Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Concerto for Violin and Orchestra in D major, Op 77

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Partita for violin solo No 1 in B minor, BWV 1002: III Sarabande – Double

Carl Nielsen (1865-1931)

Symphony No 5, Op 50

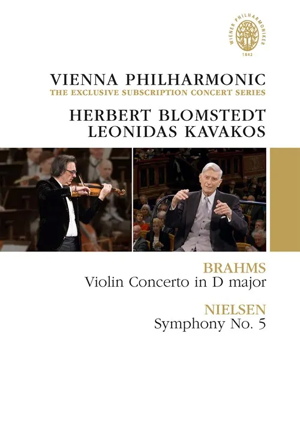

Leonidas Kavakos (violin), Weiner Philharmoniker / Herbert Blomstedt

rec. live, 2023, Goldener Saal der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, Vienna, Austria

C Major 766508 DVD [93]

This concert was filmed in 2023. Depending on when in the year the performances were given – the precise date is not supplied – Herbert Blomstedt would have been 95 or 96 (he was born on 11 July 1927). Inevitably, there’s evidence of some physical frailty; he takes the arm of an attendant to enter and leave the stage and he sits on a piano stool to conduct throughout the concert. His baton-less beat is tiny – but then he was never a flamboyant conductor- though he is clear in his physical gestures, especially during the symphony. Crucially, take a look at his eyes; there’s no indication of any diminution of alertness; clearly, all the work has been done in rehearsal and all he needs to do is to guide and finely shape the music as the performance unfolds.

The first work on the programme is the Brahms Violin Concerto with Leonidas Kavakos as soloist. The duration of the first movement is given as 24:38. Most of the performances in my collection clock in at between about 21 and 23 minutes long, but as I was going through the discs on my shelves to check this, I came across something of an outlier: a 2013 performance on Decca which involves the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig and Riccardo Chailly where the first movement plays for 23:41: the soloist is Kavakos. I’m sure that in both that recording and this present 2023 version the tempi will have been worked out jointly between conductor and soloist. Subsequently, I discovered a review by Simon Thompson of a 2019 performance in which Kavakos directs the performance as well as playing the solo part. I’ve not heard that but Simon refers to “speeds that are on the stately side”. It seems fairly clear, on this evidence, that Kavakos, the common factor, has a penchant for spaciousness in the first movement. I mention all this because though there’s much to admire – Kavakos plays beautifully and the Vienna Philharmonic supports him with distinction – the movement as a whole is, I’m afraid, far too leisurely. To be sure, there are passages where the energy inherent in the music is realised but overall, the spacious treatment of the music emphasises its ruminative poetry at the expense of vitality. In particular, the passage immediately following the cadenza is so broadly conceived that I thought it would never end. This comes as a serious disappointment since this is probably my favourite among all violin concertos and I love the wonderful first movement. On this occasion, I feel it falls flat.

Happily, matters improve thereafter. Kavakos’s playing in the glorious Adagio is simply ravishing – the purity of his tone is a constant delight – while the VPO accompanies him with burnished tones. The pacing is ideal. The finale is taken attacca. We experience an excellent performance that exhibits vitality and ample energy. It’s such a shame that the first movement is so drawn-out – though, of course, others may relish the spacious lyricism. As it is, I can only greet this performance with modified rapture.

As an encore Kavakos gives a very fine account of the ‘Sarabande – Double’ movement from Bach’s First Partita. This is a very shrewd choice after the revelry of the concerto’s finale and it’s remarkable how one man and a violin can hold a hall full of people in the palm of his hand.

I confess that the prime attraction of this release for me was the chance to see and hear Herbert Blomstedt conduct Nielsen’s Fifth symphony. It was largely through Blomstedt’s recordings – plus Jascha Horenstein’s account of the Fifth – that I first became properly aware of Nielsen’s music. I bought his big boxed set of Nielsen orchestral works on LP. These EMI recordings were made with the Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra between 1973 and 1976. The recordings were later issued on CD (review ~ review) though they may not still be available. Possibly because I couldn’t afford duplicate sets in those days, I didn’t acquire the EMI recordings on CD; instead, I gravitated to Blomstedt’s Decca cycle, made in San Francisco, which is still available. Writing of the Decca set, Rob Barnett described Blomstedt’s accounts of the Fourth and Fifth symphonies as the “paramount performances” in the second cycle (review); I wouldn’t disagree, though I rate his San Franciso ‘Sinfonia Espansiva’ highly as well.

I hesitate to say that Blomstedt is more animated in the symphony performance; he may have been equally so during the concerto but, of course, the primary focus of the cameras was on the soloist. There’s no doubt of the veteran conductor’s engagement with the Nielsen; you can see it – and you can also hear it. After the leisurely traversal of the first movement of the Brahms I was slightly apprehensive about the symphony but any such concerns were groundless. I think it’s also worth speculating how familiar the VPO will have been with the Nielsen; nowhere near as familiar as they are with Brahms, I’m certain. Yet Blomstedt leads them in an entirely convincing and highly committed account of the Danish composer’s masterpiece.

Excellent tension is established from the very start of the symphony. As the movement unfolded, I was conscious of the attention to detail, not least in the precision of accents; Blomstedt is clearly right on top of the proceedings, guiding and directing with a little gesture here or a meaningful glance there. When the Adagio non troppo is reached, Blomstedt achieves the ideal balance implied by that tempo marking: the music is allowed plenty of space to make its effect – the long, singing lines are played marvellously by the VPO strings – yet he keeps the music moving forward with purpose. The tension is racked up until the side drummer manically tries to disrupt the music. With the VPO in full, sonorous cry there’s little danger of the drummer prevailing and eventually, as the life-affirming climax subsides, he retreats off stage to make a couple of distant final contributions during the eloquently delivered final ruminations by the principal clarinet.

The second movement erupts, full of energy. The performance is very dynamic; Blomstedt makes it so by again ensuring that every accent is pointedly observed. The first of the two fugues (the ‘skipping’ fugue) is strongly defined and by its end the brass are a mighty collective presence. The slower fugue, which follows hot on the heels of its predecessor, is articulated with great care; you can see Blomstedt taking pains over every strand. The last few minutes of the performance are electrifying; the VPO plays magnificently and it’s small wonder that at the end their conductor is so pleased.

Though the Brahms was a bit disappointing, this account of the Nielsen is just the sort of distinguished performance I hoped to see and hear.

The performances are relayed in excellent sound. The picture quality is also very good though the direction of the Brahms is rather too focussed on the soloist – though I suppose that’s inevitable. We get to see much more of the conductor and orchestra during the symphony. One thing which struck me is how cramped the platform of the Goldener Saal appears to be.

Herbert Blomstedt’s durability is something of a miracle – one of my colleagues has a ticket to see him conduct the Philharmonia in Mahler’s Ninth in November; envy doesn’t begin to describe my feelings, though at least I have the consolation prize of his fine 2018 CD recording (review). This DVD is a welcome opportunity to see him still on top of his game in Nielsen’s Fifth.

John Quinn

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.

Technical details

Region Code 0 (Worldwide)

Picture Format: NTSC 16:9

Sound Format: PCM Stereo, DTS 5.1