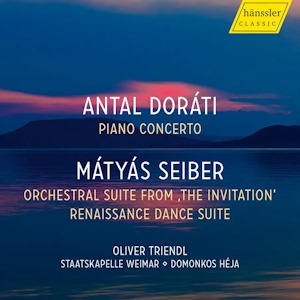

Antal Doráti (1906-1988)

Piano Concerto (1974)

Mátyás Seiber (1905-1960)

Orchestral Suite from The Invitation (1960)

Renaissance Dance Suite (1959)

Olivier Triendl (piano)

Staatskapelle Weimar/Domonkos Héja

rec. 2024, Orchesterprobensaal, Weimar, Germany

Hänssler Classic HC24035 [66]

It makes sense to have Antal Doráti and Mátyás Seiber appear together. They were contemporaries, studied at the Franz Liszt Music Academy in Budapest, and were pupils of Zoltán Kodály, who regarded them both highly. Their friendship lasted till Seiber’s untimely death in a car crash in South Africa. For information’s sake, Doráti’s Sinfonietta for String Orchestra is an arrangement of Seiber’s First String Quartet.

Doráti may be mainly remembered as a highly gifted conductor. He devoted much of his time to Haydn’s music, and to music by his fellow countrymen and his contemporaries. One tends to forget, however, that he was no mean composer either. I had never heard his music before, but while preparing this review I noticed that BIS has two discs with his music, symphonies on BIS-CD-408 and orchestral pieces on BIS-CD-1099 (review). Orfeo recently released his opera Der Künder (review). He wrote a cello concerto for Janos Starker, recorded by the dedicatee with the Louisville Orchestra and issued as an LP on the orchestra’s label.

Doráti composed the Piano Concerto for his wife, pianist Ilse von Alpenheim. They recorded it with the National Symphony Orchestra in Washington, DC. An LP was released on Turnabout.

The concerto is out in the traditional fast-slow-fast pattern. The first-movement Allegro moderato is rather animated and vigorous. About halfway in, the music calms down into a meditative, mysterious and at times anguished section, which leads into a cadenza of sorts capped by a final flourish. The second-movement Lento, rubato is a Nocturne in all but name, with a more animated central section. To my mind, it is the work’s finest movement. Bartók’s shadow and Doráti’s Hungarian musical roots loom large here, and over the concluding Presto.

Doráti’s Piano Concerto may not venture onto any new paths but it is quite beautiful and finely crafted. Oliver Triendl plays superbly. He must strongly believe in the music, and gets a committed support from the Staatskapelle Weimar and their conductor.

Seiber wrote The Invitation, his last piece, in close cooperation with choreographer Kenneth MacMillan. The action was largely inspired by La Casa del ángel by the Argentinian writer Beatriz Guido. We are told that the film version of the novel enjoyed great success around the world. (I have neither read the novel nor seen the film. The information on the ballet comes from Oliver Triendl’s detailed and informative notes.) Here are the rough outlines. A teenage girl and her cousin are at a party where they meet an elderly, disillusioned married couple. The Boy feels flattered by the advances of the older woman, whereas the Girl senses the sexual attraction that she exerts on the man until things lead to a brutal attack. Nothing particularly new here, although the overall theme points to a situation that – far from belonging to some fanciful past – still has striking relevance.

The score lasts almost an hour. Seiber and his Australian pupil Don Banks arranged the orchestral suite recorded here. The varied music reflects the action. The Introduction sounds rather ominous, while the ensuing Pastorale and Burlesque tend to dispel the impending gloom. The next movements are all fairly lighter in mood. The music alludes at times to the French Les Six – one may sometimes be reminded of Poulenc – and to Stravinsky, though Bartók is never far away. The music eschews any all-too-obvious eclecticism, because Seiber was a formidable composer in full command of his trade. As expected, the ballet does not end happily, so that the music eventually becomes dark and menacing. All in all, this is a gripping score in its own right, especially when played with such commitment and empathy as here.

The somewhat shorter Renaissance Dance Suite composed for the Croydon Symphony Orchestra is simpler and more straightforward. The three movements revisit tunes from the 16th century in delightful and colourful scoring. One may of course be forgiven for recalling Seiber’s own Besardo Suites or Respighi’s Antiche arie e danze. This delightful piece is a light-hearted conclusion to an enterprising release, worth exploring.

Hubert Culot

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free