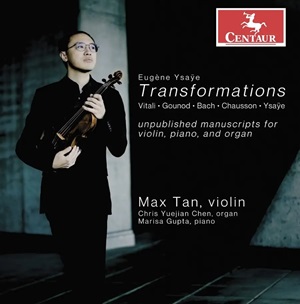

Eugène Ysaÿe: Transformations

Tomaso Vitali (1663-1745)

Chaconne (arr. Eugène Ysaÿe)

Charles Gounod (1818-1893)

Méditation sur le Prémier Prélude de Piano de J.S. Bach (arr. Eugène Ysaÿe)

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Violin Concerto No 2 in E major, BWV 1042 (arr. Eugène Ysaÿe)

Ernest Chausson (1855-1899)

Poème, Op 25 (arr. Eugène Ysaÿe)

Eugene Ysaÿe (1858-1931)

Andante, Op. post.

Max Tan (violin)

Marisa Gupta (piano)

Chris Yuejian Chen (organ)

rec. 2021, Troy National Savings Bank, Troy, NY, USA

Reviewed as a download from Naxos Music Library

Centaur CRC 4129 [54]

With “Transformations” as the theme of this new disc from Centaur, gifted American violinist Max Tan explores unusual transcriptions for violin, organ, and piano by the Belgian violinist and composer Eugène Ysaÿe. Famous for his colourful temperament and energetic playing, the larger-than-life Ysaÿe is mostly recalled today as the dedicatee of a number of significant violin works, including the sonatas of César Franck and Guillaume Lekeu and the Chausson Poème. (For a lovely thumbnail portrait of Ysaÿe as a violinist and teacher, read Nathan Milstein’s autobiography From Russia to the West.) Ysaÿe’s own compositions have fared less well than the Franck or Chausson; many violinists over the past century have attempted to shoehorn Ysaÿe’s six solo sonatas into the canonical repertoire, but the public has stoutly resisted. The violinist’s more palatable works such as the Chant d’hiver or Poème élégiaque go mostly unperformed.

This disc is the result of a conversation between Tan, pianist Marisa Gupta, and violinist Philippe Graffin. Gupta and Graffin made their own recording of some of Ysaÿe’s unpublished manuscripts [review by Michael Cookson] and that collaboration seems to have spurred further exploration by Tan. He was encouraged by long-time Juilliard administrator Jane Gottlieb to look through the Ysaÿe archives in the Juilliard Library. The manuscripts recorded here by Tan are visible to the public via a Juilliard library link.

The album kicks off with Ysaÿe’s elaboration of the familiar Vitali Chaconne arranged for violin and organ. One is immediately struck by Ysaÿe’s subtle realization of the organ part and by the violin part itself. It is much more imaginative than the busy-but-dull Charlier version dutifully performed by a generation of French violinists, and less bombastic than the transcription by Auer beloved of Heifetz and his imitators. Ysaÿe writes counterpoint for the organist that is convincingly Baroque in quality yet contains just enough harmonic and rhythmic spice to catch the ear. The latter half of the piece is significantly different from the “standard” versions. Overall, Ysaÿe’s vision of the Chaconne is more dignified than that of Charlier or Auer, with much less emphasis on virtuoso fireworks. The only false note comes in the brief coda, when the violin part becomes overwrought and the formerly understated organ part bloats into a Victorian monstrosity representative of the French organ school at its worst.

This aural equivalent of a Zeppelin hoving into view is quickly followed by a saccharine but thankfully subdued transcription of the Bach/Gounod Prelude in C major (aka the Ave Maria, for you Mario Lanza lovers). I expected the violin to burst out into double-stops a la the Schubert-Wilhelmj “Ave Maria,” but it never happened. Ysaÿe inserts a repeat (double the fun!), presumably to give both piano and organ a chance to shine. (The first “stanza” is taken by the violin and piano, and the organ joins in the second time around.) Of note on this track is the purity of Tan’s intonation, his warm sound, and his intelligent use of portamenti.

From this point onwards, the album takes a bizarre turn. We are treated to a transcription of the Bach Concerto No 2 in E major, with the violin part appearing as expected (though not without some anachronistic ornaments courtesy M. Ysaÿe) but the accompaniment being arranged for piano and organ. The effect is a bit like how Percy Grainger might have “dished up” the piece for his beloved harmonium. Is it bad? No. Does it really need to exist? Probably not. Tan and Lev Mamuya give a spirited defense of the art of the transcription in the booklet notes, attacking fuddie-duddies who have “…been trained to, perhaps superficially, associate an often literal compliance with the composer’s score with spiritual reverence for the music.” I agree that transcription (or even significant editorial tinkering) is a valid art form that deserves to be taken seriously as a means of artistic expression. The question that doesn’t appear to have been asked here is, what does the transcription add to the music that was not already there? Does the orchestral part in this new piano/organ guise lead to any new understanding of or appreciation for the score? Ysaÿe’s well-known re-working of the Saint-Saëns Étude en forme de valse is an example of a transcription that has moved beyond the boundaries of the original. The violinist takes a solo piano show-piece and repurposes it in virtuoso fashion for violin and piano. It is extremely effective as a concert work, being decked out by Ysaÿe with all sorts of violin-specific acrobatics.

Returning to this disc; adding an organ part to the concerto piano accompaniment doesn’t elevate Bach’s music, and it may even detract from the score in a way that having a straight piano accompaniment does not. (The sound of the piano and organ combined does not gel at all, in some places creating an undefined, fuzzy tonal quality that weakens Bach’s crisp textures.) That being said, it is intriguing to hear this arrangement at least once to experience how an important early 20th-century violinist viewed the score. The performance itself is energetic and tasteful. Gupta handles the awkward piano reduction in the Allegro movements with great sophistication and seeming ease.

I will admit that I felt a bit uneasy when I heard the opening chords of Chausson’s mega-erotic Poème squeezed out by the chaste, thin-toned organ. Tan and his collaborators heroically do their best to sell this transcription, playing with real guts in the climaxes. However, listening to Ysaÿe’s reduction is like watching a particularly severe pen-and-ink artist create a tiny black-and-white line drawing based on a sumptuous, epic oil painting. The massive emotions of the original disappear, and what remains is the hollow sound of numerous piano tremolos underpinned by the wheezy organ. Again, this is no indictment of the playing of Tan, Gupta, and Chen. Gupta does her best to give heft to the piano part, but even Horowitz and Virgil Fox brought back to life could do little with this arrangement. Ysaÿe’s small alterations to the violin part are mostly unremarkable, except for one short bridge passage that does work slightly better than the Chausson original.

The final work on the album is Ysaÿe’s Andante for violin and piano. This piece goes down easy, being a typical late-Romantic Gallic confection that could have been written by any period violinist-composer worth his salt, but it doesn’t leave much of an impression.

The value of this recording is ultimately found in the excellent performances given by Tan and his colleagues. The violinist plays with rock-solid intonation and impressive overall technical command. Just as importantly, he plays with a true sense of the style in which these pieces were originally performed. He varies his vibrato throughout and does not shy away from applying the abundant slides that one can hear in Ysaÿe’s own recordings. To Tan’s great credit, his portamenti possess the unique vocal quality found in the recordings of “golden age” violinists; this is a sound that many modern violinists are unable to recreate. I hope that Tan and Gupta will return to French repertoire, perhaps exploring the significant body of violin/piano pieces written for Ysaÿe that have not been over-performed. Composers who wrote sonatas for the Belgian include Dubois, Jongen, Magnard, Ropartz, Samazeuilh, and Vierne. It is also time for a modern recording of Charles Martin Loeffler’s Partita, which was last recorded in 1935 by the American violinist Jacques Gordon and pianist Lee Pattison. I look forward to Max Tan’s next release!

Richard Masters

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI and helps us keep free access to the site