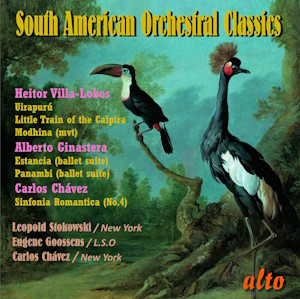

South American Orchestral Gems

New York Stadium Orchestra/Leopold Stokowski (Uirapurú, Modinha)

London Symphony Orchestra/Eugene Goossens (The Little Train, Suites)

New York Stadium Orchestra/Carlos Chávez (Symphony)

No recording information provided

Alto ALC1497 [73]

Much as I might lament the low appreciation and availability of Latin-American music today, things were considerably worse in the 1970s. If a composer was represented at all, it was often by a single piece or handful at best, and then in a limited number of performances. Such was the case when I first discovered Alberto Ginastera and wanted to hear his music. The only practically available version was an Everest LP played by the London Symphony Orchestra under Sir Eugene Goossens. The issue in the mid-1970s in the UK was that the LP vinyl pressings of Everest disc were absolutely dreadful; if it did not pop or click, it was warped and distorted. But through that snowstorm of hi-fi mediocrity some actually rather compelling performances appeared.

Fast forward to the advent of CD. As with several labels where poor LP transfers compromised originally fine engineering, the Everest back catalogue has emerged somewhat battered by the LP experience but now able to display the quality that was always present. For this disc, Alto have delved into the Everest catalogue and built an interesting programme around the complete LSO/Goossen disc bookended by performances by the “Stadium Symphony Orchestra of New York” – or the New York Philharmonic moonlighting if you prefer.

The release makes no reference to its Everest origins but they are worth considering. The Wikipedia article here makes interesting and worthwhile reading. In essence, Everest was founded in the late 1950s to make the finest possible stereo recordings of unfamiliar/unrecorded repertoire performed by top conductors and orchestras, and on several occasions the composers themselves. For their recordings, they had built 35mm magnetic film recorders using just three channels. This was very similar to the process which RCA “Living Stereo” applied at the same time to great effect, but lasted less than a decade. In the CD era, the original Everest recordings have reappeared in various guises: straight LP re-releases, some with the short LP playing times, some with new re-couplings, 20-bit “35 mm Ultra-analog” – and now these licenced reissues. What remains true whatever version, coupling or guise these performances have, they are remarkably fine technically and musically for recordings nearly seventy years old.

This collection begins with Leopold Stokowski conducting the moonlighting New Yorkers in 1958 in two Heitor Villa-Lobos scores: Uirapurú and the Modinha movement from the Bachianas Brasileiras No.1. (The original coupling, rather unusually, was a suite from Prokofiev’s Cinderella.) The musical and technical qualities are genuinely very fine. Musically this is right up Stokowski’s street: he revels in the lush orchestral colour, the sensuous harmonies and the wealth of texture and incident. No real surprise, then, that this is a musical triumph, only how well the three-channel recording captures the detail and originality of the scoring is. The stereo spread is extremely effective, the complex percussion writing is caught very very well.

Recordings in the 1950s, even by top companies and engineers, struggled with percussion transients with cymbals and timpani, let alone any Latin American instruments all too often muffled or lacking crisp ringing brilliance. That is all here. Perhaps the front to back orchestral picture is not as deep as we might expect today, and just occasionally at the biggest climaxes the sound is slightly flattened and a little congested. This is a hard and – one assumes – unfamiliar score. I doubt the hard-working New Yorkers were doing this as anything except a read/record session. If that was the case, they play very well indeed. Once or twice the upper strings in alt are just a little scraggy but the conviction of Stokowski’s reading carries the day comparing favourably, if it does not top more recent versions for urgency and engagement. The “but” is that Stokowski cuts around four minutes and more from the score. As a ‘library’ performance for all its virtues, I do want to hear it as the composer intended. For me, that relegates this version to the status of fine historical reference.

Modinha finds Stokowski in his absolute element. He wrings every ounce of romantic melancholy out of this movement for an “orchestra of cellos”. The score requires “at least eight cellos”. I have no idea how many are here but it surely is substantially more than eight. Also, the ebb and flow and handling of every phrase make this far more a Romantic work than a Bachian one. Other versions can sound rather chaste next to this. I love it, although I can imagine some would find it too gushing. That said, playing and engineering are again first rate for its date.

Everest used a mobile version of their 35mm system when recording abroad. When one directly compares the New York sessions to the London ones with the LSO, it must be said the USA sessions have a degree of extra clarity and precision, although the LSO sessions remain very fine. I have the Vanguard “20 bit” version of this Goossens recording (although with some George Antheil in place of the Stokowski and Chávez). Direct comparison reveals little if any difference. There is no indication which masters Alto have used but they sound essentially identical to this earlier ‘premium’ release, so they are very good.

Eugene Goossens was one of those ferociously multi-talented musicians who are all but forgotten today. In his lifetime, his career was blighted by a scandal that would barely make a ripple in the news cycle today. When he died in 1962, it was just too early for him to have made a substantial contribution to the recording industry with discs that technically might endure today. But he was an important and fine conductor. Amongst other things, he conducted the UK premiere in 1921 of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring.During World War Two, he commissioned various composers, one of whom was Copland with the Fanfare for the Common Man. Right at the end of Goossens’s life, he made a series of recordings for Everest with the LSO. That included, amongst others, a Rite and a Petrushka,genuinely an exciting and impressive listen today.

As I noted, the original Everest LP was my introduction to all three works, so I have very fond memories of them. Trying to remain objective, I must say I was pleased with how well they stand up both as performances and as recordings. Again the engineering, for late 1950s, is excellent. It is perhaps just a tiny bit less detailed than in New York but still clear and detailed. Percussion and orchestral writing like piano and harp are impressively clear and present. Notable too is Goossens’s sensible and appropriate choice of tempi in both Ginastera’s suites and Villa-Lobos’s pieces. Nothing swaps speed for energy or impact. The Little Train rattles across its Prairie in a charmingly characterful and colourful way – this was for so long one of the Villa-Lobos “pops” that I am not sure why it does not seem to feature nearly as much in programmes any more.

Likewise, the two ballet suites by the young Ginastera – his “cowboy” ballet Estancia,and the native Indian myth of Panambi – are very well-represented by the two standard four-movement suites. In recent years, complete versions of the ballet are far more common. Still, has to be said that these two suites still contain the essence of each work in a way that will satisfy many listeners. The machismo of Estancia is very well realised, and the LSO play with dynamic energy what must surely have been unknown music. (That said, one of the horns entertainingly goes crashing through a phrase end, repeating a figuration when everyone else has correctly stopped. That is the 3rd movement, The Cattlemen, track 6, 1:25.) This four-movement suite may easily be Ginastera’s most played, best known work. There are versions with even greater impact: the early DG recording by Gustavo Dudamel and his astonishing Simon Bolivar Youth Orchestra of Venezuela does take some beating! So this group of recordings are, for me, good but not the absolute top choices. One mayfind it worth considering given the label’s mid-price good value.

The last item may increase that sense of “worth considering”. Carlos Chávez conducted the New York Moonlight Players in his own Symphony No.4 Sinfonia Romantica.The original Everest LP included generously his Symphonies No.1 Antigona and No.2 India. Sinfonia Romantica had a world premiere recording here. Chávez was a good conductor and the orchestra genuinely fine, so the stature and significance of these recordings have endured, and lifted them out the simply archival interest category. There have been many recordings of these symphonies since, some again very fine.

Hopping back from the London sessions to New York, the ear again registers the audio benefits of Everest’s “main” recording set-up. The sheer quality of the technical aspect of the production is very impressive. Compared to the complete survey of Chavéz’s six symphonies by Eduardo Mata and the LSO, Chávez conducting Chávez is so much more vibrant. (That said, Mata also recorded some Chávez in Venezuela, with seemingly greater engagement.) Again, there is an occasional momentary feeling of ensemble and intonational issues for the upper strings, but the sweep and drive of the performance marginalises these concerns.

The three-movement Sinfonia Romantica is less instantly nationalistic than any of the other music offered here. In that sense, the Symphony No.2 India might have been a more logical if less generous coupling. Overall this is quite an abstract, not really romantic work. Even so, according to the liner notes quoting the Louisville premiere, “the composer’s descriptive title points up the lyric and emotional character of the work as a whole”. Again I was struck how effectively the engineering here resolves the complexity and detail of Chávez’s scoring. Some of the instruments are so present that I find it hard to believe that more multi-miking than just three channels was not involved. Whatever the technical truth, the result is immediate, engaging and impressive. The bustling closing Finale – Vivo non troppo mosso is the section where echoes of Latin American rhythms and instruments fleetingly appear.

Overall, this is a well-produced, well remastered selection of three classic Everest discs ( although nowhere on this reissue is the original label mentioned, just BMG as the current holders of the rights to the Everest catalogue). All of the music included here deserves to be better known and more often heard. If this interesting compilation achieves that, then it has done its job well. Alto are very astute at trawling the back catalogue such as Koch, Classico and Unicorn, amongst other defunct labels. It must be hoped that there will be further fruits from the Everest archives.

Nick Barnard

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free

Contents

Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887-1959)

Uirapurú (1917, rev. 1948)

Modinha (Bachianas Brasileiras No.1) (1930)

The Little Train of the Caipira (Bachianas Brasileiras No.2) (1931)

Alberto Ginastera (1916-1983)

Suite from Estancia (1941)

Suite from Panambi (1940)

Carlos Chávez (1899-1978)

Symphony No.4 Sinfonia Romantica (1953)