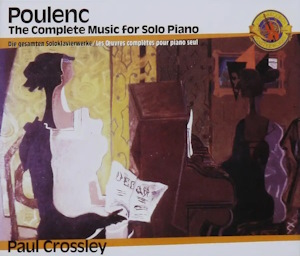

Francis Poulenc (1899-1963)

The Complete Solo Piano Music

Paul Crossley (piano)

rec. 1987-89, Snape Maltings, Suffolk, UK

Presto CD

Sony Classical M3K44921 [3 CDs: 133]

I have had a lovely time listening to these discs. Poulenc’s music is so fascinating and so multi-faceted; one moment he’ll produce a phrase with harmonies of such haunting beauty they’ll summon forth tears, the next something so disarmingly silly that it makes you laugh out loud. Of course, he wrote in so many genres and for so many instrumental and vocal combinations; but the piano occupied a central place in his musical life, and a collection such as this by Paul Crossley, spanning forty-five years, three discs and well over two hours’ worth of music, creates a satisfying picture of his kaleidoscopic musical personality.

Crossley and his collaborators clearly took great care with the curation of this collection. The order is by no means chronological; larger-scale pieces, such as the Soirées de Nazelles or the Thème varié are interspersed with smaller, lighter groups, or individual pieces. And there’s the delight of happening across something you don’t know – I knew, to my shame, only one of the gorgeous Nocturnes.

These recordings go all the way back to the late 80s, although the recorded sound is more than acceptable to ‘modern’ ears. But what about Crossley as a Poulenc interpreter? When this set was first published, there was surprise and a little consternation; Crossley was seen as a champion of avant-garde and ‘progressive’ composers, Messiaen in particular. It is well documented that Poulenc had made appreciative noises about the music of Messiaen (and even of his young ‘disciple’ Boulez). But was that admiration, however muted, ever reciprocated? Not to my knowledge.

Would Crossley, then, be able to find the pulse of Poulenc’s oeuvre? The staggering technique necessary for mastering Messiaen would mean that Poulenc would present few problems of that kind. It was more a matter of style, of empathy, with an ability to enter into Poulenc’s very particular, quirky world.

Well, not everyone has been convinced; but to my mind, Crossley is, and was, such a consummate musician and performer that he was able to find the ‘sweet spot’ in almost all these pieces. Yes, he is inclined to use more ‘rubato’ – subtle expressive changes of tempo – than Poulenc himself prescribed. One of the most beautiful, and famous pieces in the collection is the first of the three ‘Novelettes’, composed in 1927. Here Crossley, for me, bends the music too much. Other pieces suffer somewhat from this tendency, such as the ‘Pastourelle’ and the Valse-Improvisation on B-A-C-H. Compare him with Pascal Rogé, who, in his complete set for Decca of 2011, is more detached, with the result that the lovely melodic lines of the Novelette are clearer, and make their point without any need for interpretative ‘intervention’.

But in other places, Crossley’s feelings for texture and balance bring magical results. The third of the eight ‘Nocturnes’ is called ‘Les cloches de Malines’ – ‘The Bells of Malines’ – and is inspired by the poem of that name by the American Henry van Dyke. ‘Malines’ is a Belgian town, now known as Mechelen, which suffered horrifically in WW1, and the poem is a moving and powerful one. Crossley perfectly captures the impassivity of the bell-tones that persist through the piece, and contrasts that chillingly with the brief but violent outburst in the central part of the piece.

Eric Parkin, another wonderful English pianist (though from Herts rather than Yorks) began his complete set of recordings around the same time as Crossley, though Parkin’s second and third volumes took many years to be published. (I have to declare an interest here, because Eric and I were colleagues for a number of years, and good friends too). He was best known for his great interest in the music of John Ireland; and in point of fact, there’s no great gulf between Ireland and Poulenc. Parkins’ readings are always affectionate and stylish; though he perhaps lacked Crossley’s sense of drama, so that the explosive middle part of ‘Les cloches de Malines’ is relatively under-characterised. But I for one certainly wouldn’t wish to be without the Parkin recordings, partly for personal reasons, but also because he was such a deeply sensitive performer. One drawback that has to be mentioned is that the perspective of the piano sound varies quite a lot as the discs progress – perhaps inevitable when you consider the long period over which the recordings were made.

As you might expect – to return to Crossley – he employs the piano’s percussive side delightfully to create the rustic humour of, for example the ‘Bourée au Pavillon d’Auvergne’, while he executes with stunning panache the dry staccato writing in pieces such as the Toccata of the ‘Trois Pièces’.

First impressions, though, are always important (even if sometimes misleading), which is why it was such a good idea to begin the whole set with Crossley’s masterly reading of ‘Les soirées de Nazelles’, a suite of eight variations enclosed by a ‘Préambule’ and a ‘Final’. Poulenc intended these, a little after the example of Elgar’s ‘Enigma Variations’, as musical portraits of his friends, who would join him for country evenings at his house in Noizay in the Indre-et-Loire. Roger Nicholls, always so perceptive where French music is concerned, describes the Soirées as ‘…the fusion of eclectic ideas in a glow of friendship and nostalgia’ (though, entirely inexplicably, Poulenc himself professed to loathe the piece!).

So, is this set THE one to buy for your complete Poulenc piano repertoire? Well, it is undoubtedly one of them! Crossley’s playing is of the highest musical, technical and imaginative quality. But the competition, though not large in number, is severe, and you might be swayed by what is missing, that is to say works in which the piano is of vital importance, but which are not strictly solo piano music. These include not only the chamber pieces with piano, but also the concertos, plus a marvellous piece like ‘Aubade’ – which in any case is effectively a concerto. All these you can find included in the set by Eric Le Sage on RCA Victor, and very fine it is; but honestly, why not have both Le Sage and Crossley on your shelves? I would – indeed, I have!

Gwyn Parry-Jones

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free

Contents

Les soirées de Nazelles for Piano (1930-1936)

Trois pièces (1917-1928, rev. 1953)

Mouvements perpétuels (1918, rev. 1939-1962)

Mélancolie (1940)

Napoli (1922-25}

Feuillets d’album (1933)

Pastourelle (1927)

Bourée au Pavillon d’Auvergne (1937)

Valse en ut (1919)

Pièce brève (1929)

Improvisations (1932-39)

Thème variè (1951)

Trois Intermezzi (1934 -43)

Cinq Impromptus (1920-21)

Presto en bemol (1934)

Badinage (1934)

Humoresque (1934)

Valse-improvisation (sur le nom de Bach)

Huit Nocturnes (1929-1938)

Suite Française (1935)

Trois Novelettes (1927-1959)

Suite en ut (1920)

Villageoises (Petites pieces enfantines) (1933)

Française (d’après Claude Gervaise) (1939)

Promenades (1921)