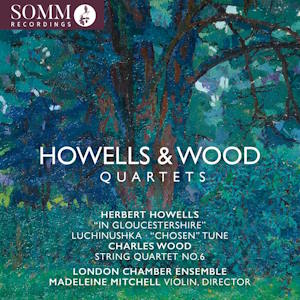

Herbert Howells (1892-1983)

String Quartet No 3 “In Gloucestershire” (earlier version, 1923)

Three Pieces for violin and piano, Op 28 (arr. string quartet, Madeleine Mitchell): No 3 Luchinushka; No 2 “Chosen” Tune

Charles Wood (1866-1926)

String Quartet No 6 in D (1915/1916)

The London Chamber Ensemble Quartet

rec. 2023/24, The Menuhin Hall, Stoke d’Abernon, England

SOMM Recordings SOMMCD0692 [62]

It would be something of an understatement to say that Herbert Howells was careless about the score of his String Quartet No.3. The work was first composed in 1916 and, as the liner notes put it, “was almost immediately lost”, apparently left on a train. Three years later, fragments of the original work started coming back to Howells, so he rewrote the piece. In effect, it was a recomposition. He completed the new version in 1920, at which point “this version also disappeared”, but it seems that this was more a withdrawal of a work than a loss.

Howells continued to work on the quartet and to revise it into the 1930s, to the point that only the 2nd-movement the scherzo remained essentially the same, albeit with a different title. This revision of the recomposed version is what collectors will know via other recordings, notably the Britten Quartet on EMI, the Dante Quartet on Naxos, and – the earliest of the three – Divertimenti on Hyperion.

The confusion arises from the retention of the title “In Gloucestershire” for basically quite different works. The London Chamber Ensemble Quartet led by Madeleine Mitchell are playing the earlier version – re-written, pre-revision – in a first recording. In some ways, I think Howells did himself a disservice with the title. It may lead the unconvinced to assume a cosy modal country idyll.

The liner notes quote the contemporary critic and musicologist Marion Scott. She said that Howells considered the work one of his best things, and it was “the real Gloucestershire”. What that means, I have no idea, unless some of the themes are transmutations of folk music. If they are, it is not all that obvious. The solo viola melody that opens the third-movement Andante assai espressivo has a distinctly ‘folkish’ feel, even when one realises that it is a reworked version of the second subject of the first movement. It is important to note that, unlike other Royal College of Music graduates, Howells did not actively use, let alone directly collect, folk music as a means to liberate himself from the chains of Austro-Germanic musical ideals. For him, the legacy of Renaissance and Elizabethan church music held that particular key. That in part explains his ecstatic reaction to hearing the first performance of Vaughan Williams’s Tallis Fantasia in Gloucester Cathedral in 1910.

The work performed here is substantial, as are all the performances regardless of version. This is a musically and harmonically ambiguous work, demanding at places. Too often, even listeners sympathetic to Howells’s music will consider it mainly from the perspective of what he produced after the tragic loss of his nine-year-old son Michael to polio in 1935. What Howells wrote immediately after his RMC studies is remarkably different: confident, complex and technically assured. By the time he came to do the first rewrite, he was just in this 30s. A divide is often made between the pupil-composers of Parry and Stanford at the RCM, and those at the RAM under Mackenzie and Macfarren. This score seems to straddle the two schools. The intense chromatic energy and high Romanticism of the RAM is fused with the formal clarity and craft of the RCM.

The London Chamber Ensemble Quartet give a good performance, full of dynamic brilliance and passion. I wonder if a little greater expressive freedom and sense of fantasy might have helped mitigate the rather unrelenting density of texture and musical thought. The youthful Howells is pretty unforgiving in his demands on all the players. It is only with extended familiarity that it is possible to relax into even the most complex passages.

As usual, SOMM’s engineering is reliably fine, and the dense scoring is clearly realised. The Menuhin Hall in Stoke d’Abernon has proved in the past to be a supportive but quite neutral space, and that suits this music well. The players could have been placed slightly further away from the microphones to let a little more air into the recording.

The liner notes, written jointly by Jonathan Clinch, Paul Andrews and Jeremy Dibble, suggest that this earlier version of the quartet is “tighter, more organic in its use of motives and full of nervous energy”. The later revision is “predominantly lyrical, expansive and rhapsodic”. Perhaps those descriptions are as much true of the composer as of the music. What the notes do not address is why Howells chose to revise this 1923 version so extensively. When he composed this version, his approach to quartet writing was quite different than that of his other two earlier essays in the form: Lady Audrey’s Suite Op.19 from 1915 and the Fantasy String Quartet Op.25 from a couple of years later. Both are very attractive, shorter and expressively smaller. This version of String Quartet No.3 “In Gloucestershire” seems to be pushing the boundaries of what Howells wished to achieve with the quartet format. Perhaps the later revision was intended to realign the work more in the spirit of the companion pieces.

Madeleine Mitchell’s arrangements of two of the Three Pieces for Violin and piano are closer to the spirit of the ‘gentler’ Howells than to the nervous energy of the quartet offered here. I do not know the violin and piano originals. No.2 Chosen Tune has been recorded quite often in its solo piano version. The version for quartet here sounds like a pretty straight transcription rather than arrangement of that. It is all the more effective for its simplicity. The arrangements are sympathetic, effective and well played. With that said, there are many original quartet scores from this period of English music still crying out for modern recordings. The inclusion of these arrangements instead seems like a programming opportunity missed.

For an example of the unexplored, under-appreciated riches of British chamber music from the first half of the 20th century look no further than Charles Wood’s String Quartet in D. It is a very interesting and intelligent coupling, especially since Wood was one of Howells’s teachers at the RCM. If we take Howells’s original composition from 1916 (albeit reconstructed in 1923), these are exactly contemporaneous works. Both have four movements, both last around the mark of mid-twenty-minutes.

The aspirational goals, on the other hand, seem vastly different. Howells shoots for the moon and on occasion arguably tries just too hard. In contrast, Wood’s piece feels more recreational: fluent, attractive, beautifully crafted and comfortable. Howells’s quartet is not a comfortable work but neither does it want to be.

Much like Howells, Wood may be remembered today, if at all, as a composer of Anglican church music. As a teacher, he joined Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, first as organ scholar and then as fellow in 1894. He became their first director of music and organist. After Stanford’s death in 1924, he became the titular Professor of Music for the whole University but, according to Edward J Dent, he had been fulfilling the practical teaching role in Stanford’s absence for some time before the official appointment. He died only two years after assuming the post.

Wood wrote some eight string quartets, only published in a memorial edition after his death. There is a sense that, much like another academician J B McEwen, Wood used the quartet form as a rewarding vehicle for musical expression without the pressure of large-scale commissions. The liner notes say that it is not clear if the work was performed during the composer’s lifetime, which again suggests that it was written as much for his own pleasure in creation as with any expectation of performance.

The famous handbook “The Well-Tempered String Quartet” references Wood’s quartet music thus: “every movement is distinguished by craftsmanship of the highest order. There is no striving for modernity…” Certainly there is a clarity and precision in the writing, and an awareness of the practical realities of string writing. That makes the music more immediately accessible to listeners and to players. Not that this is not demanding as well, but perhaps more forgiving. The counterargument is that the music is perhaps too comfortable. By not striving for more, it lacks the spark of individual genius that Howells has. But, as a work in its own right, this is very attractive. The London Chamber Ensemble Quartet give another fine and dedicated performance.

Wood was Irish by birth. This quartet is coloured throughout by themes of a distinctly Irish nature. The brief Wikipedia article references “the use of Irish folk melodies and dance tunes as thematic material”, and one of Wood’s quartet works is a Variations on an Irish Folk-Tune. Slightly frustratingly, it is not clear whether the thematic material in this quartet is wholly original or based on folk melodies. Ultimately this is irrelevant given the work’s instant appeal and warm-hearted good nature.

Perhaps it is control of the quartet texture where the more experienced Wood scores over the impetuous Howells. As I noted, Howells’s music can sound dense, even cluttered. Wood, while his music is often lush and sonorous, keeps the textures cleaner. He allows the listener to follow the musical argument even at first acquaintance. In some moments, I was reminded of Moeran’s String Quartet in E flat. It was published after Moeran’s death, but there is convincing evidence that he wrote the first movement around 1918, tantalisingly close to Wood’s piece. It also has passages which contain similar musical gestures, and the obvious shared Irish influence. There is no mention in the published literature, however, that Moeran had contact with Wood in any professional or teaching capacity. That said, Moeran attended the RCM in 1912 alongside Howells, Bliss and Benjamin, so there is an intriguing possibility that their paths crossed in some way.

This is not Wood’s first quartet to have received a fine modern recording. In a slightly unusual programme on ASV, replicating the first performance of Tippett’s String Quartet No.5, the Lindsay Quartet included Wood’s String Quartet in A minor alongside two of R.O. Morris’s Canzoni Ricertati – now that is a work which deserves a complete recording for starters. The parts for this D major quartet can be viewed on IMSLP here alongside three more of his quartets, but not the A minor quartet which the Lindsays played. Slightly frustratingly, the IMSLP single parts (no score included) are laid out in printing format, so are confusing to follow.

Overall, I found the performance of Wood’s piece more convincing than Howells’s. Still, that might be down to my own response to the more direct utterance of the music itself. The hope must be that this leads to recordings of Wood’s other quartets, although history shows that it is hard to generate sufficient interest in this music in terms of sales to warrant such an investment of time and money from artists or labels.

In the meantime, this is a valuable and illuminating recording of two substantial and fascinating works by composers at the opposite ends of their composing careers. SOMM have produced another impressive disc, less familiar music receiving committed performances, well-engineered. Both pieces deserve to be better known. One must hope that the London Chamber Ensemble Quartet have the opportunity to play these works more often and to discover, perform and record more of the hidden riches of this area of the repertoire. In the meantime, there is much to enjoy here.

Nick Barnard

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free