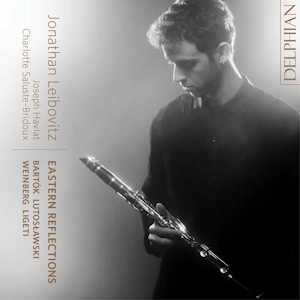

Eastern Reflections

Jonathan Leibovitz (clarinet)

Charlotte Saluste-Bridoux (violin)

Joseph Havlat (piano)

rec. 2023, St. Mary’s Parish Church, Haddington, UK

Delphian DCD34319 [57]

This is a concept album, featuring music by composers who were all under political pressure in the middle years of the last century. The works involve violin, clarinet and piano, mostly in pairs, but featuring one work for all three, which is Bartók’s Contrasts. The players here all come from the Young Classical Artists Trust (YCAT), which has made a number of recordings with Delphian.

Contrasts was commissioned in 1938 by the clarinettist Benny Goodman, a jazz player who occasionally played classical works. At the time, Bartók was realising that the European situation was such that he would need to emigrate. Goodman hoped that the work would fit on the two sides of a 78rpm gramophone record. Bartók originally planned a work in two movements, Verbunkos (Recruiting Dance) and Sebes (Fast Dance), which derived from the lassú and friss of the csárdás. However, he then added a middle movement, Pihenõ (Rest), which owes nothing to folk music, but is a version of the night music which he uses in other works.

I must admit that I have tended to think Contrasts the least interesting of Bartók’s chamber works, and far inferior to the violin sonatas or the quartets. Still, nothing by Bartók is negligible, so I was willing to give it a chance. I was very agreeably surprised to find that I greatly enjoyed this performance, much more than I have others I have heard in the past. The clarinettist, Jonathan Leibovitz, has a delicious nutty tone and all the virtuosity you can want, as well as really getting into the spirit of the folk idiom. He has a big cadenza in the Verbunkos, which he despatches with aplomb. The same can be said for the violinist, Charlotte Saluste-Bridoux, who gets her cadenza in the Sebes. The pianist, Joseph Havlat, provides good support, but is not given much chance to shine in this work.

There are two other big works here, as well as three little ones. Lutosławski’s Dance Preludes were written in 1954 and were the last of his works to derive from folk music. At the time, he, like most Eastern Europeans, was living under a Communist regime which required artists to practise socialist realism, which meant writing easily accessible works which would appeal at least to party apparatchiks though notionally to ordinary people. Works based on folk music tended to win approval. Lutosławski’s work was originally written, as heard here, for clarinet and piano, though he later produced not one but two enlarged versions, one for clarinet and orchestra and another for nine instruments. These pieces draw on folk music but are also studies in rhythms, with different rhythms superimposed upon one another. They are charming pieces which have become well established in the repertoire.

The other big work is Weinberg’s sonata for clarinet and piano. Weinberg wrote this in 1945, by which time he had left his native Poland to settle in Moscow and was leading a relatively normal life, despite being under Stalin’s rule and having come under suspicion for promoting Jewish culture. Weinberg was attracted by the clarinet, for which he also wrote a concerto and a solo role in his Chamber Symphony. This sonata is a light-hearted and optimistic one, in three movements. It opens with a solo clarinet line before the piano joins in and the mood darkens somewhat. The middle movement shows the influence of klezmer. The weight of the work is in the finale, marked Adagio, which moves through a succession of moods and eventually fades away. It contains a cadenza for the clarinet.

We also have three smaller works. The two by Ligeti are student works, which have been rearranged here. A bujdosó (The Errant One) is one of a set of songs, here arranged for clarinet and piano. Baladă şi joc (Ballad and Dance) was a piece for two violins – Ligeti possibly had Bartók’s duets for two violins in mind – and is here performed by clarinet and violin, thereby giving Charlotte Saluste-Bridoux a second opportunity to shine. Both are based on folk music: Ligeti was under the same pressure as Lutosławski.

Finally, we have an arrangement of one of Shostakovich’s Op. 34 piano Preludes. Shostakovich championed Weinberg, to the extent of successfully defending him in a letter to the chief of the secret police when he had been arrested. This Prelude dates from about ten years earlier and is a kind of waltz gone wrong.

Here we have three substantial works and three miniatures, making up a very satisfying programme. The playing is as accomplished as one could wish, the recording is excellent and this is altogether a successful recital.

Stephen Barber

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free

Contents

Béla Bartók (1881-1945)

Contrasts, for violin, clarinet and piano (1938)

György Ligeti (1923-2006)

A bujdosó (1952, arr. for clarinet and piano)

Witold Lutosławski (1913-1994)

Dance Preludes, for clarinet and piano (1954)

György Ligeti

Baladă şi joc (1950, arr. for clarinet and piano)

Mieczysław Weinberg (1919-1996)

Sonata for Clarinet and Piano, Op. 28

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Prelude No. 17 in A Flat, Op. 34 (1932-3, arr. for clarinet and piano)