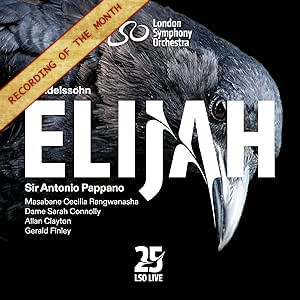

Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847)

Elijah, Op 70, MWV A25 (1856-46)

Masabane Cecilia Rangwanasha (soprano), Dame Sarah Connolly (mezzo-soprano), Allan Clayton (tenor), Gerald Finley (bass), Ewan Christian (treble)

London Symphony Chorus, The Guildhall Singers

London Symphony Orchestra/Sir Antonio Pappano

rec. live, 28 & 31 January, 2024, Barbican Hall, London

Text included

LSO Live LSO0898 SACD [2 discs: 121]

This recording of Elijah has been issued just as Sir Antonio Pappano commences his role as Chief Conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra at the start of the 2024/25 season. Actually, there’s been a bit of a run-in period after the departure of his predecessor, Sir Simon Rattle and the concerts from which this recording derives were part of that transition. Pappano’s tenure has begun auspiciously: he led a very fine account of War Requiem at the Proms, which I very much admired when watching on TV, and the opening concerts of the 2024/25 season at the Barbican have been enthusiastically reviewed in the media.

The first of the two performances from which this new recording was compiled was reviewed for Seen and Heard by my colleague, John Rhodes. I saw his enthusiastic appraisal at the time and noted that the performance had been recorded for LSO Live. John’s review whetted my appetite for the recording and now, issued with commendable speed some eight months later, here it is.

Before I discuss the performance, it may be appropriate just to say a word or two about the text that is sung. Those who are familiar with the work will notice a lot of changes to the commonly used libretto. The booklet tells us that we are hearing the German libretto in the “English translation by William Bartholomew, with amendments”. Whose amendments have been adopted is not revealed. Some of the changes seem to me to be desirable: for example, in the closing chorus of Part 1, “Thanks be to God, he reviveth the thirsty land” is preferable to Bartholomew’s “Thanks be to God, he laveth the thirsty land”. However, in the preceding exchanges between Elijah and the Child quite a lot of the prophet’s words have been changed in a way that seems to serve no great purpose. And in the tenor’s final aria I can’t see that “Thunder and joy shall be for everlasting” is an advance on “Joy on their heads shall be for everlasting”; the change seems fussy. Anyway, be warned that you may not quite hear the expected words during this performance and the changes are noticeable because all the diction, both from the soloists and the choir, is exemplary.

For the best part of a century after it was unveiled at the 1846 Birmingham Festival, Elijah was a staple of the British choral society repertoire; it was trotted out with a frequency exceeded only by Messiah. Unfortunately, I’m sure that this led to over-exposure and both choirs and conductors became too comfortable with the work. In recent decades, however, the stature of the oratorio has been rediscovered and in large part this has been due to performances and recordings that have demonstrated its dramatic nature. In his booklet note Michael White refers to Mendelssohn as “a conservative figure: decent, upright, with a settled domesticity in contrast to that of the bohemian Romantics from whose outlook and output he stood apart”. That’s a very fair assessment; Mendelssohn was poles apart from the likes of Berlioz and Liszt. Nonetheless, in Elijah, he gave us a work that, in the right hands, is full of drama and dynamism – think, for example, of the fiery chorus music after the Queen has turned the crowd against Elijah (‘Woe to him’). In recent years recordings led by conductors like Philippe Herreweghe, Paul Daniel and Paul McCreesh have really brought out the drama in the score. Moreover, the standard of amateur choirs is now such that they can do justice to such a view of the work. Sir Antonio Pappano is clearly one of those conductors who relishes the dramatic aspect of Mendelssohn’s masterpiece and in the London Symphony Chorus – and his soloists – he has just the singers to make the most of the opportunities that the score presents. With one or two small exceptions, I think he paces the score expertly. Where it makes sense to do so, he takes the recitatives quite briskly, which emphasises the natural speech rhythms; that’s not to say, though, that he doesn’t also allow for expressiveness in the recits when that’s appropriate. I don’t think it’s any coincidence that this performance is conducted by someone with extensive operatic credentials; it shows in Pappano’s intelligent and vital projection of the music.

Pappano’s approach is evident from the start in the way he conducts the Overture. The pace is urgent – though not pressed excessively – and what is striking is the wiry tone of the strings who seem to be playing with little vibrato. This imparts a lean character to the music, which in itself is welcome and allows good cut-through for the woodwind when they start to play. I very much approve of the tension that’s established early on in the oratorio; clearly, there’s going to be no Victorian stuffiness in this performance. Throughout the work the playing of the LSO is incisive and cultivated, as you’d expect from this world class ensemble.

The London Symphony Chorus is on terrific form. This is, I think, the first recording by them that I’ve heard since Simon Halsey retired as Chorus director. For this performance they’ve been prepared by his successor, the Argentinian conductor, Mariana Rosas. I noticed from her biography that when she came to the UK in 2018 to further her career she studied with Halsey at the University of Birmingham. If this present performance typifies her approach, then I think we can be confident that the very high standards which Halsey achieved with the LSC will be maintained seamlessly. I followed the performance in my vocal score and can attest that such things as dynamics are scrupulously observed. This attention to detail is by no means pedantic; on the contrary, it brings Mendelssohn’s music vividly to life. As a small example, early in Part 1 there’s a duet for the two female soloists which includes little chorus interjections (‘Lord, bow thine ear to our prayer’). Each of these is sung on one note – the pitch varies – and it can sound dull; but if the choir observes all the dynamics, as happens here, the music is anything but dull. Later in Part 1, when Elijah is challenging the power of the pagan god Baal the choir’s attention to detail demonstrates the changing mood of Baal’s followers: they start off confident that Baal will put Elijah firmly in his place but, as the episode unfolds, that confidence starts to drain away to be replaced by apprehension that Baal may not be as mighty as they believed. In Part 2 the choral singing is full of bite and electricity after the Queen has whipped them up against Elijah (‘Woe to him’). This is a thrilling chorus to sing and the LSC really delivers the goods. They’re equally successful in the less fiery numbers, such as ‘He watching over Israel’. Having sent Elijah up to heaven in his fiery chariot in an exciting fashion, the LSC then brings the work to a triumphant conclusion in the final chorus (‘Lord, our creator’). My only regret is that in the last 15 bars of the work, as the chorus sings ‘Amen’, Pappano follows the score and maintains a strict tempo. Many conductors allow themselves the luxury of a slight broadening of the tempo at this point to emphasise the grandeur; I wish Pappano had followed this unwritten tradition.

Before leaving the choral singing, I should mention that a small group of vocal students from the Guildhall School of Music and Drama participate in this performance as the Guildhall Singers. That’s as part of a collaboration between the Guildhall School and the LSO. Three of the singers, soprano Zoe Jackson and altos Alex Hutton and Abbie Ward sing the unaccompanied trio ‘Lift thein eyes’ in Part 2. They sing beautifully, though I wish Pappano had adopted a fractionally slower speed; the music seems a bit brisk, though that’s no fault of these gifted young singers.

Pappano has a stellar team of soloists. Before discussing the four principals, I must mention the treble soloist, Ewan Christian. Towards the end of Part 1, the character of The Child has a crucial part to play, looking out at Elijah’s behest for the slightest sign of a rain cloud. It’s a horribly exposed part but Ewan Christian is undaunted and sings his music clearly and confidently.

The soprano soloist is the South African Masabane Cecilia Rangwanasha. I well remember her making a tremendous impact at the 2021 BBC Cardiff Singer of the World competition (she won the Song Prize). Here, she impresses again. In her big Part 1 number (‘What have I to do with thee?’) she first conveys admirably the distress of the Widow whose son has died; then, when Elijah has restored him, she sings splendidly in her duet with the prophet. Her Part 2 solo, (Hear ye, Israel’) is, if anything, better still. Her singing is glorious. I love the combination of opulent tone and clarity of diction. Just as pleasing is the way in which she is clearly invested in the music. Dame Sarah Connolly makes a predictably distinguished contribution. She’s ideally expressive in ‘Woe unto them’ and brings consoling warmth of tone to ‘O rest in the Lord. In complete contrast, early in Part 2 she’s a vengeful, imperious Queen, trying to whip up the people – and succeeding – after Elijah has denounced Ahab (‘Have ye not heard’). Allan Clayton makes a fine showing as Elijah’s servant, Obadiah. Both of his arias are sung with clear ringing tone and an ideal level of expression. His recits are excellent too; his ultra-sensitive delivery of ‘See now, he sleepeth’ is a wonderfully poetic moment.

Of course, any performance of Eijah stands or falls by the performance of the title role. I’ve longed to hear Gerald Finley in this role; it was worth the wait. His commanding delivery of the introductory solo indicates that we’re in for something special; so it proves. Finley embraces every facet of Elijah’s character. When he confronts the adherents of the god Baal in Part 1, he is magisterially credible but the subsequent aria ‘Lord God of Abraham’ requires him to change tack and become dignified and humble; Finley achieves this with seeming ease. Moments later, he’s the avenging prophet (‘Is not his word like a fire?’). His rendition of this aria is a terrific exhibition of fiery, clearly articulated singing; Finley brings out all the drama – and he’s superbly supported by the orchestra. Then there’s compassion as Elijah pleads for an end to the drought which has afflicted the people. The Part 2 aria ‘It is enough’ is one of the peaks of the whole work. Finley rises to the occasion with an elevated piece of singing. The sheer sound of his voice is impressive but just as impressive is his identification with the character. Finally, ‘For the mountains shall depart’ is the dignified leave-taking that it should be. Finley is marvellous throughout.

Some years ago, I had the good fortune to take part in a masterclass in oratorio given by a very distinguished British singer. His advice to us was ‘tell the story’. When you listen to this performance I think you will feel as I do that all the performers – and I include the orchestra in this – have definitely told the story of the prophet Elijah and have done so in vivid terms. It’s a tremendous performance, one of the best I’ve heard on disc. If this is a harbinger of Antonio Pappano’s work with the LSO then there can be no doubt that the orchestra made the right choice of Chief Conductor. I look forward to more releases from the partnership on the LSO Live label. Recently, I’ve read an interview in which he suggests that a recorded cycle of the Vaughan Williams symphonies could be on the way. If that happens and future releases match the distinction of the pairing of symphonies Four and Six (review), then that will be a very appetising proposition.

LSO Live’s recording was made, as usual, by engineers from Classic Sound. They’ve done a fine job. I listened to the stereo layer of these SACDs and found that the sound had presence and excellent definition. Documentation is thorough.

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free