Déjà Review: this review was first published in December 2002 and the recording is still available.

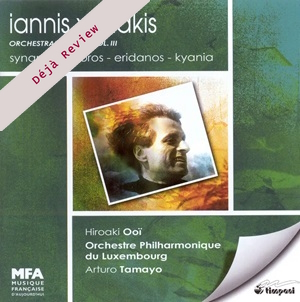

Iannis Xenakis (1922-2001)

Works for Large Orchestra, Vol 3

Synaphaï, for Piano and Orchestra (1969)

Horos (1986)

Eridanos (1972)

Kyania (1990)

Hiroaki Ooï (piano)

Luxembourg Philharmonic Orchestra/Arturo Tamayo

rec. 2002, Conservatoire de Musique de la Ville de Luxembourg. DDD

Timpani 1C1068 [64]

Anyone who read my reviews of the earlier volumes in this series will know how highly I rated them. They will certainly feature in my discs of the year. This important series continues with this latest disc, an intelligently planned mixture of works from thirty years of the composer’s creative maturity.

For many, the item of most interest will be Synaphaï, a concentrated work for piano and orchestra that is effectively Xenakis’s first concerto. The composer, as one would expect, re-interprets what we expect to hear in a work for soloist and orchestra. The work is in one movement, but three clearly defined parts. The pianist’s role varies, from playing within the various sections of the orchestra to being pitted against it, as in a conventional concerto. Xenakis, rather like Bartók, exploits the percussive nature of the piano; thus, we get extremely rapid note repetitions contrasting with dense clusters. The pianist is sometimes required to play ten staves simultaneously, with up to sixteen melodic lines within those staves. The composer wisely takes the precaution of stating in the score’s preface, ‘The pianist plays all the lines if he can’. Well, the formidable difficulties appear to pose no problem for Japanese virtuoso Hiroaki Ooï, whose fingers of steel make light of a piece he has come to be associated with. The characteristic ‘cloud’ textures of the orchestra, with massed strings and wind creating shifting patterns, gives the work a dialectic nature, as if a cat-and-mouse game is being played out with the piano. The first big climactic outburst (track 1 – 3:50) subsides and the protagonists pick themselves up for another go. The whole piece is immensely imposing, though less so on disc than in the concert hall, where Xenakis’s imaginative experiment with groupings (the orchestra is divided into four ‘columns’ across the stage) create a bold and imaginative spatialisation effect, akin to Stockhausen. Nevertheless, this is a superb achievement, the glorious acoustic and well-placed microphones helping the aural experience.

Horos opens with a terrifying impact. In most of his works for large orchestral forces, Xenakis delights in superimposing large blocks of sound, then almost mathematically alternating and varying the interplay of these blocks. Horos illustrates this to perfection. He is sometimes strict in his rhythmic and melodic notation, at other times giving freedom to the performers, and between these extremes is played out a web of sonority that is constantly moving, almost malleable. The emerging blend of timbres takes us from something soothing to something cataclysmic in a very short time span, so be warned, it is not a comfortable listen.

Xenakis once stated, ‘For me, sound is a sort of fluid in time’. Kyania is a piece where the chaotic turbulence of natural events seems to find a musical counterpart. Some of the sections in this piece are borrowed from Horos, giving the two works a tenuous but valid link. There is certainly an underlying seismic activity within the orchestra that is not dissimilar. One feels, as in The Rite of Spring, that elemental, volcanic forces are at work. The orchestra rages and howls, and one can look for clues in these cries of despair to other, non-scientific areas of the composer’s background. He once tellingly wrote of his wartime years: ‘In my music there is all the anguish of my youth, of the anti-Fascist resistance and the aesthetic problems they posed, together with the gigantic street demonstrations or the rarefied mysterious noises, the mortal noises of the cold nights in December 1944 in Athens. Out of this was born my interest in masses of sound’. This may help the listener come to terms with some violently disturbing but compulsively hypnotic sound-worlds created in these works.

By contrast, Eridanos sounds like an attempt at an ‘easier’ aural experience, though very much in the Xenakis mould. There is almost a hint of a melody (dare I say it, the ‘Holly and the Ivy’?, track 3 – 2:13), though it is fleeting and almost certainly unintentional, albeit a nice speculation. This is another of Xenakis’s works where orchestral contrasts, this time between strings and brass, are systematically played out. There is dialogue then opposition, interplay then violent clash. However, the effect is easier on the ear (at least for those not accustomed to the harsh sonorities of this composer) and the wondrous variety of string texture, where every conceivable device (pizzicato, glissando, ponticello, tremolo) is employed and superimposed, is challenging and rewarding. The title of the piece references the disturbed, deep-eddying River Eridanos of mythology. Apparently, it also has roots in the Greek word eristikós, meaning quarrelsome; and that is an apt description for what the composer does with his orchestral groups.

As before, this is an important release. We are able to build up a fascinating picture of a composer who had an extraordinary capacity for renewing himself, technically as a musician and philosophically as an artist. One can detect the constants that characterise him, and are the hallmark of a great composer. One can also hear the torment, the contradictory side of the creative impulse.

Liner notes, by Makis Solomos, are authoritative and readable (complete with referenced footnotes). Performances are equally authoritative, and the sound quality serves the artists superbly. This is a must for enthusiasts of the composer, who will no doubt be collecting this series anyway, as well as anyone with the remotest interest in music of the post-war years. Timpani are to be congratulated.

Tony Haywood

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI and helps us keep free access to the site