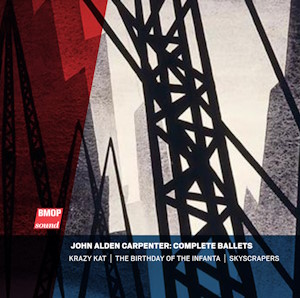

John Alden Carpenter (1876-1951)

Complete Ballets

Krazy Kat (1921, rev. 1940)

The Birthday of the Infanta (1917, rev. 1940)

Skyscrapers (1926)

Boston Modern Orchestra/Gil Rose

rec. 2019-21, Melrose Memorial Hall, Melrose; Jordan Hall, Boston; Mechanics Hall, Worcester, USA

BMOP Sound 1100 SACD [71]

The Chicago composer-businessman – and briefly, for three months, Elgar student – John Alden Carpenter was well placed to write his ‘Jazz Pantomime’ Krazy Kat in 1921. Not only was the city one of the hotbeds of Jazz but Carpenter also had a pithy grip on vernacular and on the cultural zeitgeist. The promotional material that comes with the disc talks of this particular comic strip featuring a ‘self-identified, non-binary character’ – well, did you evah! as Frank and Bing put it. And yet, putting that malarkey to one side, George Harriman’s Krazy Kat was a somewhat subversive comic strip with characters’ sexual identity remaining stubbornly unidentifiable. All very naughty for post-war Chicagoans, one supposes, if they even noticed.

The music of Krazy Kat is pertly orchestrated – in particular muted trumpet, trombone, the use of the alto saxophone, piano colour, and detailed winds – in support of the brief scenes depicted, which last in total about twelve minutes. ‘Krazy Kat Dances’ may not necessarily prefigure John Adams’s Dancing Chairman, but it exudes a joyful, openheartedness and romantic cleverness, too. Carpenter is good at syncopation, taut rhythms, cod-Spanish terpsichorean panels, and infiltrating bluesy cadences at the sprightly end of a piece which also illustrates his impressionistic inheritance. I don’t know what it is about this performance or the recording, but I found the percussion almost throughout exceptionally annoying and intrusive in the balance.

The Birthday of the Infanta, based on the Oscar Wilde short story, was composed earlier, in 1917, though, like Krazy Kat, it was to be revised in 1940. This ‘ballet pantomime’ is a much more extensive and seriously conceived work than its Jazz Pantomime sibling. It also features a wordless soprano soloist at various points though I can’t find her name listed in the documentation. Its story is of the Infanta’s birthday and the suicide of a court dwarf, Pedro. The costumes for the original production were based on those in Velázquez’ painting of the Spanish court Las Meninas, which is helpfully reproduced in colour in the booklet. There are numerous different versions of the score, but this recording uses the 1940 revised edition, in the composer’s hand.

The music is not only more serious it’s also more formal, evoking Spanish perfumery in a garden scene, and using percussion well. Romance is to the fore, as are serio-comic processionals with Stravinsky hints, elements that sound as if Falla wrote them (on a middling day, if we’re being honest), as well as strong Iberian punchy rhythms. There’s brassy vehemence and moments of compressed grandeur with fast-moving tableaux, colourful and vivacious. Pedro’s catastrophic moment of recognition, when he sees himself reflected in a mirror, duly deepens the expressive quotient of the score but only for a moment – before the slinky court resumes its self-absorbed and frivolous ways.

Carpenter’s ballet masterpiece has always been held to be Skyscrapers, ‘a Ballet of Modern American Life’ and indeed ‘Skyscraper Lullaby’ was the title of Howard Pollack’s biography of the composer. Carpenter was the only American composer to be asked by Diaghilev to write for his Ballets Russes, though in the end Skyscrapers was dropped and picked up by the Metropolitan instead. Composed in 1926, the composer wrote that the ballet had no plot, as such, but oscillated between the twin poles of ‘work’ and ‘play’, though there are three central characters – an entertainer, an ingenue and a street cleaner. This last role was taken by a black dancer and Carpenter used an all-Black choir, led by Frank Wilson, shortly to become the first Porgy in 1927.

Skyscrapers is a kind of study in rhythm allied to a conspectus of prevailing trends and currents in contemporary American music. It’s surely not coincidental that it seems to feed on the kind of music explored by Gershwin in Rhapsody in Blue (1924) and Milhaud in La Création du Monde (1923). Carpenter also infiltrated Stephen Foster into his score whilst generating chic velocity based on sassy jazz-derived models. The Chorus explores the Gospel-Jazz nexus and there’s a role for muted trumpet in the penultimate scene called ‘the Sandwich men’. For the last panel a biggish band swings brilliantly to conclude the work.

Carpenter’s belief that ballet was the form best suited to express modernity in music was an intriguing one, as it allowed choreography, orchestral music and a chorus – in Skyscrapers – to present a montage of contemporary life for the audience. Carpenter wrote much more than ballets, of course, as the Symphonies, Concertos, Sonatas, tone poems and other works illustrate but he was invariably au courrant in all he did. This snappy disc of his ballets is in the safe hands of Gil Rose and the Boston Modern Orchestra Project and the well-prepared performances – percussion in Krazy Kat to one side – is supported by first class booklet notes and recording quality.

Jonathan Woolf

Availability: BMOP