time (track 3, 0:22), and I must say that the phrasing and articulation are executed at a remarkably high level here. Perhaps the single and double reeds alike could be brought forward a tad more to allow for further spotlighting, but I find Exton’s realistic presentation of the soundstage to be commendable as well. The “cry of despair” at measure 465 (track 3, 7:47) could have used considerably more power since it’s marked fff and then sempre fff by the composer after all, though I do appreciate the fact that Mácal did not hold back the tempo here superfluously, as some conductors cannot resist doing.

Morloc’s singing in the Urlicht (primal light) movement is gorgeous–what a silky smooth legato voice! Mácal and the Czech Philharmonic provide a suitably ethereal accompaniment to this heavenly song, with the etwas bewegter (somewhat more movement) middle section (track 4, 2:34) serving as a contrasting episode of heightened expression.

While the finale’s initial outburst is somewhat muted in grandeur, it is incredibly detailed like the whole recording in general. The low tam-tam stroke (track 5, 0:01) has such an epic, captivating resonance to it that it is a real shame that it fails to return in full splendour at the culmination of the symphony. The first appearance of offstage brass (track 5, 1:43) has the horns accurately placed in the background, with the brass chorale’s Dies Irae theme (track 5, 6:21) beautifully played and blended across the choir. The prematurely triumphant section that ensues has the horns blazing in glory like it should; however, Mácal curiously did not hold back the tempo even though the wieder breit (again, broadly) indication empowers him to do so (track 5, 7:32). The enormous percussion crescendi that begins the “march of the dead” section (track 5, 9:18) are stunningly well-executed, with the increases in volume perfectly graded, and the tension released properly at the apexes of each buildup not just once, but both times. The allegro energico (quickly, energetically) episode that follows is very well-paced (track 5, 9:35), as there is sometimes a risk of losing traction here. Unfortunately, the climax of the march where the escalated Dies Irae theme returns in the trumpets and trombones (track 5, 12:09) is too subdued, once again seemingly a conscious decision of the conductor, the engineers, or both. The grosse Appell (“great call”) has all instruments involved captured in marvelous detail, though Trumpet 1 from the offstage band is not at all placed aus weiter Ferne (from a far distance) and immer fern und ferner (always far and farther) compared to the rest of its group like measure 452 and 468-471 require (track 5, 17:08, 18:20-18:51). The choir’s first entrance at measure 472 (track 5, 18:55) is plenty misterioso (mysteriously) indeed, though. In general, I think the softer end of the dynamic range is rendered more effectively throughout this recording compared to the louder, with low level details almost always reproduced more satisfyingly. The “O, glaube” (“O, believe”) section is sung beautifully by both Morloc and Halbwachs (track 5, 25:40), and both vocalists are spotlit in the foreground. The “bereite dich!” (“prepare yourself!”) exclamation at measure 633 (track 5, 28:27) that ushers in one of the greatest buildups in the symphonic repertoire is rather timid, since it should be a sudden awakeningfrom ppp to ff. Thankfully, the ensuing climax fares better with significantly more presence from the entire orchestra and chorus at the glorious arrival of the final “Aufersteh’n” (“Rise again”) verse, measure 712 (track 5, 30:58). The organ is also full-bodied here, unlike in some versions, even otherwise highly accomplished ones, like Boulez’s with the Wiener Philharmoniker (review here). The magnificent closing pages often prove challenging to recordings of this symphony, as the battery of percussion, organ and rest of the gargantuan orchestra must almost always compete for the musicians and audio engineers’ limited bandwidth. Here, the organ and tiefe glocken (deep bells, as specified by the composer) take up the foreground at the expense of the high and low tam-tams and most everything else, even the roaring six trumpets and four trombones are placed midground at best. Topping off the eighty-two-minute performance is a resplendent E-flat major chord in the entire orchestra that is ripped away by Mácal in only a quasi scharf abreissen (sharply broken off) manner at best, but at least it does not commit one of my greatest pet peeves in all of Mahler’s oeuvre, when conductors needlessly elongate the final sonority, presumably to lend it more fullness.

Under Zdeněk Mácal’s direction, the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra sounds wonderful throughout this recording of one of Mahler’s greatest works. Ultimately, this is a splendidly recorded, detailed production of Mahler’s 2nd, though one that is relatively moderate in both expressive and sonic presentation. In my opinion, this release would be of high interest to those who prefer a temperate, balanced approach to this symphony, as well as to enthusiasts of the legendary Czech ensemble. For other listeners, there are numerous options that might serve them better, as this has rightfully been one of the most popular symphonies in the catalogue for quite a while. The Czech Philharmonic’s own recent version with Semyon Bychkov on Pentatone (reviews here, here and here) is just one of many recommendable alternatives.

Kelvin Chan

Availability: CDJapan