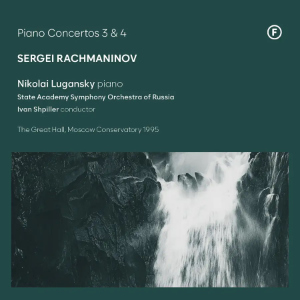

Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943)

Piano Concerto No. 3 in D minor, Op. 30 (1909)

Piano Concerto No. 4 in G minor, Op. 40 (1926 rev. 1941)

Nikolai Lugansky (piano)

State Academy Symphony Orchestra of Russia/Ivan Shpiller

rec.1995, Great Hall, Moscow Conservatory

Fineline FL72418 [70]

Difficult to understand though it is today, neither of these concertos was well received by its first audiences. No. 3 has gone on to be one of the most popular of all piano concertos. No. 4, on the other hand, is far less frequently played. Rachmaninov subjected the work to extensive revision, most of which involved cuts. Nikolai Lugansky, as is now common practice, plays the work in its final revised form of 1941. The two works are vastly different. From its opening theme, given out by the soloist in unadorned octaves, the D minor concerto is a succession of richly scored, long-breathed romantic melodies. It is also stupendously challenging technically. The G minor, on the other hand, makes fewer demands of the soloist – though the finale, in particular, is no pushover – and the orchestration is much more transparent and restrained. A further major difference is that in place of extended melodic writing the composer employed much figuration and fragments of themes. Most listeners will not miss these melodies, however, especially in the first movement which is a miracle of how to compose an extended passage of music with the minimum of material. Much the same can be said of the finale, the movement that suffered most from Rachmaninov’s scissors. The main theme of the slow second movement is rather unpromising, though, and there is some weight in the argument that says that Rachmaninov insists on it to the extent that content is spread rather thinly. None the less, though it will probably never rival the third concerto in popularity – even less so the second – it is a satisfying work whose sound, though pared down and less romantic, is unmistakeably that of its composer.

Nikolai Lugansky was in his early twenties when he recorded these performances, and his reputation was still to be firmly established outside Russia. They first appeared on the Vanguard label, but have also been available in other guises, including compendium issues from Brilliant Classics. Ten years after recording these works Lugansky returned to them again, setting down all four Rachmaninov concertos with Sakari Oramo and the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra for Warner Classics. I have not heard those performances, but find it hard to imagine that they are superior to these, at least in respect of the soloist. The third concerto receives a stunning performance here. Listening while following the score one is struck, first of all, by the horrifying number of notes and wonder how any pianist could ever learn to play the work at all, let alone from memory. Lugansky yields to no one in respect of the work’s stupendous technical demands, but just as striking is the sheer beauty of tone he produces throughout the dynamic spectrum. The work is full of sudden contrasts and changing moods. The lyrical second section of the first movement, for instance, is extremely poetic in Lugansky’s hands, yet he switches on the passion, even violence, with ease elsewhere. Also evident from the score is how faithfully these performers respect the composer’s markings. Where Rachmaninov wants the music to move on, but stipulates ‘a little’, that is precisely what these performers do, and, as often as not, from exactly the point the score demands it. There is less variation of pulse and phrasing, less overt expressiveness, in this performance than one often hears, and some might find the playing a little straight or lacking in character. I would not share that view. On the contrary, I find that the soloist’s approach produces a reading of great integrity, where respect for the composer’s intentions is more important than the soloist’s own portrait.

Similar observations can be made in respect of the performance of the fourth concerto, whilst adding that there is even greater mercurial variety of mood and expression in that work than in the third. Lugansky is masterly, feather-light where required, yet when fortissimo playing is called for he treats us to playing of powerful refinement rather than blunt force. There is great rapport between Lugansky and Shpiller in both concertos, and the orchestra plays extremely well. It may not possess the last ounce of polish, and the horns tell you straight away that you are listening to a Russian ensemble. Textures are clear, both from the orchestra and from the soloist, and when Lugansky finds himself accompanying orchestral soloists he does so with great sensitivity. The recording is perfectly fine, and the balance between the piano and the orchestra is ideal, a particular pleasure.

The booklet carries a photo of Lugansky alongside an interesting essay by Ronald Vermeulen (translated by John Lydon) that concentrates on the history of the two works, their composition and early performances, and which also introduces us to a conductor called Eugene Normandy. The finale of each concerto follows the second movement without a break, as the scores demand. However, the same thing happens between the two concertos, so that the opening notes of No. 4 follow instantly after the rousing close of No. 3. If you cannot programme your player this is a most regrettable production fault.

A vast choice exists of recordings of these works. Argerich live with Chailly on Philips in No. 3 and Michelangeli in No. 4 are classic choices, but I won’t be parting with Janis/Doráti (No. 3, Mercury) nor with Zoltán Kocsis/Edo de Waart (No. 4, Philips). I also have profound admiration for Leif Ove Andsnes with Antonio Pappano in all four concertos on Warner Classics. But I have been mightily impressed by these two performances from the young Lugansky and will certainly come back to them when I want to hear these works in the future.

William Hedley

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free