Déjà Review: this review was first published in September 2005 and the recording is still available.

Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901)

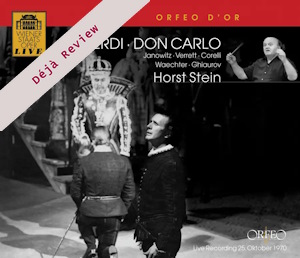

Don Carlo (Four-act version, 1884)

Nicolai Ghiaurov (bass) – Filippo II; Franco Corelli (tenor) – Don Carlo; Eberhard Waechter (baritone) – Rodrigo; Martti Talvela (bass) – Il Grande inquisitore; Tugomir Franc (bass) – Un frate; Gundula Janowitz (soprano) – Elisabetta; Shirley Verrett (mezzo) – Eboli; Edita Gruberova (soprano) – Tebaldo; Ewald Aichberger (tenor) – Il conte di Lerma; Judith Blegen (soprano) – La voce dal Cielo

Chorus and Orchestra from the Vienna State Opera/Horst Stein

rec. live, 25 October 1970, Österreichischer Rundfunk, Vienna, Austria

Orfeo C649053D [3 CDs: 169]

In his long booklet essay Peter Blaha relates the circumstances surrounding the premiere of this staging of Don Carlo. Obviously there were influential factions in the audience who strongly disliked the choice of conductor. German Horst Stein was no unknown quantity in the house; he had conducted there since 1963 but only in repertory performances. Now he was being entrusted a premiere – and an Italian work at that. After the performance he was greeted with “a torrent of boos” as Volksstimme put it. Hearing the performance, which has only recently been dug out from the archives of the Austrian Radio, it is hard to understand this reaction. He may not reveal hitherto unknown depths in this marvellous music but he has a firm grip on the proceedings. He understands Verdi’s intentions and from the start creates the somewhat autumnal atmosphere that runs through the score. Listen to the horn melody of the prelude, so finely executed, which functions as an aural backdrop to the scene that follows. Very often, at the more lyrical passages, he holds back and scales down, as if he wants to say: “Listen to the beauty of the scoring and the melody!” The prelude to Filippo’s great monologue (CD2 track 7) is a moving example, very restrained with a wonderful soft cello solo, but the agitation within Filippo is there as an undercurrent, leaving us in no doubt that this is not an idyllic episode. So far from being an over-genial performance the tragedy and the drama are always in the forefront and time and again Stein underlines and punctuates important lines. He is very well served by the choral and orchestral forces of the Vienna State Opera in as well-balanced a recording as is possible from a staged performance. On sonic grounds it can be safely recommended as being more or less on a par with studio efforts from the same period. What can let it down for some listeners is the unavoidable presence of stage noises, but they are seldom very irritating. Due to movements around the stage the soloists can vary in presence but in the main that isn’t a great problem either. So far so good, then. And when it comes to the solo singing there can be hardly any reservations at all. I will come back to the singing within a paragraph or so, but first a few words about the opera itself.

Don Carlo (or Don Carlos as it then was) was written in French in five acts and first performed in Paris in 1867. Seventeen years later Verdi revised the work for Milan, reduced it to four acts by cutting the first act, removing the ballet music and also revising some passages. It was also translated into Italian. This is the version, more or less, that was used for this Vienna production. In 1886 Verdi also prepared a five-act version in Italian, but it was not until the late 1950s that this version was regularly performed. The original French version also appears now and then (Pappano in Paris 1996, also recorded) and most recently Vienna State Opera in 2004, conducted by Bertrand de Billy, so complete that it contains music that not even Verdi heard (recorded on Orfeo C 648 054 L). Listening to the present recording with the five-act libretto (Orfeo don’t provide the texts) I noted a cut in the last act duet between Elisabetta and Carlo. The finale is performed in the version revised for Vienna in 1932 (obviously not by Verdi) which simply cuts the final pages so that the ghost of Charles V never appears, robbing the opera of something of its mystery.

Accepting these edits one can comfortably sit back and enjoy one of the most formidably sung performances imaginable. Reading the cast list shows that even the smallest parts were given to world stars in the making. So the voice from Heaven is the very young Judith Blegen and Tebaldo is sung by Edita Gruberova, still singing at the State Opera 35 years later. There is also an impressive trio of basses, the same three actually who sang these parts on Solti’s recording made a few years earlier. Tugomir Franc, whom I first encountered as a characterful Ferrando on a Concert Hall recording of Il trovatore in the mid-sixties, is a sonorous and rather youthful Friar. Nicolai Ghiaurov, although Bulgarian is probably the best “Italian” bass since Pinza and has rarely been better. He sings his big monologue with ravishing beauty and deep feeling. It is almost excessively slow but the tension never slackens, thanks to both Ghiaurov and Stein. Elsewhere Ghiaurov is just as good. He is noble of voice in the duet with Rodrigo in the first act and sings gloriously in the third act scene with Elisabetta. Before that, in the scene with the Grande Inquisitore, we are vouchsafed the most spine-chilling mental combat between giants. The world’s two greatest basses here inspire each other to surpass themselves vocally and interpretatively. Martti Talvela, enormous both physically and voice-wise, is the most dangerous Inquisitore imaginable, grand of tone, younger-sounding and so even more of a threat than usual, growling, snarling, hissing. No wonder that Filippo’s words when the Inquisitore leaves: Dunque il trono piegar dovrà sempre all’altare! (So the throne must always bow to the altar!) are more horrified than ever. This scene, miraculous as music-drama in itself, is reason enough to own the set.

Eberhard Waechter, who had a long and important career and became co-director of the Vienna State Opera until his death in 1992, was a lively actor and had a great voice. He may not be ideally Italianate but he portrays an idealistic hothead, simmering with suppressed anger at injustices, occasionally being over-emphatic but in the main singing gloriously. His act 3 aria Per me giunto and the following death scene (CD3 tracks 2-3) are very moving.

In the title role we hear Franco Corelli in what turned out to be his last production at the Vienna State Opera. He displays his well-known vices and virtues: occasionally scooping up to notes and sometimes making show-pieces of his numbers by demonstrating his ability to make those marvellous diminuendos. He is also intense and dramatic and the sheer glory of his voice is often something to revel in. In the first act duet with Elisabetta he sings with great feeling (CD1 track 9). The last act duet, or what is left of it, also offers much sensitive singing.

On the distaff side Shirley Verrett makes a tremendous Princess Eboli, having recorded the five-act version with Giulini for EMI just two months earlier. Here, under live conditions, there is an even deeper identification. She sings a magnificent O don fatale (CD2 track 12), to my mind surpassing every other recorded version I have heard. It is indeed, as Peter Blaha says in his notes, “one of the mysteries of the city’s operatic life that after this initial run of eight performances, she never returned to the State Opera”. And Gundula Janowitz, to the record buying public and on international stages mostly known for her Mozart, Wagner and Strauss, sang a range of Italian roles in Vienna. Her Elisabetta also goes to the top of the list. She sings seamlessly long lines and is in total control of her beautiful voice. Her pianissimos are ravishing but she also shines through the orchestral web in gleaming fortes. I have always held Caballé’s Tu che la vanità on the Giulini set to be the touch-stone recording but now I will probably turn to Janowitz’s version just as often (CD3 track 5).

I hope my enthusiasm for this set shines through. To sum things up I would go as far as to say that this is probably one of the most important “historical” issues from a not so distant past. Not only die-hard Verdians but all serious opera lovers should give it a try, irrespective of how many versions of this ever fascinating opera they already have. The Giulini set, at present in the “Great Recordings of the Century” series on EMI Classics, is of course hors concours, but the singing on this Orfeo set is on the same level and in several instances even better.

Göran Forsling

(This was Ralph Moore’s top recommendation in his survey for a recording of the four act, live, Italian version.)

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free