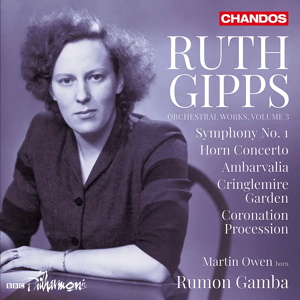

Ruth Gipps (1921-1999)

Orchestral Works Volume 3

Coronation Procession, Op 41 (1953)

Ambarvalia. A Dance Op 70 (1988)

Concerto for Horn and Orchestra, Op 58 (1968)

Cringlemire Garden. An impression for string orchestra, Op 39 (1952)

Symphony No 1 in F minor, Op 22 (1942)

Martin Owen (horn), BBC Philharmonic / Rumon Gamba

rec. 2022, MediaCityUK, Salford, Manchester, UK

Chandos CHAN20284 [75]

Another volume in the ongoing survey of the orchestral music of Ruth Gipps from Chandos gives us a further opportunity to get to know her music, this time in five works that span the whole of her creative life.

Gipps was born into a musical and financially secure family and became a prodigy at a tender age. She enrolled at the Royal College of Music aged 16 to study piano, oboe and composition. She had some impressive teachers (and fellow students) but to my ears she was most influenced by Gordon Jacob, a similarly undervalued composer today. When war was declared, Gipps was at Durham studying but her CV soon attracted the City of Birmingham Orchestra who offered her a place playing oboe and cor anglais.

Her first piece that made people sit up and take notice was Knight in Armour which featured on volume 1 of this series (vol. 2). That work first performed by the RCM orchestra under Gordon Jacob was taken up and given the following year (1942) at the Proms by Sir Henry Wood. It was at this time that Gipps completed her First Symphony. The BBC Philharmonic under Rumon Gamba here present its debut recording.

Dedicated to George Weldon (who was soon thereafter to be appointed Principal Conductor of the CBO) it is a substantial and ambitious work of 37 minutes’ duration. From the very beginning, you may pick up some influences: Tippett’s A Child of our Time in those opening brass chords, Vaughan Williams’ Job, Bliss’ Music for Strings. Picking out reference points is not an exact science but Gipps would have been aware of and receptive to the music she heard and played at the time, I am sure. The first movement has plenty of ideas and interesting thematic material. I am not wholly convinced what she does with it all is completely successful; the movement seems not to drive in any specific direction and for me betrays a lack of experience with the longer symphonic form.

The pastoral mood of the slow movement is much more notable. Elegy-like, the theme first heard on oboe is passed between sections and embellished with tenderness (e.g. track 8 at 2:08). The mood darkens and passions rise but we are soon calmed again by the reassuring gentleness of this haunting theme, this time on the cor anglais and finally taken up by the first and second violins (from 5:57). It is an enthrallingly beautiful movement.

The third movement is a pretty tame scherzo and trio featuring top billing for cor anglais and the Symphony ends with a finale in a similar vein to the opening. Themes are once again varied and seem to come and go in episodes that I find a little nebulous. The march-like tread just dies out at the end and I am left wondering what might have been. The Symphony had to wait until 1945 for its first performance. At this concert, presumably at the Town Hall in Birmingham with George Weldon conducting the CBO, we get from Ruth Gipps’ correspondence a little insight into the politics and unpleasantness that can sometimes occur in any large organisation. Undoubtedly there was some prejudice against her from some in the orchestra. She was still in her early 20s and as a successful woman with good contacts she seems to have rubbed some people up the wrong way. In the same concert she had not only played in the orchestra (remember those oboe and cor anglais solos) but also had been the soloist in the first half performance of Glazunov’s Piano Concerto No.1. Perhaps some in the band resented her having so much of the spotlight. There are always two sides to these things, though; certainly later that year she left the orchestra to return to London.

One aside to this: Weldon and Leslie Heward before him leading the CBO, left us some 78s from the war years. I wonder if Ruth Gipps played on any of those recordings?

I hear a lot of the influence of Arthur Bliss in Gipps’ music and I am sure his return to England from America during the war meant a lot to her. Bliss became the Director of Music for the BBC in 1942 for a short time. He was also one of the composers to have their music played for the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in June 1953 (along with Bax and, famously, Walton). Gipps also wrote a piece she named Coronation Procession but it was shelved. Its recorded premiere here shows it to be a striking work. As you would expect, we have fanfares but there is also a charming innocence and an air of well-being. Maybe Gipps was heralding this new Elizabethan age and emphasising the feminine touch as much as the pomp and circumstance. This performance from the BBC Philharmonic and Gamba is excellent.

Cringlemire is an arts and crafts house with views across Lake Windermere. It once had a thriving Thomas Mawson garden, now mostly overgrown. Gipps’ eponymous piece for strings, written about movingly here dates from 1952 and is worth hearing, with its echoes of the Vaughan Williams Tallis Fantasia.

The Horn Concerto of 1968 is a super work. It has been recorded at least twice before. The version on Lyrita with David Pyatt also includes concerti by Gordon Jacob, Malcolm Arnold and York Bowen. This version features Martin Owen, principal horn with the BBC Symphony Orchestra. At just 17 minutes in duration the piece fits a lot in and is a technical challenge for the soloist with virtuosic leaps, double tonguing and plenty of material in the instrument’s upper and lower registers. The performance is flawless and I hope will ensure the work gets played a little more often. All three of its movements are little gems but my favourite is the wonderful finale with its variety, rhythm and infectious zest for life.

The 1960s should have been Ruth Gipps’ glory years. She was in her prime as a composer but her works lay for the most part unperformed. The reason for some of that neglect may lie with the BBC and Proms Controller William Glock. Now, I have a lot of respect for Glock; a favourite pupil of Artur Schnabel he did a great deal of good at the BBC and the Proms raising standards and sweeping away bad habits. He introduced foreign orchestras and opera to the Proms, he put early music on the airwaves and you have to respect anyone who was sacked by The Observer for writing too much about Bartók despite warnings! Glock by all accounts, though, was often a barrier to those British composers still wedded to traditional tonalities and forms, and their music often remained underplayed and undervalued. This is a real shame and it affected many more composers than just Gipps.

One practical thing Gipps did was to set up orchestras on her own initiative to provide opportunities for amateurs and semi-professionals to play and for composers to have their works heard. Of course, in those days the Arts Council and the LCC were led by visionaries who made sure the funding was there. The London Repertoire Orchestra she set up in 1955 was essentially a night-school class, it still exists today. (website)

This new CD ends with a piece Gipps wrote in 1988 called Ambarvalia. It is a short memorial to a friend and is a delightful little movement that sounds folk-song based with graceful tunes and novel use of a celesta. What a lovely way to end the record. The notes tell us it is another premiere recording. I’m afraid not: Somm recorded it in 2019 on their disc devoted to Piano Concerti of Dora Bright and Ruth Gipps. Still, it is great to hear it here.

There is plenty more music by this excellent composer. Maybe we will get the aforementioned Piano Concerto in the next volume with the last Symphony (No. 5). I want to finish by paying tribute to the BBC Philharmonic, Rumon Gamba and Chandos for recording this music. They continue to build up a huge and ever impressive discography of consistently high quality. Gamba himself has already amassed a legacy of British music on record that can be spoken of in the same terms as that of Martyn Brabbins, Gavin Sutherland, John Wilson and Martin Yates. These great artists and others I could name are worthy successors to legends like Venon Handley and Richard Hickox and other venerable names from the LP era and earlier. Long may their success on record continue.

Philip Harrison

Previous review: John Quinn (January 2025)

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.