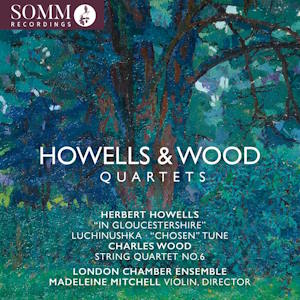

Herbert Howells (1892-1983)

‘In Gloucestershire’ (earlier version, 1920)

From Three Pieces for violin and piano, Op 28 Nos 2 and 3 (1917)

Charles Wood (1866-1926)

String Quartet No 6 in D (1915-16)

London Chamber Ensemble Quartet

rec. 2023 (‘In Gloucestershire’ and No 2 of Three Pieces) and 2024 (Wood and No 3 of Three Pieces), The Menuhin Hall, Stoke d’Abernon, UK

SOMM Recordings CD0692 [61]

The history of the disappearance, reappearance, revision, loss and reconstruction of Herbert Howells’ ‘In Gloucestershire’ string quartet almost rivals, in complexity, the plot of a baroque opera – the synopses of which always defeat me before I’ve even read two lines. So, I had to re-read the booklet notes several times before I could fathom what had happened to the quartet’s various iterations and which particular version is presented in this new recording. Even now, I’m not wholly sure I have it right.

I’ll try to keep things simple and short. Howells wrote a quartet in 1916 which was then almost immediately lost in a train. He rewrote it in 1919 with new material. After private performances, this version too disappeared. Before it disappeared, though, Howells replaced three of the movements, with only the Scherzo remaining largely intact. This is the version that’s usually played. However, in the 1980s a set of parts from 1920 was discovered and therefore it’s this ‘earlier’ version, newly reconstructed, that is recorded here. It’s been edited by Jonathan Clinch and Joseph Spooner, the cellist of the London Chamber Ensemble Quartet. An error in the track information dates the quartet to 1923 but I have been assured that this will be corrected to 1920 when the disc is reprinted.

This version of the quartet is gracious, mellifluous and attractive. The second subject of the first movement has a kind of half-veiled quality that is both like Vaughan Williams and yet also independent of his influence, though it shares a similar air. The flickering, brief Scherzo – the one consistent movement in the absurd history of the work – resounds with pizzicati and prepares the listener for the slow movement. The rarefied lyricism is conspicuous here, with very free espressivo writing, beautifully sustained, and genuinely consoling in mood. The finale embraces folklore with a vengeance – a crisp and frolicsome movement based on a folk dance, employing frisky pizzicati and drone effects to advantage.

Madeleine Mitchell has arranged two of the Three Pieces for violin and piano, Op 28 for string quartet. So she and the group – Gordon McKay, violin, and Bridget Carey, viola, in addition to Mitchell herself and Spooner – play No 2 ‘Chosen Tune’ and No 3 Luchinushka. The latter is a rather Russian-sounding folk tune and No 2 is Howells’ ‘Elgarian’ piece. Given the greater density of sound of a quartet arrangement you might think the performances would be a touch slower than the originals but in fact, no. Paul Barritt and Catherine Edwards recorded the three originals back in 1993 for Hyperion and they take the same timings – though both relevant pieces are, it’s true, small in size.

The other quartet is Charles Wood’s Quartet No 6 in D, composed in 1915-16. In his book ‘The Music of Charles Wood’, Ian Copley remarked that ‘no quartet of Wood’s can surpass it in the superbly polished workmanship that went into its construction’. Words such as ‘polished’ and ‘workmanship’ make me worry because they make me suspect that I will hear ‘humdrum’ and ‘correct’ music-making.

In fact, Wood’s is a delightful work – open-hearted, generous-minded and thoroughly old-fashioned, not that anyone should worry about that. Its opening generates a welcome drive and there’s vigour a-plenty as well as an easy, generous warmth and an Irish folklike theme. This element continues in the Scherzo which is a Reel, laced with pizzicati and a contrasting lyric theme, and the slow movement is a set of variations, the construction and contrasting of which Wood was adept. So it is here with intimacy, lyric moments and stern unisons. Ernest Walker, composer and writer, reckoned that the coda to this movement was one of Wood’s greatest compositional achievements. There’s a full outpouring of Irishry in the finale – a folk dance of unbridled exuberance, textually related to the first movement and bringing to an end a most attractive work. There’s no indication that his last completed quartet was ever performed during his lifetime.

The Wood will appeal to British Music admirers, as it’s a premiere recording, whilst the Howells will leave them with a dilemma – how many versions of his quartet do you need? Given, however, that they are both different versions of ‘In Gloucestershire’ a strong case can be made for wanting them both, not least in such commanding, finely recorded and eloquent performances as these.

Jonathan Woolf

Previous review: Nick Barnard (October 2024)

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI and helps us keep free access to the site